With a multitude of names from ‘Dutch Wax’ to ‘Liputa’, wax print textiles are found in African homes across the world and have become an important part of African cultures.

Selvedge Magazine

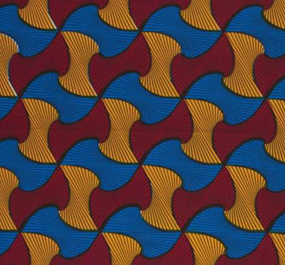

For many, the printed fabric known as Ankara, Dutch wax, African Wax Prints or batik is a cloth synonymous with Africa. The fabrics’ bold patterns and bright colourways are interwoven with the history, artistry and identities of the African diaspora and have forged part of its cultural heritage.

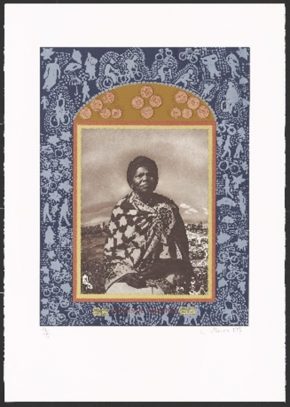

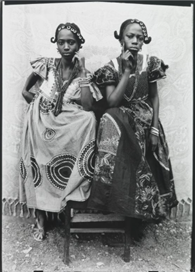

The patterned cloths form the backdrop of Seydou Keita’s photo studio, and feature on the wrappers and headscarves of women’s clothing across the photographs of Amsatou Diallo, Malick Sidibé and Abderramane Sakaly. In Sue Williamson’s A few Good South Africans series, the sitters and their frames burst with batik and kanga cloth-inspired patterns.

Scramble for Africa (2003), an installation by Yinka Shonibare MBE RA, features 13 headless figures dressed in Dutch wax frockcoats. The figures represent the European powers carving-up the African continent in a formalised division in 1884 – 5. The cloth with its links to European manufacturers, like Vlisco and Logan, Muckett & Co. also represents the ongoing economic influences of Europe’s colonialism on Africa.

Dutch wax cloth with its myriad of colours and designs has found widespread aesthetic appeal across the world. It has been the fabric of choice for fashion houses like Stella Jean, Valentino, Marc Jacobs, and Givenchy, and for stellar performers such as Beyonce Knowles-Cater, Rhianna, Tracee Ellis Ross, and Keke Palmer, who look to celebrate as well as align themselves with the styles of the African diaspora. But these fabrics function beyond any aesthetic appeal. In many African countries the subject matter, colours and names of the printed fabrics are imbued with cultural signifiers that have made these prints ‘a symbol of strength and identity in the face of oppression.’

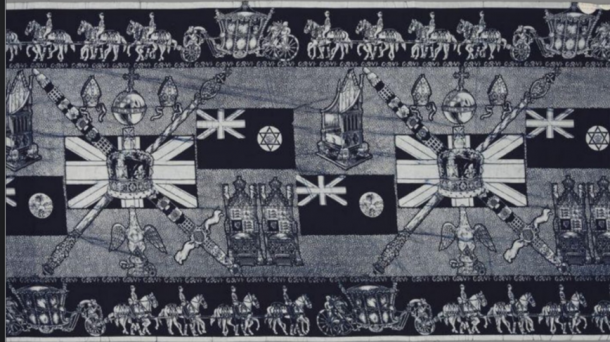

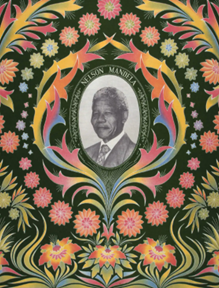

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the commemorative fabric prints of prominent figures, who literally wear their allegiances on their sleeves.

Textile of printed cotton. Commemorating the Coronation of King George VI. Logan, Muckelt & Co., Great Britain, 1937, Museum No. CIRC.372-1966, ©V&A Museum

Nelson Mandela Commemorative print, designer unknown, ca. 1990, photographer unknown

Nelson Mandela Commemorative print (4990R) designed by Jan Mollemans, 1990, Vlisco, Holland, © Vlisco Group

In the case of the commemorative Nelson Mandela prints, the cloth not only celebrates a pivotal figure and a moment in South Africa’s history, but it is also a symbol of political resistance. Prior to Nelson Mandela’s release from prison on 11 February 1991, the National Party’s government made it illegal to publicly display Mandela’s likeness or the colours of the African National Congress party (ANC). In the wake of Mandela’s release and the subsequent fall of South Africa’s oppressive apartheid system, these printed cloths with Mandela’s portrait and the ANC’s colours of black, green and gold were mass-produced, widely distributed and proudly worn publicly.

