A little late for Valentine’s Day, but perhaps of interest to those looking to ‘play the long game’; the object that has taken my fancy today purports to have some wisdom to impart on that tricky subject of love …

It can be found in Gallery 5 (The rise of France) as part of the Parisian Interiors display, which considers the interior decoration and objects associated with ‘elegant living’ in France.

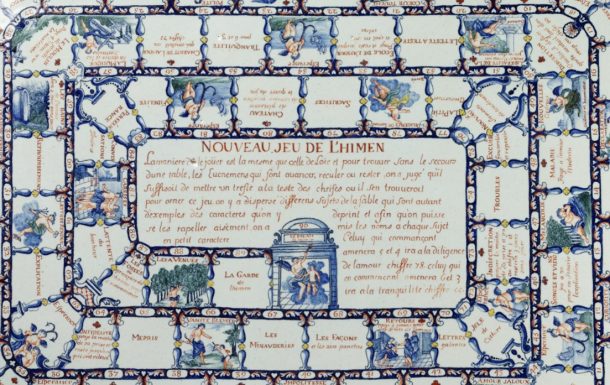

Made in Rouen around 1725-1735, it is a large tray made of fine tin-glazed earthenware (conventionally referred to as ‘faïence’ in English).

As you might expect, this tray would have served as a ‘cabaret’ for a tea-set (like the example below). However, this particular tray has an additional contribution to make to social engagements – by also serving as a board-game. Interestingly, in French, board-games are often called ‘Jeux de Societé’ – clearly putting an emphasis on the social nature of the experience. Games were often intended to be both entertaining and educational.

Waddesdon Manor curator Rachel Jacobs has noted that: ‘In the Dictionnaire des Jeu, (1792) Jacques Lacombe attributed the rise of game playing to the court of Louis XIV, claiming that games spread from the courts to the cities and onto the provinces, soon all seemed to be playing, men, women and children alike.’ (‘Playing, Learning, Flirting: Printed Board Games from 18th Century France’)

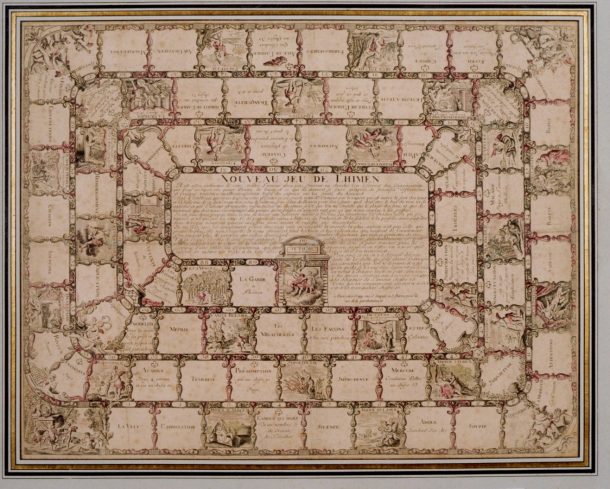

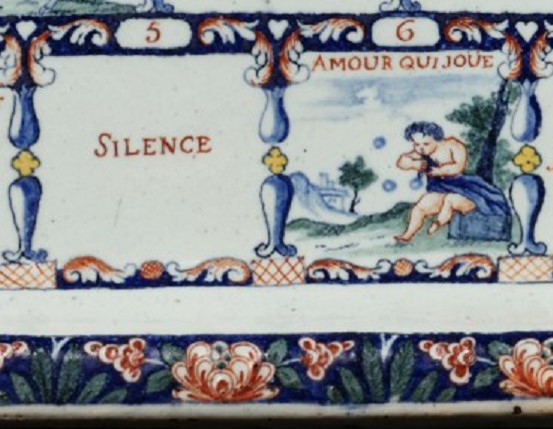

The game on this tray is a variant of the ‘jeu de l’oie’, known in English as the Game of the Goose, similar to today’s Snakes and Ladders. It is a 90-square, race game in a spiral layout that would have been played with dice and tokens.

The title ‘Nouveau Jeu De L’Himen’ may initially conjure up rather startling anatomical suggestions today, but ‘himen’ here is actually referring to Hymen the ancient Greek god of marriage ceremonies (also known as Hymenaios or Hymenaeus).

Hymen is sometimes found depicted as a woman (see left), due to a later story, in which he disguised himself as a woman in order to join a women-only religious procession that the woman he loved was attending.

The players of this game race to reach the winning square, the Palace of Hymen.

The numbered squares are inscribed with stages of the game and illustrated with various figures from Greek and Roman mythology, including: Psyche, Vertumnus, Pomona, Médon, Venus, Adonis, Medea, Pan, Mercury, Cephalus, Procris, Cadmus, Hermione, Danae, Apollo, Ulysees, Penelope, Boreas, Galatea and Pygmalion. These classical references would have been instantly recognisable to the educated elite of the time as texts such as Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Homer’s Odyssey were considered essential reading from a young age.

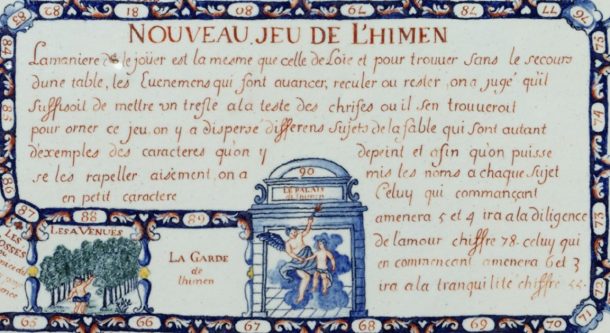

In the centre of the tray, the rules to this game of love/marriage are provided.

