Meeting once again in the Europe Galleries on the 10th February, our esteemed guests were challenged with the task of flipping their perspective on the history of Europe, and looking at it from the outside in, under February’s Salon theme: ‘Europe through non-European Eyes’. Our three speakers were José Ramón Marcaida (CRASSH at the University of Cambridge), Anna Grasskamp (Cluster of Excellence at Heidelberg University), and Daniela Bleichmar (Art History and History Departments, University of Southern California).

In the galleries themselves, the room that most closely illustrates this theme is Room 7: ‘Europe and the World’. I think that this room is one of the most unexpected and therefore one of the most interesting in the galleries, because it brings to prominence that which usually remains unstated and hidden in museum displays: a wider provenance of the objects.

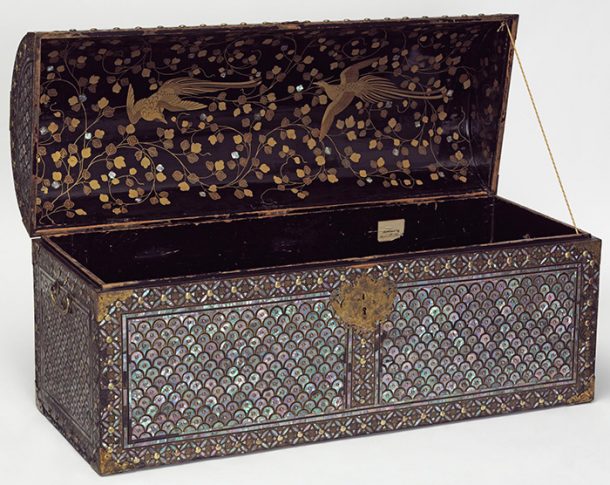

The objects in this room demonstrate the flourishing networks of trade and colonisation being formed throughout the world in the 17th and 18th centuries. A good example is the Japanese coffer, with its beautiful inlaid shell decoration. Japanese lacquer work was in high demand in Europe during the 17th century and eventually led to the style being copied by European craftsmen and sold to a wider consumer market. The European version of the technique was called japanning as a result, similar to the use of china for porcelain made to replicate Chinese originals.

Typically however museum exhibitions do not draw attention to these kinds of connections, unless they have a special significance. The reason for this was suggested in the Salon: quite simply, the space for text in displays is so limited that curators cannot list the extensive – and often exhaustive – list of provenances for the materials, makers, uses, etc. The list could be endless.

I would like to focus in on Anna Grasskamp’s opening presentation, which highlighted two excellent examples of a similar style that can also be seen in the Europe Galleries. They demonstrate the combining of European and Asian designs, which Anna called, ‘Euraserie’ – a play on the more familiar, ‘Chinoiserie’ – and demonstrated how the increase in global trade and the migration of regional tastes during the 17th and 18th centuries was not a one-way system.

The first example she used was the little figure of a European merchant, housed in a Chinese lacquered box. The dichotomy of the European appearance of the man and the evident Chinese craftsmanship would have been an excellent conversation piece in the country house it was made to be displayed in. Anna however, argued that this was a piece from Guangzhou (also known as Canton), which was known for producing wares consumed by Asian, as well as European courts. European figures were preferred by Asian markets too. The emperor Chien-lung (1711-1799) was known to use European objects as tools to stage his power, including figurines of European ladies.

Anna’s second example was the blue and white kraak ware porcelain, made in China for Dutch export and commonly seen in Dutch paintings of the period. The mass production of this kind of porcelain and the increase in trade facilitated by the new Dutch trading post in Taiwan in 1625, ensured the European market was well-catered for. But, in a scenario that challenges our conventional historical chronologies, pieces of the kraak ware were found in the tombs of the Chinese elite, demonstrating once again that the taste for this style was not limited to Europe.

The question Anna closed with and posed to the rest of the Salon guests was: ‘How can we stop simplifying readings of Eurasian objects through new systems of scholarship and through collaborations with other museums?’

You can listen to the responses to Anna’s question, along with Jose Ramon Marceida and Daniela Bleichmar’s approaches to the same theme in the podcast below. We can look forward to the fourth and final Salon in the ‘What Was Europe?’ series on the 9th March, 2016: ‘Ephemeral Europe’.

It´s a beautiful