Is it possible to engineer serendipity in the museum? This is a question that we have been trying to answer as part of Show+Tell+Share – a V&A Research Institute (VARI) project funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Over the past year, through desk research, workshops and the development of a digital prototype, we have been exploring and experimenting with the concept of this evocative word whilst trying to design for serendipitous moments and encounters in the museum.

The word serendipity was coined by 18th century writer Horace Walpole in 1754 after reading The Three Princes of Serendip. Walpole used the word to describe how the heroes of the Persian fairytale were ‘always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things they were not in quest of’. Today, we might use the word to explain a happy accident mixed with insight or meaning. Moments of serendipity can be found throughout our everyday lives – in the unplanned ways that we find interesting and surprising connections between information, people and things – often playing an important role in how we discover, explore and learn.

Researchers have highlighted the ways in which museums, stores and archives encourage unexpected discoveries.1 In museum stores the undisplayed, sometimes overlooked and seemingly disorderly nature of the objects stored in these spaces often allow for unexpected interactions, connections and imaginations to weave throughout. Here, on shelves, in drawers, boxes and cabinets or hung up on rails, accidental groupings of colours, patterns, materials and shapes create interesting unintentional displays. Where rare and culturally significant, ‘show-stopping’ and spectacular artefacts might sit alongside the commonplace, the everyday, the worn and the damaged.

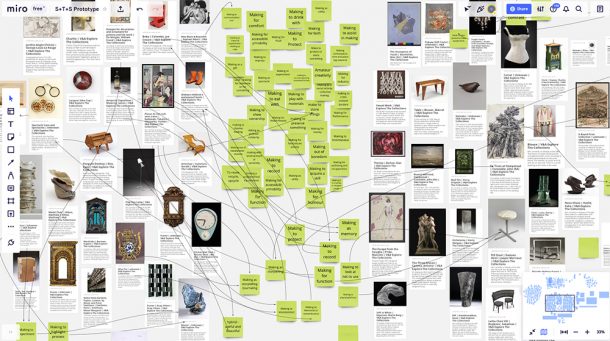

We started to think about how we could design tools that could replicate aspects of experiencing objects in storage (especially with the new V&A East Storehouse in mind); and how we might create opportunities for unexpected encounters with the V&A’s vast and varied collection. This resulted in the design and development of a digital tool that we have called the Serendipity Prototype. Borrowing from information scientist Lennart Björneborn, ‘even if we cannot “design serendipity”, we can design for serendipity’.2 The Serendipity Prototype collects and displays user-generated connections between the V&A’s objects – prompted by various questions. As the name suggests, it is still very much a work in progress but our ambition is that it will allow users to create and drive meaningful object encounters for other users – where an interaction with one object will lead to multiple pathways through, and meetings with, other connected ones.

Building object connections through workshops

To help build our prototype, we asked our colleagues from the V&A, as well as external participants (including students and members of the public) for their help in making connections between the V&A’s objects. Early experiments with students from the Royal College of Art (RCA) History of Design MA and PhD programme provided us with connections based on their own work and research within the museum and collections. Connections ranged from objects’ shared materials, shapes, colours, sounds and patterns (‘nylon’, ‘ball’, ‘grid’, ‘blue circle’) – while others spoke to more thematic connections, including ‘atomic’ and ‘garden city movement’.

After this first experiment, we developed a series of online Serendipity Workshops where we could build object connections in a more facilitated way. We were looking for object connections that would potentially go beyond what can be found or generated in the museum already (e.g. through image detection technologies or cataloguing tag sets based on key words) – connections that might capture more lived, personal and emotional insights. Before the workshops – and inspired by 19th century designer William Morris who said ‘have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful’ – we asked participants to send us objects from the collection that they found most beautiful and most useful. This exercise, in itself, was an opportunity to uncover lesser-known objects in the collection built on people’s personal knowledges and interests, and based on opinions of beauty and usefulness. The workshops created a space for a constant flux of objects, as if we had walked into our own museum store.

We then used these objects to prompt discussions through questions of making – specifically asking participants ‘why do you think this was made?’ Making motivations is a lens being explored by the V&A East team as a curatorial framework and we wanted to build on this. Through these conversations, participants drew lines between their objects and the (often multiple) making motivations that they thought surrounded them: making to protect, to record, to experiment, to impress, to protest, to memorialise, to communicate, to eat, to drink, to heal; making for comfort, for function, for humour, for decoration, for faith; making as identity and making as a tool to make something else. Through the course of the workshops, object connections for the Serendipity Prototype were being built in real time as more lines connected objects to each other in interesting ways.

