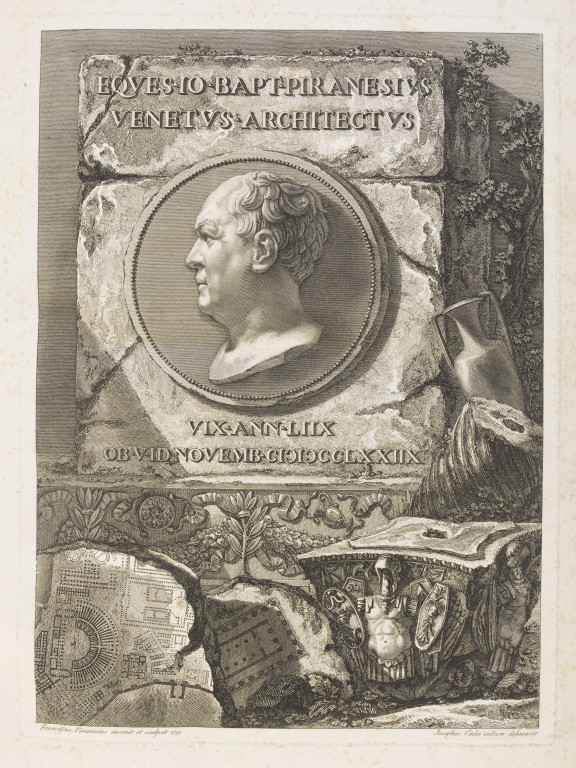

In the late-18th and early-19th centuries, increased travel and archaeological discoveries, at sites such as Pompeii and Herculaneum in Italy, led to a revival of interest in ancient and classical decoration. The work of architect and printmaker Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) helped to pioneer this rediscovery of Roman remains and he was one of the leading figures in the development of the Neoclassical style.

Piranesi is regarded by many as one of the greatest Italian printmakers of the 18th century. He produced a vast amount of work in his lifetime, with an obvious enthusiasm for creating intricate, detailed images and designs. One of his early biographers reported him as saying:

“I need to produce great ideas, and I believe that if I were commissioned to design a new universe, I would be mad enough to undertake it.”

Venetian by birth, Piranesi was the son of a mason and master builder and had a wide ranging training in architecture, stage design and perspective composition. He settled in Rome in 1740 and came to establish himself as a well-known figure, producing a vast number of etchings illustrating Roman architecture and antiquities and designing replica Roman objects for the Grand Tour tourist trade. However, Piranesi did not limit himself to simply recording and replicating designs, his imagination and creativity also led him to break conventional rules of design and he became equally renowned for his images of fictitious monuments and architecture.

Piranesi is well-represented in the V&A’s Prints collection and I am pleased to say that this key print will be featuring in the Europe Galleries, as part of our display on Neoclassicism.

The print is from a series of etchings Piranesi made whilst documenting antiquities excavated in Italy in the 18th century. It shows a Greek marble vase decorated with bas-reliefs, known as the ‘Medici Vase’ (which is now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence). The vase is believed to have been made about AD 50 to 100 and shows in carved relief the sacrifice of Iphigenia, daughter of Agamemnon, King of Mycenae. Iphigenia is flanked by the figures of Ulysses and Agamemnon.

The printing plates Piranesi produced included text with information on the circumstances of discovery of each object and their contemporary location. They also bore dedications to Piranesi’s patrons and influential friends. This particular etching was dedicated to His Excellency, Signor General Schouvaloff, the Russian connoisseur, although unfortunately the text is missing from this example.

The Medici Vase is known to have been at the Villa Medici in Rome by 1598, first appearing in the inventory of the Medici collection that century. Its design was widely copied, and appeared in many prints throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.

Piranesi’s etching of the Medici Vase is one of a number he made between 1768 and 1778 that were issued as separate plates. However, in 1778 they were assembled and published as a collection in two volumes under the title Vasi, Candelabri, Cippi, Sarcofagi, Tripodi, Lucerne Ed Ornamenti Antichi. Alongside Piranesi’s other publications, this series of prints served as source material for many architects and designers and had a major influence on the development of Neoclassical style.

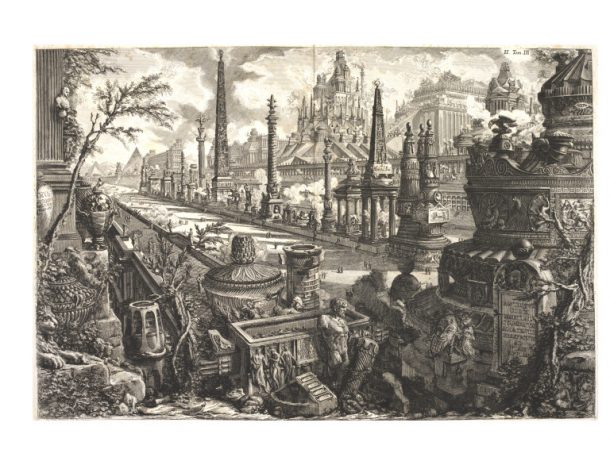

Piranesi produced the two engravings below for Le Antichita Romane di Giambatista Piranesi (also known as Le Antichita Romano) which was first published in 1756. A testament to the longevity of Piranesi’s influence is the fact that they come from a volume in the V&A’s collection which was bound and published in Paris around fifty years later, between 1803-1807. I think that together they clearly demonstrate both his keen eye for practical architectural detail and understanding of construction and his enthusiastic creation of ‘antiquity fantasties’

