Valentine’s Day will soon be winging its way once more into our lives. Shades of pink and red currently fill the shelves of British card shops, stationers and supermarkets. Cards are also popular in many other countries and now of course available in digital format. With all these pre-packaged declarations of love, have you ever stopped to wonder however, how our ancestors expressed their love on 14 February…

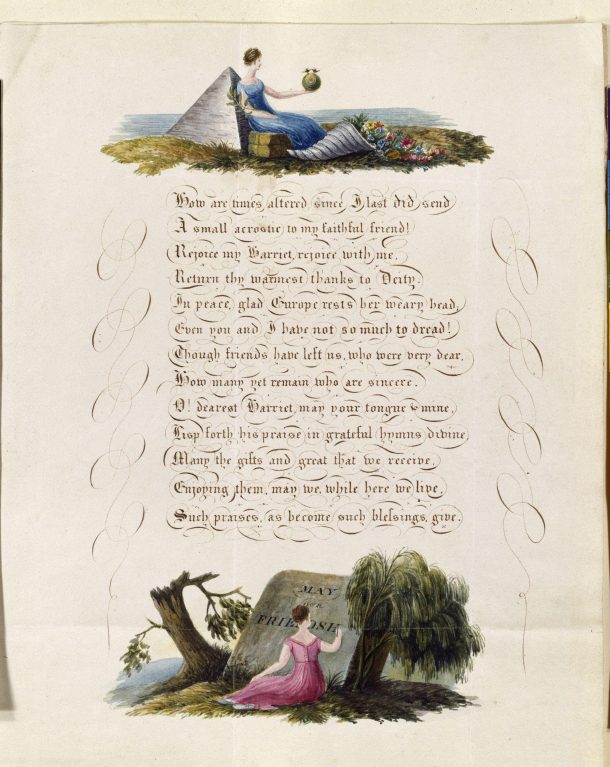

The pre-printed verse in a valentine came after years of carefully handmade cards, with verse written directly by the suitor.

