One of the benefits of working in old buildings is that they often conceal secrets that are just waiting to be discovered. Before joining the V&A, I used to work at St Paul’s Cathedral, one of the world’s most iconic buildings and filled with glorious art. In the Cathedral’s crypt, I found a fascinating object displayed under a glass – a workman’s cap from the 17th century, which someone had found in the roof space in 1928. The cap was a hugely personal object and reminded me that hundreds of years ago a real, living person had helped build or looked after the very same building that I was now restoring. It wasn’t long before I was making interesting discoveries myself that would give me further clues about the people who had built the place. When I was working high up on a scaffolding, far away from anyone’s view, I found signs and symbols on the stonework left by ancient stonemasons. However, my most interesting discovery happened while repairing the pointing on the masonry. Tucked between the blocks of stones, I found huge amount of ancient oyster shells. I was told that oysters and beer were a common diet in 17th century London and the stonemasons had found a good use for their leftover lunch by inserting the shells with mortar into the gaps between the stones, although there may also be a technical reason why the addition of shells is a good idea. I must confess that these tangible discoveries brought me closer to the real 17th century craftsmen and draughtsmen than any of their creations.

The V&A may not be as old as St Paul’s Cathedral, but it is certainly a great treasure trove for someone who is interested in finding mysterious bits of evidence left by people from the past. Every so often, my colleagues and I stumble on the most peculiar items hidden inside some of the objects we work on.

These discoveries are similar to the ‘time capsules’ I found at St Paul’s and they take us into different periods in the museum’s past. They may be signatures or scribbles usually written somewhere on the supports at the backs of objects or inside pedestals by the people who built them. Or they may be items that have been lost or deliberately stashed inside a monument during its creation. Nevertheless, what links these finds is that they were left by those unknown or long-forgotten people who worked in the museum long time ago, the craftsmen who looked after the building and its contents and constructed the monuments and mounts that support them. For us, the conservators and technicians, it is hugely exciting to find traces of our predecessors, as we are often unable to find record of them in our files. This is because it was fairly uncommon, until recent years, to record treatments or write down the names of the craftsmen who looked after the objects. It is interesting that these people knew that they would be forgotten and therefore they secretly hid reminders of their existence, in a hope that one day someone would discover them. Subsequently, as we have been working on major renovation projects in many of the museum’s galleries, we have been slowly able to discover these hidden treasures – insights in to a pocket of life that existed before any of us got here.

Discoveries made in the British Sculpture Galleries and the Medieval and Renaissance galleries

Between 2005 and 2009 we worked on two large parallel projects creating the Dorothy and Michael Hintze Galleries and the Medieval and Renaissance galleries. We were required to transfer large monuments and other sculptural objects from various gallery spaces in order to display them in a more suitable areas and arrangements as part of the Museum’s Future Plan. We dismantled numerous large monuments and rebuilt them in the newly refurbished gallery spaces. As you can imagine, this was an extremely complicated and laborious task and took years to accomplish. However, despite the heavy work it was hugely interesting to learn how the monuments had been constructed in the past.

As we were taking apart some of the larger monuments, we occasionally discovered interesting articles at the back of them. Amongst the mix of cement, mortar and odd bits of chicken wire, we occasionally found old newspapers tucked amongst the rubble. These newspapers and materials gave us clues about the dates that different galleries had been installed in the past.

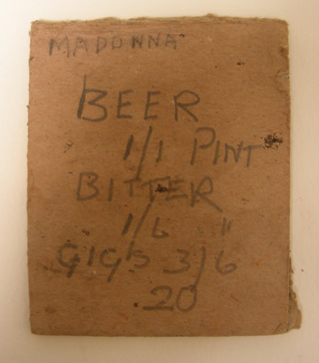

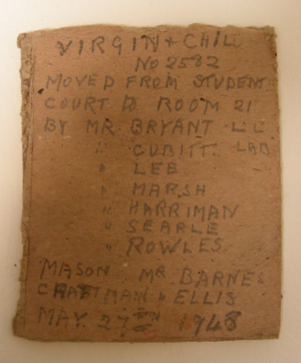

We discovered that a major refurbishment in the present Dorothy and Michael Hintze Galleries could be dated to the late forties thanks to a note that we found, which was signed by the mason Mr O Barnes and the craftsman Mr Ellis on 27th May 1948. The note was found behind the Misericordia relief which was attached to the brick wall in several sections with cement, plaster, hessian and loose bricks. The object is displayed today in the Paul and Jill Ruddock gallery adjacent to the main entrance.

We found that monuments that had been installed in the 1960s had vast amounts of cement, which seems then to have been a popular material to use. As we were carefully trying to release the monuments from their cement and brick backings we occasionally found interesting bits of debris tucked inside. While we were taking apart a 17th century alabaster and marble tomb monument dedicated to Sir Moyle and his wife Lady Elizabeth Finch, deep inside the structure we discovered, among the debris of old cigarette stubs, cigarette papers and sweet wrappers a message in a bottle.

The message was an old time sheet, which had been scrolled inside a bottle of Pepsi. The piece of paper did not say how much the person would have had earned, but it gave us valuable information about the the company that had been commissioned to install the monument. The sheet was signed by Mr Grealish who had been employed by J. Whitehead & Sons. Ltd who were based in Kennington, Oval. Curious to learn more about the company I found a mention of them on a website called Mapping the Practise and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851-1951. Apparently J. Whitehead & Sons. Ltd were a multi-generational firm of funerary sculptors, undertakers and marble merchants who specialised in a variety of services including Church restorations. The company was active from 1880 until 1985.

We also found an old torn up bag of mortar and rendering mix, which gave us useful information about the material the brick core was constructed with.

What did we do with all this material?

As we were bringing more and more of these wonderful items in our studio we had to sort out a place to store them. We took photographic record of the finds, filed the most significant items in our conservation records and placed some off the items back inside the monuments.

In my next post I’ll tell you about more interesting finds including a secret parcel.

Very interesting piece . Now waiting to learn about secret parcel!

Jut loved reading this! Thank you for sharing your experiences. I wish I could say that I had worked at such significant and wonderful places – you’re very fortunate :)

I hope that you left your own notes as you reconstructed the monuments! But I’ll understand if you don’t tell us.

According to me this post is really valuable post which change your views.