My time here at the museum has been closely linked with the arrival of The Royal Photographic Society (RPS) Collection to the V&A by the Science Museum Group in 2017. I was involved in unpacking the RPS material and since January 2018 I have been cataloguing the collection full-time. As part of this work, I have seen many treasures from the rich RPS holdings, including pictures by esteemed masters of photography such as Julia Margaret Cameron and William Henry Fox Talbot. However, I have also seen much lesser known work and discovered exciting examples of quirky and experimental photography, including the print below that I happened upon earlier this year.

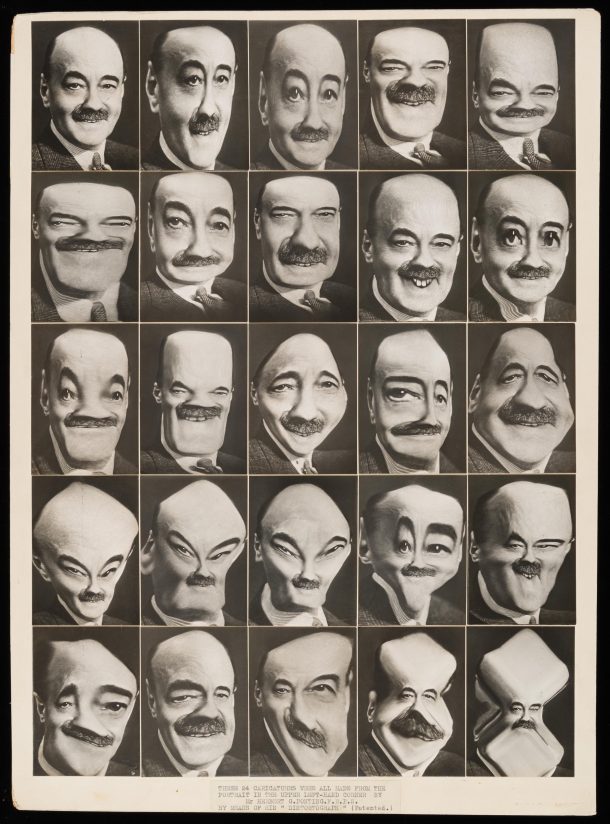

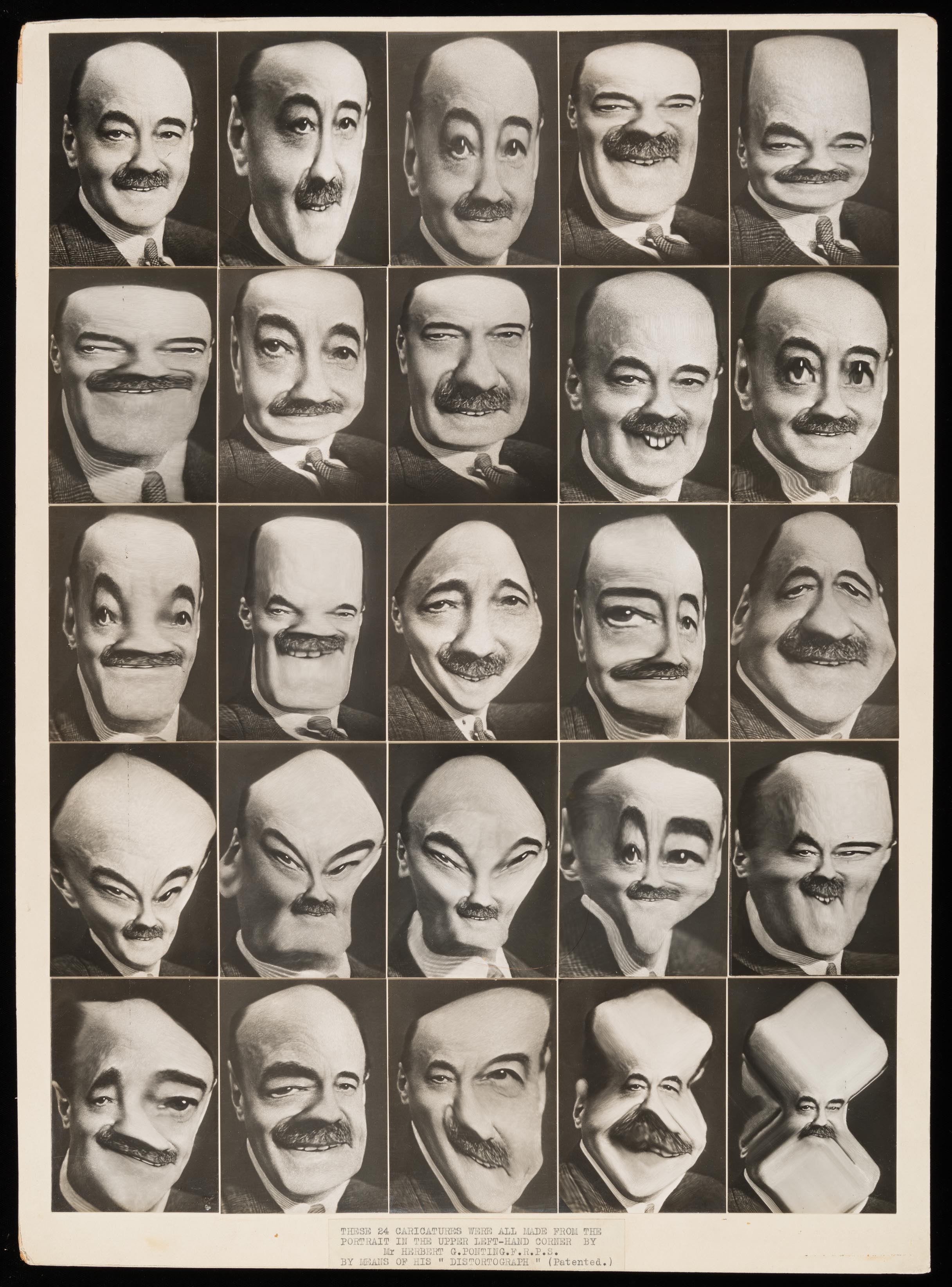

This photograph is a grid of 24 distorted portraits, all made from an original image that can be seen in the top left corner. To my surprise, I saw this print was made by Herbert Ponting: surely not the same Herbert Ponting who photographed Robert Falcon Scott’s Antarctic expedition of 1910-13? I decided to do a bit more digging into the background of this print, which revealed an unexpected and strange story about Herbert Ponting and his business partner George Ford. It spoke of business ventures tried and failed, and photographic manipulation in the pre-digital age…