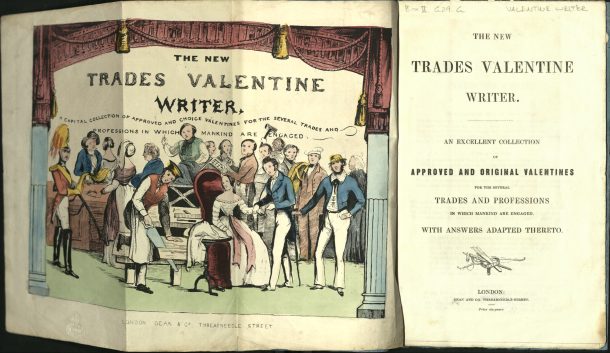

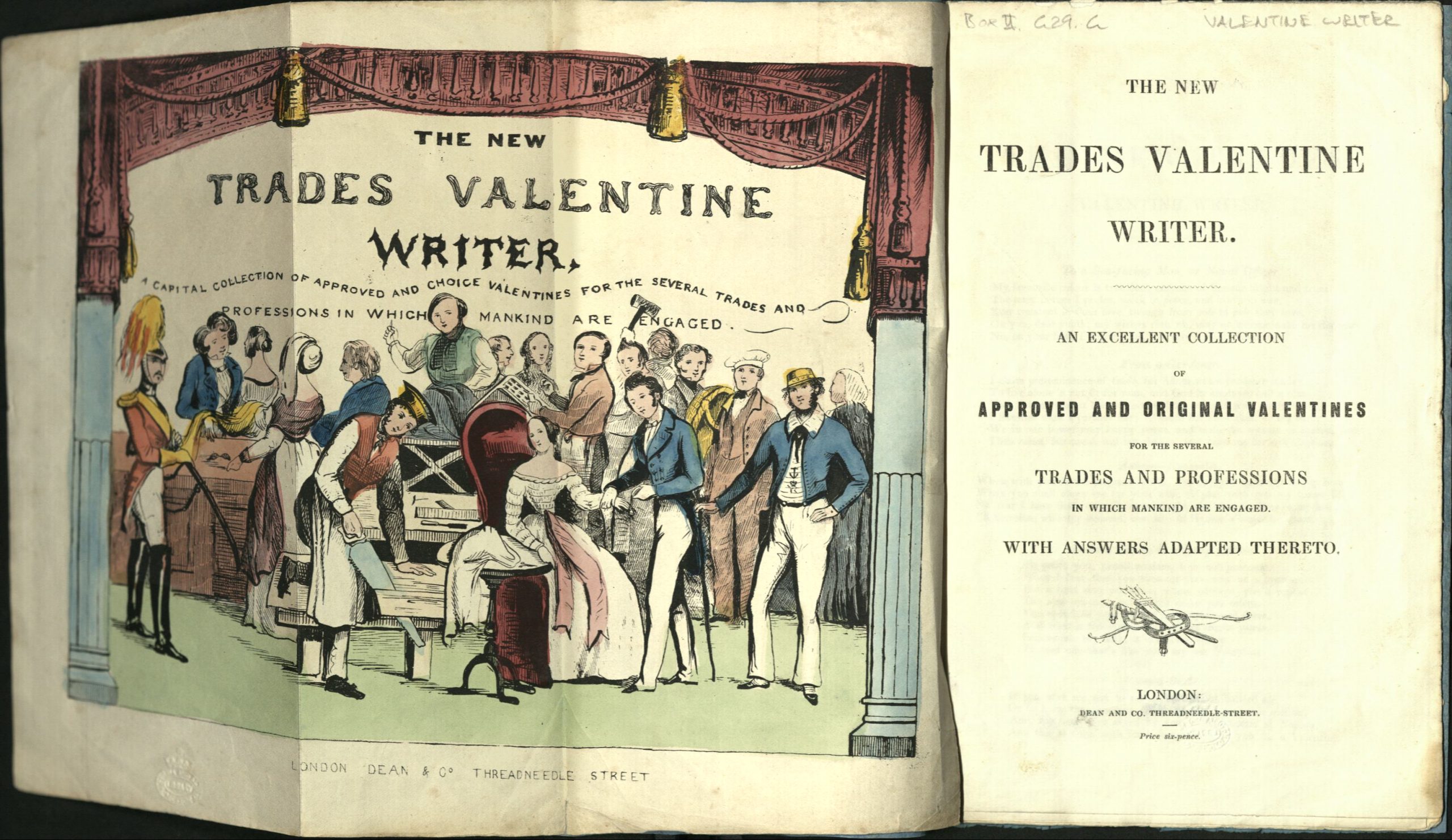

Today there is always a template available for admirers striving to impress, be it printed inside a Valentine’s Day card or easily found through a quick internet search for suitable verse. From the early decades of the 18th century stationers devised their own guides to make the process of composing a valentine as painless as possible. Below, we can see an 1850 valentine writer from the National Art Library collections within the V&A.

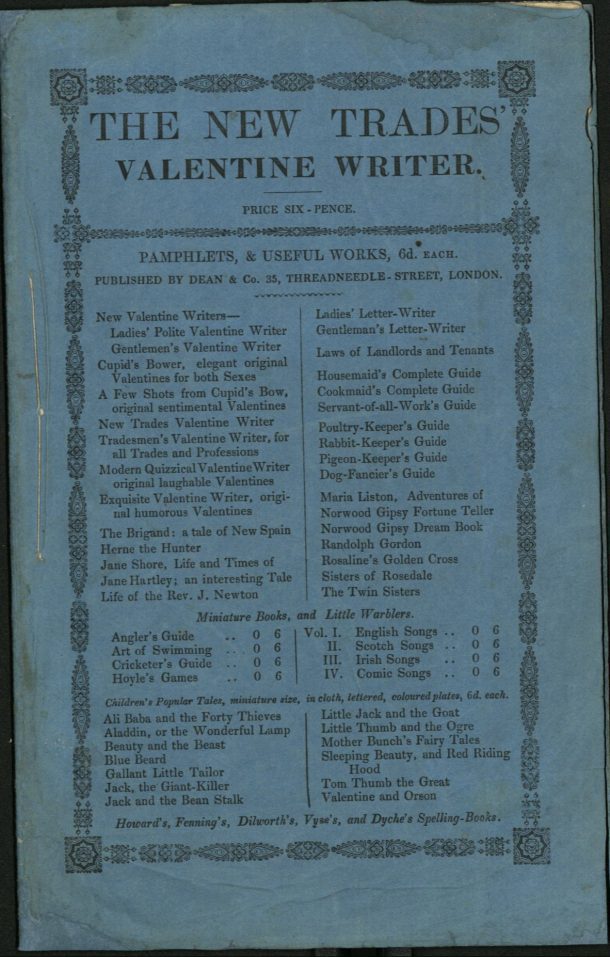

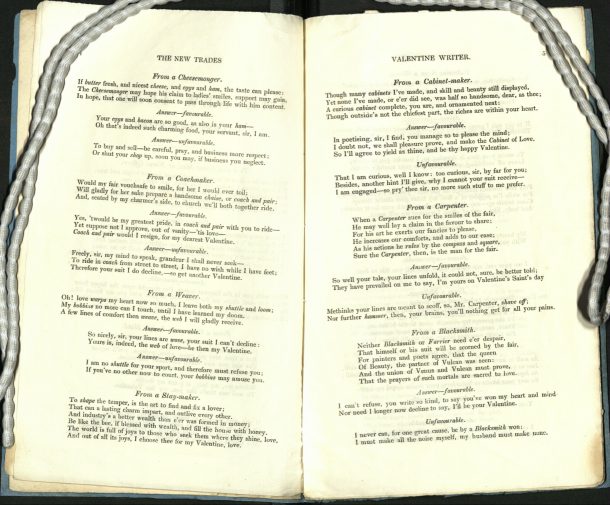

Listed in the left-hand column on the front of the publication is a wide variety of short pamphlets available published in a similar vein. These pamphlets cover all moods of valentine, from the polite to the humorous or quizzical. Within this particular publication the vocation of the composer serves as inspiration for the verse, be they carpenters, cheesemongers or cabinet makers…(& that’s just some of the ‘Cs’!). The verses are mainly crafted for a male writer, with responses provided for the female intended.