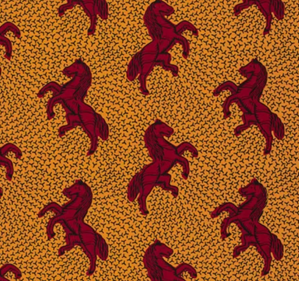

In non-commemorative prints the subject matter, names and meanings are more abstract and open to interpretation. In Nigeria the wax print VL53500.028, known as the Jumping Horse pattern, is the chosen design of the Igbo women for their Aso-Ebi (family cloth) to express familial or communal links between women. In the Ivory Coast it goes by the name I Run Faster than My Rival, and in contrast expresses ‘the rivalry between co-wives’

Across different regions and countries, the same patterned fabric goes by different names and has been imbibed with varying social signifiers. On the Vlisco website there is a section dedicated to the stories behind the fabric. Examples featured on the site include You leave, I leave, a fabric featuring two birds and a bird cage. According to the Vlisco catalog, its meaning is ‘If you are unfaithful to me, I’m not going to restrain myself either’.

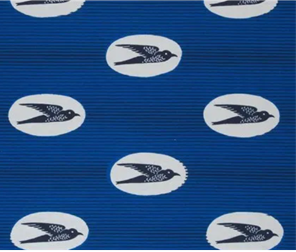

Another example is print VL0H524.061, called Speed Bird but also known as Air Afrique in Togo and Rich today, Poor tomorrow in Ghana and Eneke in the Ebo region, which boasts as many meanings as it does names, all drawing on the themes of change, prosperity and freedom.

Print VL03686.024, known as Santana, as well as Darling don’t turn your Back on Me is a three-colours pattern that was named after Madame Santa Anna Nelly, an influential Togolese cloth trader who had secured exclusive rights over this rare pattern. Nelly was one of the several powerful businesswomen in Togo given the name ‘Nana Benz’.

The ‘Nana Benz’ provided a bridge between local consumers and European manufacturers, such as the Dutch firm, Vlisco, the British firm, GB Ollivant and the French Société Generale of the Gulf of Guinea (SGGG). The moniker ‘Nana Benz’ refers to their social standing as the matriarch ‘Nana’, mother/grandmother and ‘Benz’ reflects their financial success, epitomised in the ownership of a fleet of Mercedes Benz cars. The first generation of ‘Nana Benz’ amassed huge fortunes through the sale of Dutch wax fabric, feeding local demand and creating a huge local economy. This economy was built on access to fabrics that started with 10-15 key ‘Nana Benz’ at the top controlling the wholesale imports through to semi-wholesalers, then legions of retailers and finally street hawkers. In 2004 on average the fabric trade turnover ranged ‘between 10 million and 2 billion CFA francs (15,245 – 3,049,000 euros)’ and that one Nana Benz stated that her ‘annual turnover varied between 25 and 40 million francs CFA [35–60 thousand euros]’6 this even more impressive when we considering that in Togo ‘90 percent of its population barely managing to live on a dollar a day.

Central to that success was and continues to be the role of local retailers and saleswomen who personalised these fabrics to market them to a broad variety of customers. The fabrics, many of which were only given numbers by the manufacturers, were endowed with names and backstories by the saleswomen:

They gave the prints local and cultural meaning, truly embedding the brand into the local culture. But the meaning given to some prints also provided a way for the wearer to communicate something about herself.

Inge Oosterhoff

These prints were imbued with cultural signifiers that the wearer adopts to telegraph to the world their feelings, aspirations and identity. An example of this is print VL00017.019, the Alphabet design, which is meant to convey the wearer’s pursuit of education either for herself or for her children.

A recent example is the 2008, Super wax print A110 by Vlisco 6 also known as, ‘Michelle Obama’s Handbag’. Not only is this a superior, thinner cloth with additional colour layers, printed by a foreign brand making it expensive, but the retailers inferred additional prestige by linking it to Michelle Obama. As writer and anthropologist in African Wax Print Textiles, Anna Grosfilley states:

The basic appeal translates as: “You cannot afford to be Michelle Obama or buy the same bag as she carries, but because you can buy the pattern on wax print it’s like you’re part of it.