This first engraving shows a view of the Walls of Aurelian in Rome, focusing on the aspect of the wall facing into the city, depicting the arches and periodic towers. At the bottom of the walls is debris from the ruined walls. Different aspects of the walls are explained through a key, letters A, B, C, D, and E, which Italian script explains at the bottom.

The double-page engraving below depicts an imaginary vision of the Appian Way, showing each building as whole, not ruined. The Appian Way is lined with many columns and statues, with tombs in the background and pyramids visible in the distance. In the foreground a detailed collection of antiquities, including sarcophagi, engraved slabs and burial urns are shown.

Piranesi also produced designs for interiors, many of which show creative re-appropriation and combinations of classical motifs and design elements. The etching below shows a highly decorated chimneypiece, from a set called Diverse Maniere d’Adornare I Cammini. The design incorporates human figures, lions, grotesque ornament, candelabra and Egyptian figures. Two chairs on either side are also covered in decoration, with horses leaping from the back of the seat, and animal legs as supports.

Factum Arte made this incredible animation of the virtual modelling of another fireplace design by Piranesi for The arts of Piranesi at the Foundazione Giorgio Cini about four years ago.

As well as being a skilled architect, designer and printmaker, Piranesi also ran a thriving business producing ‘ancient’ sculptures and vases which he sold to foreigners visiting Rome. This vase, based on a Roman funerary urn, is one of several produced by Piranesi’s workshop, probably during the 1770s. With its combination of classical foliate motifs and its elegant classical shape, it would likely have appealed to European visitors to Rome.

Looking through the Museum’s collections, Piranesi’s lasting influence can still be found in the work of contemporary artists and printmakers.

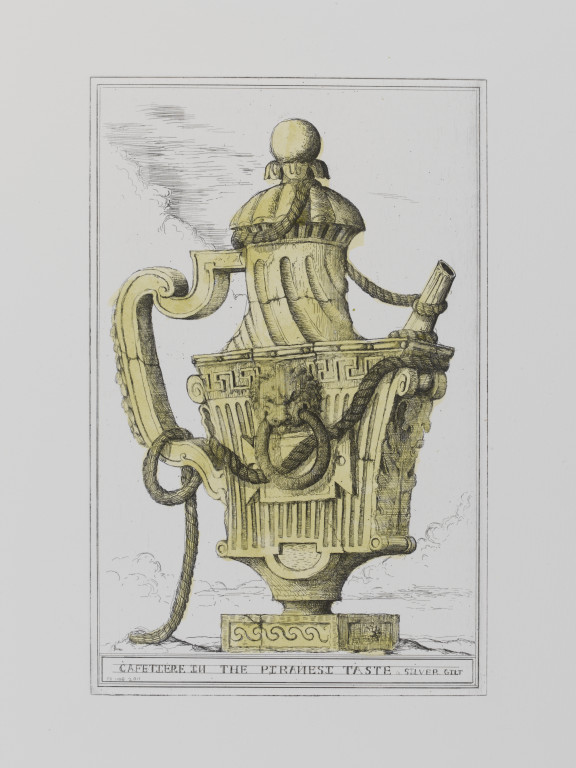

Piranesi is directly referenced in Pablo Bronstein’s print of a fanciful coffee pot as a building within a landscape, which offers a playful treatment of scale and a reflection of social hierarchies represented through objects.

Anne Desmet’s 2005 work Whirlpool is one of a series inspired by the architecture of Rome. It is formed by a seashell, with a wood-engraved image of a circular architectural structure (like a Roman amphitheatre) and a fragment from an Italian banknote collaged on the inner surface. There are allusions to Piranesi both in the subject matter, and in her acknowledged debt to her study of his engraving techniques.

If this has whetted your appetite for delving more into the work of Piranesi, I thoroughly recommend taking a look through Factum Arte’s website which provides a lot of detail about their making of pieces for Diverse Maniere: Piranesi, Fantasy and Excess, an exhibition that took place at the John Soane Museum (London) earlier this year. The exhibition looked at the relationship between Sir John Soane and Piranesi and included a group of physical objects produced from designs by Piranesi that were never realised during his life.

I’ve particularly enjoyed this wonderful animation of Piranesi’s Carceri d’Invenzione series, made by Gregoire Dupond at Factum Arte, which allows you to ‘take a wander’ through some of Piranesi’s early imagined environments. Piranesi etched this rather captivating series of sixteen visionary images in his late twenties and they clearly demonstrate his creative imagination, architectural ambitions, obsessive interest in antiquity and skill as a printmaker.