The helpful responses given under each rhyme, similarly use imagery and ‘punnery’ linked to the sender’s line of work. See below, for example, suitable verse if you wish to encourage or dissuade the interest shown by your local baker…:

Answer – favourable

Sweet as your cakes is every line, nice as your rolls, my Valentine;

So I’ll consent for life to trust ye, but hope you will never be crusty.

Answer – unfavourable

Your lines, I’m sorry to relate, like your loaves are short of weight:

Besides, I wish that you should know, i ne’er will wed a man of dough.

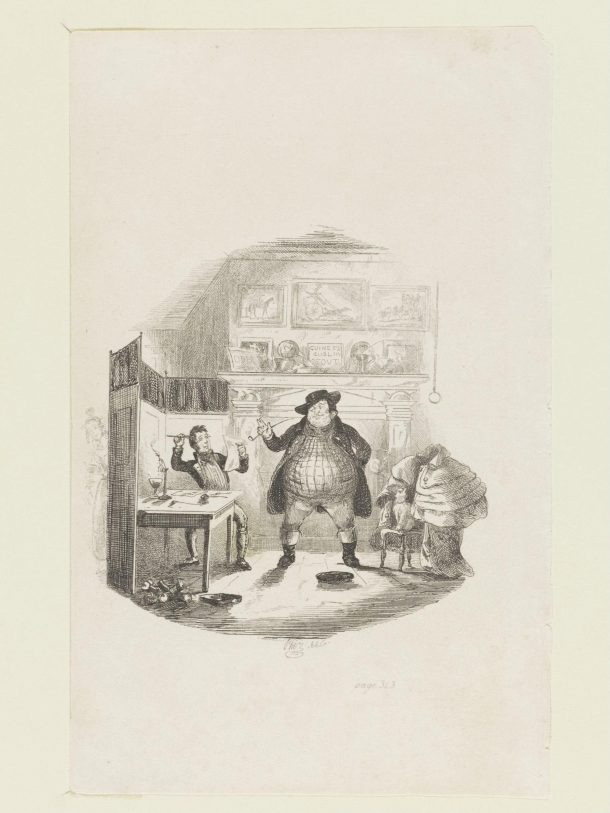

A great example, from a similar time period, of a character trying to compose his own verse can be found in Charles Dickens’ debut novel The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (1837). Pickwick’s valet, Sam Weller requests ‘to be served with a sheet of the best gilt-edged letter-paper, and a hard-nibbed pen which could be warranted not to splutter’, after being reminded of the approaching celebration by a gaudy display at a stationer’s shop in the back streets of central London. He appears to compose his own valentine verse, some of which is approved of by his father as ‘there ain’t no callin’ names in it— no Wenuses, nor nothin’ o’ that kind. Wot’s the good o’ callin’ a young ’ooman a Wenus or a angel, Sammy?’.

The whole passage appears to be a satirical reaction on Dickens’ part to the practice of sending valentines, and the industry behind them. We might only look to his description of the window display in the stationers that initially entices Sam Weller:

The particular picture on which Sam Weller’s eyes were fixed… was a highly-coloured representation of a couple of human hearts skewered together with an arrow, cooking before a cheerful fire, while a male and female cannibal in modern attire, the gentleman being clad in a blue coat and white trousers, and the lady in a deep red pelisse with a parasol of the same, were approaching the meal with hungry eyes, up a serpentine gravel path leading thereunto. A decidedly indelicate young gentleman, in a pair of wings and nothing else, was depicted as superintending the cooking; a representation of the spire of the church in Langham Place, London, appeared in the distance ; and the whole formed a “valentine,” of which, as a written inscription in the window testified, there was a large assortment within…

Charles Dickens. The posthumous papers of the Pickwick Club: containing a faithful record of the perambulations, perils, travels, adventures and sporting transactions of the corresponding members. London: Chapman & Hall: MDCCCXXXVII [1837]. Chapter 33. NAL. Forster 2443 or L.917-1970 https://nal-vam.on.worldcat.org/oclc/28228280

If you don’t feel quite as cynical about the marking of the occasion as Dickens, then you might like to learn more about Victorian Valentine’s Day cards within the V&A collections, in this post by Sarah Beattie. These cards can be viewed at the Prints and Drawings Study Room, whilst the Pickwick Papers and Valentine writer form part of the National Art Library collections. Both study rooms are currently open Wednesdays only, see links for opening details…

Now time to get writing!

An interesting blog with a lot of entertaining info especially about the negative answers you could give! Glad the card companies don’t make those sort of suggestions these days. Great stuff.