Serendipitous encounters with stories

One of the most exciting (and serendipitous) elements to come out of the workshop was how participants started to attach their own personal insights, experiences and reflections onto the ‘useful’ and ‘beautiful’ objects. In doing so, we were taken to new spaces, places and possibilities of understanding. In our everyday lives, we habitually attach stories, meanings, memories and knowledges to objects. During the workshops, to think about why something was made was also to think about how that process of making connected to the participants in more personal ways.

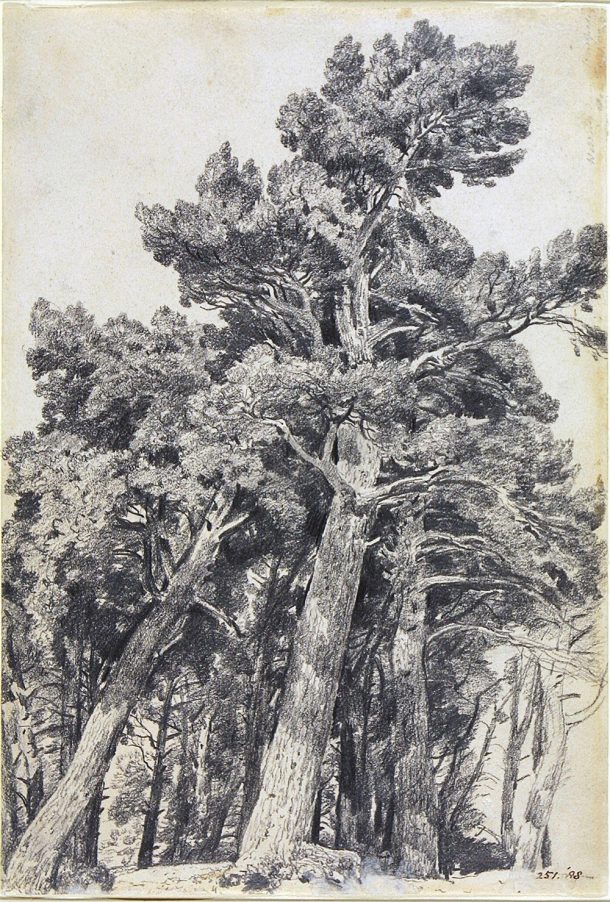

A John Constable pencil drawing titled Fir Trees at Hampstead, which depicts a cluster of trees, drawn from a low viewpoint in Hampstead, London, elicited the making motivations: ‘making for storytelling’, ‘making to record a place’, ‘making in place’ and ‘making to remember’. But from here we were taken back to childhood camping holidays, sat in the back of a car whilst driving through forests. “I have never actually been to Hampstead Heath but the pencil drawn trees capture a feeling that I can’t explain… a feeling of familiarity”, explained the workshop participant.

Meanwhile, a chandelier called the ‘Fragile Future Chandelier’ (‘made to contrast’, ‘made to raise questions’ and ‘made to make people think about the built environment and nature’) opened up material conversations about concrete. The object transported us back to the summer of 1999 and to the countryside in the newly formed Republic of Moldova – from memories of childhood and self-build concrete homes built with vernacular tools (bed springs to sieve and bathtubs to mix aggregates), to imagining the future sustainability of concrete airports transformed into spaces of rehabilitation. Read more about this memory.

Encountering objects through other people’s stories can often create more interesting interactions and make us think about objects in new ways. We all bring our own memories, stories, experiences and embodied knowledges into museums, whether that is as a visitor or someone who works/volunteers there. This is something that we have been reflecting on whilst building the prototype. How could we also include the polyvocal voices – the complex multiple social, emotional, material and sensory relationships and narratives which surround the V&A’s objects and materials – within the prototype. How do we attach these voices to the threads that connect objects so that serendipitous encounters with objects also led to serendipitous encounters with stories; how do we create environments for this to happen and what other questions could we ask?

1 See for example: Bond, S (2018) ‘Serendipity, transparency, and wonder’ in Brusius, M & Singh, K (Eds.) Museum Storage and Meaning: Tales from the Crypt, London: Routledge.

2 Björneborn, L (2017) ’Three key affordances for serendipity: Toward a framework connecting environmental and personal factors in serendipitous encounters’, Journal of Documentation, 73(3), p. 1070.