Herbert George Ponting, from fruit rancher to photographer…

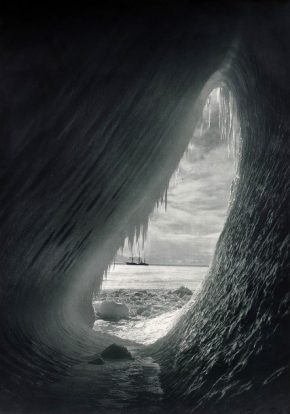

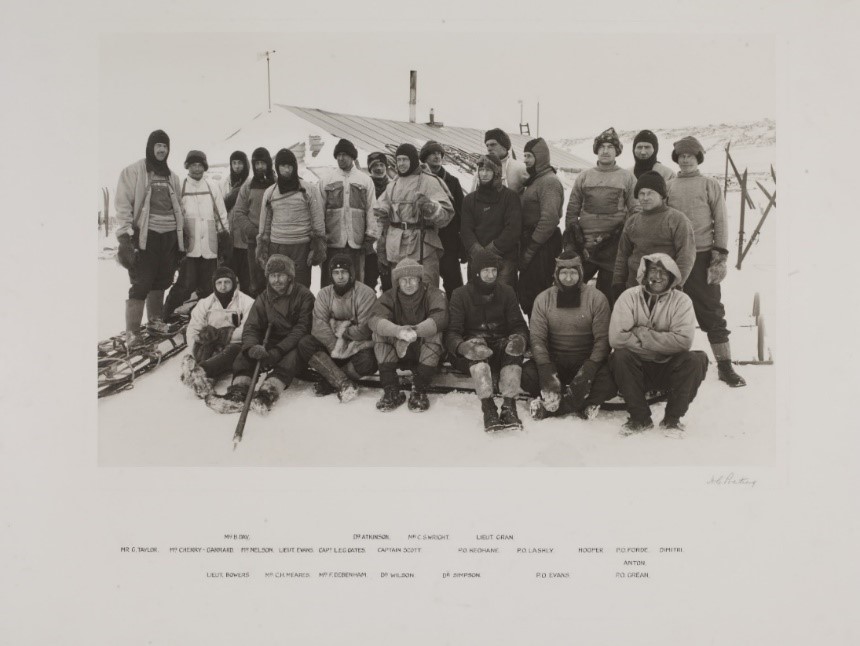

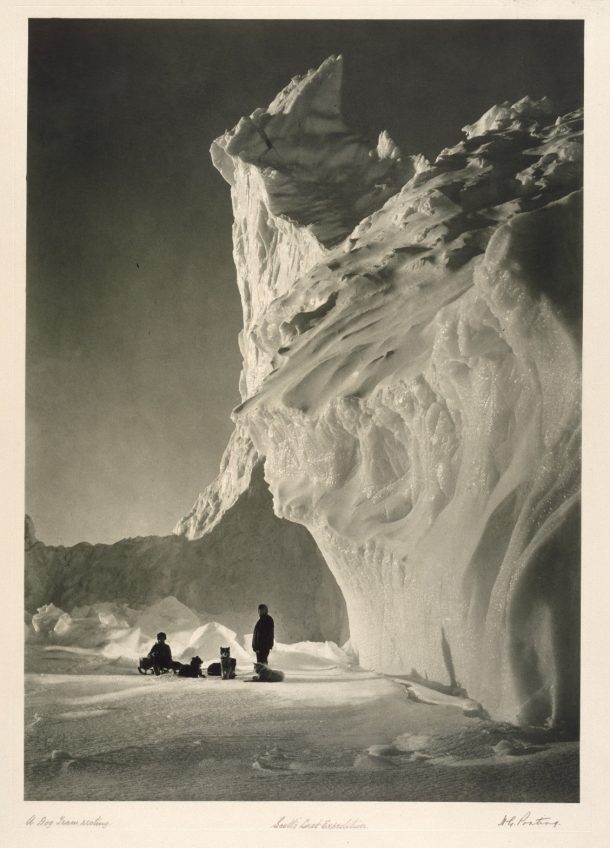

Herbert George Ponting, FRPS, (21 March 1870 – 7 February 1935) is most well-known for his photographs and cinematographs of Scott’s Terra Nova expedition of 1910-13, now hailed as some of the most iconic images of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

However, Ponting also had aspirational business intentions and attempted on numerous occasions to popularise his experimental inventions.

Born in England, Ponting’s first commercial venture involved moving to the American west to operate a fruit ranch. However, perhaps forewarning what his future luck would bring, the business ran into difficulty. He returned to England in 1898 with his wife, Mary Biddle Elliott, and their daughter Mildred.

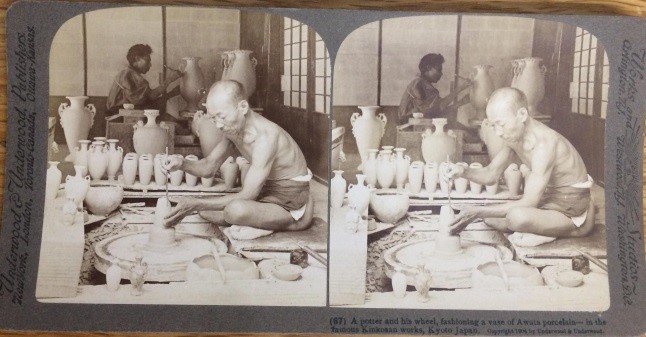

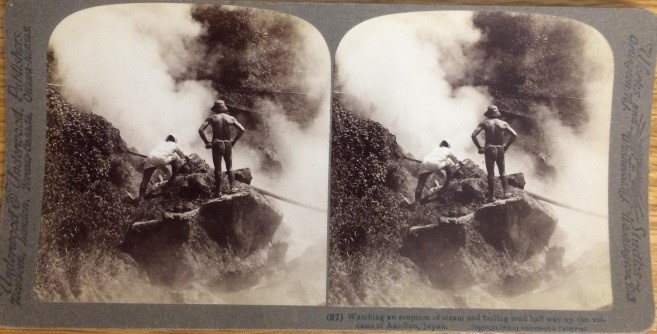

Following his return, Ponting embarked on his second career as a photographer. He quickly became well recognised and reported on the Russo-Japanese war of 1904–05, after which he continued to journey around Asia.