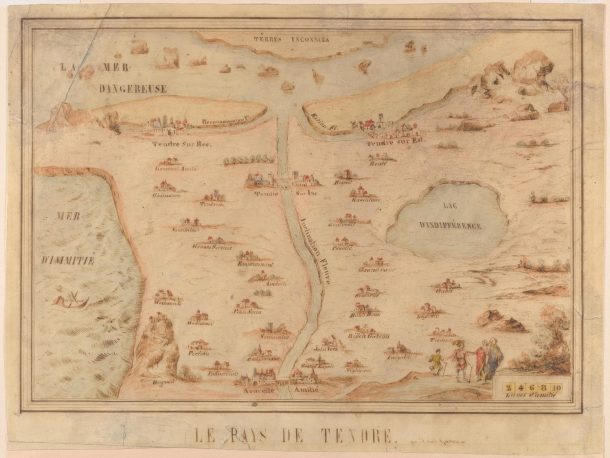

The game is played according to principles established by Madeleine de Scudéry in the Carte du Tendre that was included in the second volume of her 1654-61 novel Clélie. The Carte du Tendre was a topographical and allegorical representation of the path to love (through conduct and practice) according to the précieuses of the day. However, it has been noted that this board-game differs from the Carte du Tendre’s ideals of love by prioritising practicalities such as finance.

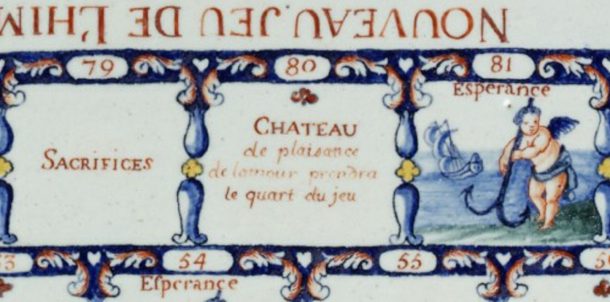

Rather than offer serious reflections on the subject of marriage, the game mainly highlights the role of chance in relationships and ‘achieving’ happiness. As you negotiate your way to the Palace of Hymen, there are a number of helpful/positive and hazardous/punishing spaces to encounter on the board. For example, ‘discretion’, which is said to be ‘so desirable a quality’, whooshes your forward an additional 30 spaces to the ‘Chateau de Plaisance de l’Amour’ (Chateau of the Pleasure of Love).

Correspondingly, ‘indiscretion’ receives the worst punishment, as you get sent back to the start, lose half your counters and miss three turns. Values such as sacrifice and faithfulness are not deemed worthy of any reward … Indiscretion being deemed worse than infidelity would today likely prompt great discussion over the refreshments being served, I’m sure.

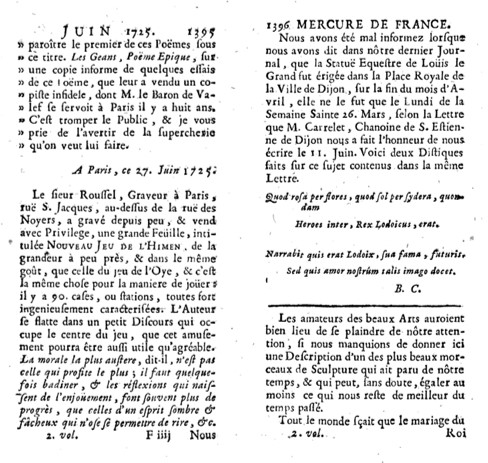

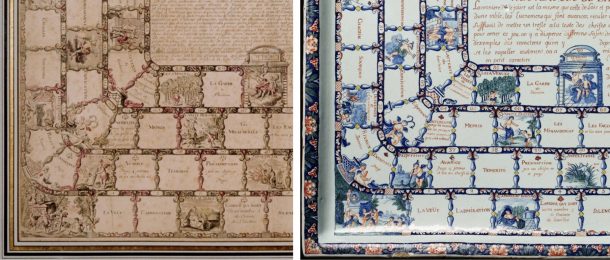

The design on the tray reproduces that of a printed board-game whose publication was announced in the Mercure de France of 27 June, 1725.

It appears that the printed game was initially issued by the Crépy family, in Paris, in 1725 and then later reissued in 1750 (see Henry R. D’Allemagne, in Le Noble Jeu de l’Oie, Paris, 1950).

Another version of the game, with slightly different decorations, issued by Crépy in 1767 has also been found in a private collection.

The decorator of the tray evidently used the earlier engraving. They were faithful to the design and only abbreviated the length of the rules for the game in the centre and a few of the inscriptions for the individual squares that were too long to fit in. The colouring corresponds to the date of the publication and suggests that this tray was made only a short time after the game was published.

The border decoration is composed of stylised flowers and leaves similar to that found on the broderies (embroidery) decoration for which Rouen is famous, inspired by engravings after artists such as Jean Bérain and Daniel Marot. The French faïence potteries benefited greatly from the patronage of nobles and wealthy merchants. By 1720 eight faïenceries were recorded as operating in Rouen.

Faience trays with a number of distinctive types of decoration can be found, including those with coats of arms, maps, rocailles and history painting. I was interested to find some that also served as chequerboards for draughts or chess, although I feel that these don’t have the same sense of social insight and curious entertainment that The Game of Love continues to have for me today.

Is is so something the play game.