Tonight will see Brussels’ Grand Place packed with spectators for the annual Ommegang, a centuries-old traditional procession that takes place every July in Brussels, Belgium. Ommegang means ‘walking around’ in Old Flemish. Ommegangen were originally religious processions in which relics or venerated images were carried around a prescribed route to mark a particular holy day. ‘Ommegang’ came to be a generic term for the various medieval pageants and parades celebrated in the Netherlands and northern France. These were characterised by the combination of religious dedication and the secular participation of guilds, craftsmen and other civic groups. Today’s Brussels Ommegang is now devoid of religious connotations and instead focuses on local heritage and folklore.

The Brussels’ Ommegang tradition was initially a procession (on the Sunday before Pentecost) to commemorate Brussels’ ‘miraculous’ acquisition of a sculpture of the Virgin Mary from Antwerp cathedral in 1348. The procession originally took place under the patronage of the guild of Crossbowmen and the Church of Notre-Dame du Sablon, where the statue was housed. The Ommegang Oppidi Bruxellenis Royal Society’s web page features a useful synopsis of the miracle of the Virgin Mark statue.

Today’s dazzling and colourful Ommegang is an historical evocation of a procession held in 1549 to commemorate Emperor Charles V’s ‘Joyous Entry’ (his first official peaceable visit) into Brussels.In 1549 Charles V, his son Philip, and Duke of Brabant, and his sisters, Eleanor of Austria, Queen of France and Mary of Hungary all watched as representatives from the crafts and trades of the city and others processed through the streets of Brussels and around the Grand Place. Today, the Ommegang Oppidi Bruxellenis Royal Society continue to evoke this centuries-old event, with over 1,400 performers parading through the Grand Place.

Another especially magnificent Ommegang was that of 1615 which was dedicated to Archduchess Isabella (with her husband Albert, the Governor of the Spanish Netherlands) as queen of the Crossbowmen’s Guild. In that year the procession represented the alliance between the Habsburg rulers and the Brussels civic authorities. The Ommegang was mixture of religious parade, courtly celebration, guild procession and carnival entertainment.

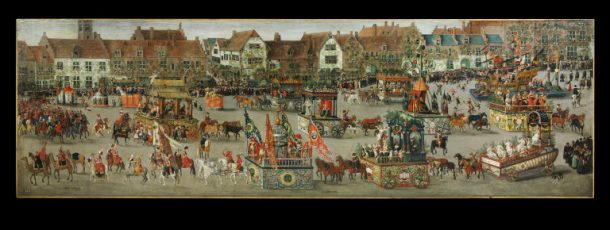

To record the 1615 Ommegang, Isabella commissioned the artist Denys van Alsloot to produce six paintings depicting the entire procession, for 10,000 livres. Van Alsloot was born in Brussels and around 1600 had entered the service of the Archduke Albert and Archduchess Isabella who entrusted him with many important commissions. Flemish painters of the 15th-17th centuries were internationally renowned for their painstakingly exact depiction of contemporary scenes and these works are some of the best known depictions of Netherlandish civic spectacles. One of the star objects in the Europe 1600-1800 Galleries will be this impressive panoramic oil painting from the series.

The paintings are thought to have been at Isabella’s palace in Tervuren by 1619. Only four of the original six survive, two being in the Prado in Madrid and two in the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A 5928-1859 and 168&169-1885). The last of these was divided in half at an unknown date. The V&A’s paintings were bought at different dates in the 19th century (1859 and 1885) having been alienated at some time from the Spanish Royal Collections.

The painting going in to the Europe galleries is one of the most important in the series as it depicts the ten lavish floats which formed the most spectacular element of the procession. This section of the procession begins with the camels in the lower left-hand corner and snakes across the canvas in an S-shape ending in the top right corner.

The floats are decorated to depict a range of subjects including biblical events, allegories of virtues and mythological gods. Several of them pay tribute to Isabella as ruler of the Southern Netherlands while others depict religious events or stories. Each of the floats are fascinating, but my three current favourites are the following:

The first float is that of King Psapho of Lybia, who can be seen seated at the rear of the float. King Psapho was known for teaching his parrot to say ‘Psapho is God’. In acknowledgement of this, inside the cage is a boy dressed in feathers, trying to teach the birds to say ‘Isabella is Queen’. As these birds were apparently doves, painted to look like exotic parrots, the boy probably did not succeed in his task!