Ponting travelled extensively in Burma, Korea, Java, China and India making stereographs and working as a freelance photographer for English-speaking periodicals such as Harper’s Bazaar, and Illustrated London News.

The Terra Nova Expedition of 1910-1913

Ponting was chosen to be the first professional photographer on an Antarctic expedition, as part of the ill-fated Terra Nova expedition of 1910-13.

He took over 1700 photographs of the expedition, many on a metal, folding quarter plate camera that was strong and light enough to be taken on sledging expeditions.

Ponting returned from this trip in February 1912 and was waiting for Scott so that his images could be used to illustrate Scott’s planned lecture tour. However, owing to the tragic end of the expedition, with the bodies of Scott and his companions found on the Ross Ice shelf in November 1912, Ponting’s images took on sorrowful connotations. Images of the expedition were used extensively in the press at the time, but they inevitably did not have the celebratory tone Ponting originally hoped for.

Business ventures after the expedition

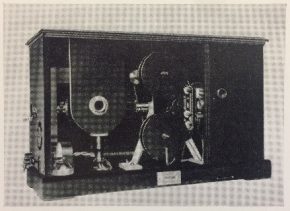

Ponting was not, by all accounts, a technically minded man, and as such had employed the services of George Ford, at the time an employee of Chromatic Film Printers. Their first venture together was the ‘Kinatome’ projector, a portable device which, for the first time, allowed film to be rewound within the machine itself. However, the use of an unfamiliar film gauge (between 11 and 12mm rather than the standard 35mm at the time) meant that, despite its promising beginnings, the projector ultimately failed to be adopted by a burgeoning market for moving picture projectors.

This came at a huge personal cost to Ponting of over £20,000, and reportedly over $250,000 from Ponting’s American associates. Ponting wrote to his friend Frank Debenham stating at the time that he had put his last shilling into the project. In spite of these struggles, Ponting remained optimistic, reassuring George Ford that the projector was being extremely well received in America and that it would undoubtedly bring them thousands of pounds. Unfortunately, it was not the commercial success that Ponting had hoped for.

The Variable Controllable Distortograph

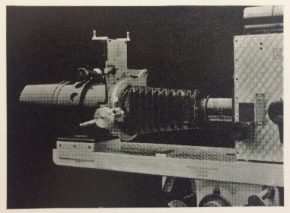

Despite this setback, Ponting convinced Ford that their next venture would allow photographers and film makers ‘to realise their ideas in a manner that has never hitherto been possible’. This venture was the ‘Variable Controllable Distortograph’. The image to the right depicts the lens Ponting used to make the grid of portraits I found in March.

Ponting envisioned a lens capable of both creating in-camera distortions and distorting pre-existing film when used with a projector. It appears that it was George Ford who created the technical concept for the lens and the detailed design work. However, all the press at the time described the invention as Ponting’s, who indeed patented the design in his own name, though he referred to himself as ‘co-creator’ with George Ford.

Ponting was convinced that the Distortograph was better than anything that had preceded it and held extremely high hopes for the invention’s success, enthusing about it in letters to Frank Debenham as ‘the funniest thing ever done in photography!’ In a descriptive leaflet for the lens, he waxed lyrical about a plethora of film effects to be achieved, including ‘visions, delirium and nightmares!’

Unfortunately, once again the aspired success did not materialise and there is little evidence of the Distortograph being used in the motion picture industry, with critics claiming that the lens was neither funny nor grotesque enough to make any real impact. This second failure encouraged Ponting’s disillusionment with the film industry and George Ford was apparently actively advised never to work with Ponting on any future inventions.

Though the quirky photograph of distorted portraits from the RPS Collection did not reveal the most successful story, Herbert Ponting and George Ford did appear to be ahead of the curve with their enthusiasm towards the possibilities offered by the Distortograph. Today, however, every smartphone has varied options for distortion, both in still photographs and moving images.

Photographs by Herbert Ponting are available to view in the Prints and Drawings study room, alongside the rest of the V&A Photographs Collection. Please visit Search the Collections to browse our online catalogue.

Hello! I think the subject of the Distortograph may be Ponting himself. Ponting and Ford’s patent is number 278,402 of 31 May 1926. Also, the camera illustrated above might be better described as a folding rollfilm camera.

Michael, thank you so much for the information and sorry to only just acknowledge your contribution, I will update our records accordingly!