Anna Grosfilley

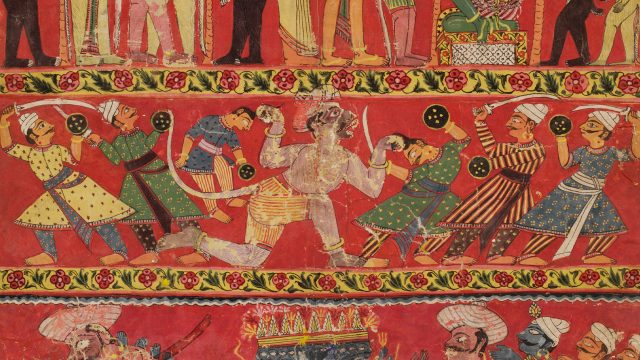

The patterns and designs of these Dutch wax prints reflect the complex interconnections between the continent and colonialism and between modern technology and historic craftsmanship. The history of these fabrics in Africa is a relatively new one and the provenance of the popular prints is immersed in colonialism and exploitation. The mechanism of creating African Dutch Wax prints has its origins in Indonesian batik, the process of applying wax resist-dyed patterns to cloth. Indonesian batik was made by artisans who use a small copper vessel (a tjanting) to apply melted wax in intricate designs onto cotton, which is then dyed, more hot wax designs applied and then dyed again over the period of several weeks. In 1811, the process was diligently documented by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, during Britain’s rule over Java. Raffles sent back to Britain examples of the batik prints along with his instructions. His intention was to mechanise the process to produce cheaper mass-produced prints that could be sold back to the Indonesians, however it was the Dutch who successfully adopted Ruffles methods to ‘mechanise the process so they could undercut expensive hand-made batiks‘. Exports of the cheaper machine-made prints to the Dutch West Indies began in 1850. The cheaper prints were no substitute for the Indonesian art form, and the imports found little purchase in those markets; instead they found a customer base in West Africa. According to Anne Grosfilley, the fabrics appeal to these consumers for the following reasons:

These industrial prints inspired by Javanese batiks were ideal: light material, but with an indigo base – they were exotic in a way, but also had some similarities with the West African traditional local tie-dye.

Anne Grosfilley

European brands such as Vlisco and ABC provided beautifully designed prints which offered a quicker and cheaper alternative to traditionally designed and made African cloth, which was resource heavy. The firms’ success has sparked competition and imitations from China, India and Pakistan have now flooded the market. The imitation prints are so good that even experts struggle to tell them apart from the original. The rise in fakes has prompted companies like Vlisco to develop new verification processes to ensure authenticity. At a fraction of the price, these hard-to-detect fakes are replicating the same business model of cheap foreign import that imitated and undercut the traditional providers, that Raffles formulated 200 years earlier. There has been growing criticism of imported Dutch wax prints either made in Europe or Asia due to the disconnect between the consumer and the producer:

People were connecting with the fabric as a representation of their identity, of their culture, of a place or heritage, however, it had no economic benefit to that place.

Clare Spencer

The false idea that these designs are African or created by African firms is due in part to the longevity of these products, designs like Brown Fleming’s design known as ‘skin’ or ‘house marbles’ have been worn by generations of consumers for over 125 years. The second reason is that the manufacturers have adopted African names, firms like the Ghana Textiles Printing Company (GTP), which is owned by the Dutch firm Vlisco or Akosombo Textiles Limited (ATL), which was named after the river in Ghana but was until recently a Chinese firm. Ultimately the designs have become entwined with Africa’s cultural heritage because its consumers have shaped its designs and supported this market:

The ecosystem and visual language of its trade is a cultural phenomenon in which women entrepreneurs flourish, and individuals can forge and display their identities through design.

Sarah Archer

The British-Nigerian film director, Aiwan Obinyan, unwraps the problematic issues of how ‘one fabric came to symbolise a whole continent‘ despite foreign production and ownership in her evocative documentary Wax Print (2018). Obinyan followed the fabric’s journey from ‘village to cotton field, from mill to market’ and during her investigation has come to reject Dutch wax opting for locally produced cloth. Her documentary serves to shine a light on Africa’s ‘indigenous textiles including Raffia, Bogolan and Mudcloth and a wide-range of textile production methods from tie-dye to weaving’. Cloth like Bogolanfini or ‘mud cloth’ is made by the Bamana people of West Africa and uses plant-based dyes, fermented mud and multiple dying stages to produce a black and white patterned design.

Raffia, also known as Kuba cloth, is woven and embroidered using dyed palm fibres in shades of yellow and dark brown. An iron needle is used to thread the lightly twisted fibres through the ground, and both ends appear on the surface. Like velvet, the threads are cut so that only a few millimetres remain visible and produce a thicker fabric. These beautiful cloths are in many ways the antithesis of Dutch wax prints with every part of their production, from design to material, rooted in Africa. Their continued production in the face of cheap, mass- produced imported wares, is however dependent on an informed and financially able consumer base willing to forgo fast fashion.

The V&A plans to stage a major exhibition celebrating the irresistible creativity, ingenuity and unstoppable global impact of contemporary African fashions. Opening June 2022, the exhibition will celebrate the vitality and innovation of this vibrant scene, as dynamic and varied as the African continent itself. To find out more and how you can get involved please visit the V&A blog: V&A Africa Fashion call out

Further viewing

WAX PRINT FILM: 1 Fabric, 4 Continents, 250 Years of History by Aiwan — Kickstarter

Beautiful article, I envision a pattern representing the struggle of the AADOS people in America. Please email me with a pattern designer to help tell the story. From Slavery to New Africa

Really enjoyed this article and hope there will be more to come as the research continues.

“Africa” so often confused with the idea it is one country… and every country within having many tribes and origins and stories to tell. On the cave walls to the mudhut walls, to the fabric of everyday use and simply decoration.

Look forward to the sequel.