The fifth float features the Tree of Jesse, with nine daring individuals perched high up in scooped chairs. The Tree of Jesse is a visual depiction of Christ’s ancestors as a tree growing from Jesse of Bethlehem. The figure at the top holding a baby (quite possibly a real baby!) represents the Virgin Mary and Child and the figures sat at each corner of the float represent the Evangelists.

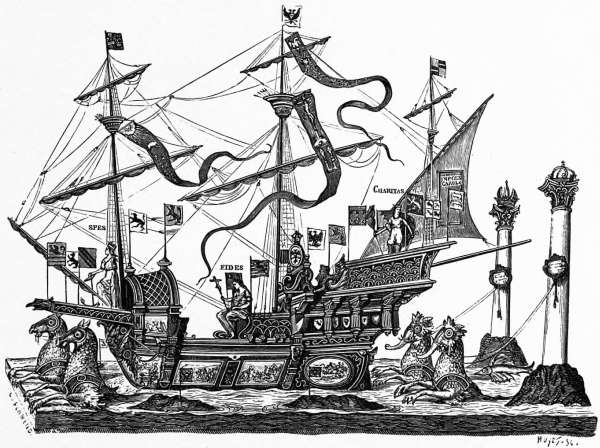

The final float takes the form of a ship drawn by unusual marine monsters. This float was not designed for this parade but was in fact made over fifty years earlier, for a funeral procession held in Brussels for Charles V on 29th December 1558. The vessel was the size of a real ship and was intended to illustrate his maritime greatness.

Marshals didn’t just have to keep an eye on people, they also had to watch for the many animals which featured in the parade. Animals were used as symbols of prestige, power and political propaganda. Both exotic and commonplace animals helped add to the spectacle. Camels in particular would have been a rare sight in 17th-century Europe and therefore increased the sense of it being an extravagant, special occasion. They may have come from a menagerie belonging to Albert and Isabella at their palace just outside Brussels.

Large artificial animals are also shown parading amongst the floats. In the top row of the painting, there are four artificial animals – two camels, a unicorn and a fantastic bird. These would have been made from wickerwork and covered in painted canvas, with additional decorations. Each of the gigantic animals is ridden by a smartly dressed young child.

To get more of a sense of what it would have been like to witness the Ommegang, it is important to consider not just what could be seen but also what would be heard.

Music was an important part of the procession. In amongst the noise of crowds shouting, the clattering of horses’ hooves and caged birds flapping around, music would be heard coming from the various instruments which can be spotted in the painting. An orchestra of Apollo and the Muses is playing on the fourth float. Individuals with horns and bagpipes can also be seen. Bells attached to the reins of the artificial animals would have also added to this busy soundscape.

The sound of spitting sparks would have also been heard as men dressed as demons ran amongst the crowds. The demons’ costumes are based on traditional medieval depictions of devils, which were intended to frighten sinners. The demon shown below holds a device called a ‘fire club’. This would have been made from a hollow reed or a cane filled with a mixture of gunpowder and charcoal. It was designed to burn, rather than explode, emitting a stream of fizzing sparks. Judging by the reactions of spectators, it was rather noisy and not too pleasant to be caught in the path of it.

The modern Ommegang is so popular that it has become a ticketed event, with grandstand seating in the central square. In 1615 spectators would line the route or, if they were lucky enough to live nearby, could watch from upstairs windows.

My favourite aspect of this painting is the amount of detail van Alsloot brings not just to the procession itself but also to the hundreds of onlookers.Van Alsloot’s inclusion of various scenarios and ‘mini-dramas’ within the crowd really animate the scene. They bring both a sense of the excitement the Ommegang created and also tantalising glimpses into citizens’ everyday lives.

I will definitely be looking at footage of this year’s Brussels Ommegang with a keen eye to see what similarities can still be spotted, almost 400 years after Archduchess Isabella was celebrated with such a remarkable spectacle.