Joana Choumali is an Ivorian photographer who lives and works in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. Her body of work centres on conceptual portraits, mixed media and documentary photography. She was awarded the Prix Pictet – the prestigious international prize for photography and sustainability exhibited at the V&A in 2019 – for her series Ça va aller. The V&A was pleased to acquire four photographs from this series for the permanent collection. Here I talk about her practice, memory and hope.

We are so delighted to have your work come into our collection. It is such a moving series of photographs and is quite literally stitched with emotion. How did this project come about?

Thank you. I am grateful to have my work coming into your collection. I started the project less than a month after the March 2016 Grand-Bassam terrorist attack, when three gunman opened fire in the streets and at beach resorts. The images in the series are all taken on my smartphone. I went to Grand-Bassam to attend a conference organised by the Ivorian society of psychiatrists. The conference’s theme was ‘how to cope with the trauma of a terrorist attack’; to explain to the population of Grand-Bassam how they could understand and work on their trauma and to encourage them to come to the free consultations at the General Hospital of Grand-Bassam. This was because, except for the first week after the attacks, people would hardly talk about their experience and their trauma.

After the conference, I walked around the little town and shot pictures of the neighbourhood. Three weeks after the attacks, the atmosphere of the town had changed. The energy was different, as if life was painfully running in a melancholic slow motion. Most of the pictures show people by themselves, walking in the streets or just standing, sitting alone, lost in their thoughts. And empty places … It was only after this, when back in Abidjan, that I realised that my state of health would not allow me to continue to work on the documentary project I was planning to start. But the urge to express myself was still there.

So, from home, I started to embroider on the prints of the street photos shot with my smartphone as a way of coping with my own emotions as if I was connected to the people in the photographs. I had this urge to express myself and to continue to work, to spend time with the pictures and eventually, to connect with the landscape and the reminiscence of what I felt when I was in Grand-Bassam.

Embroidery is clearly an important part of your work and you have used it in more than one photographic series (Translation, 2017). When and how did you start to embroider?

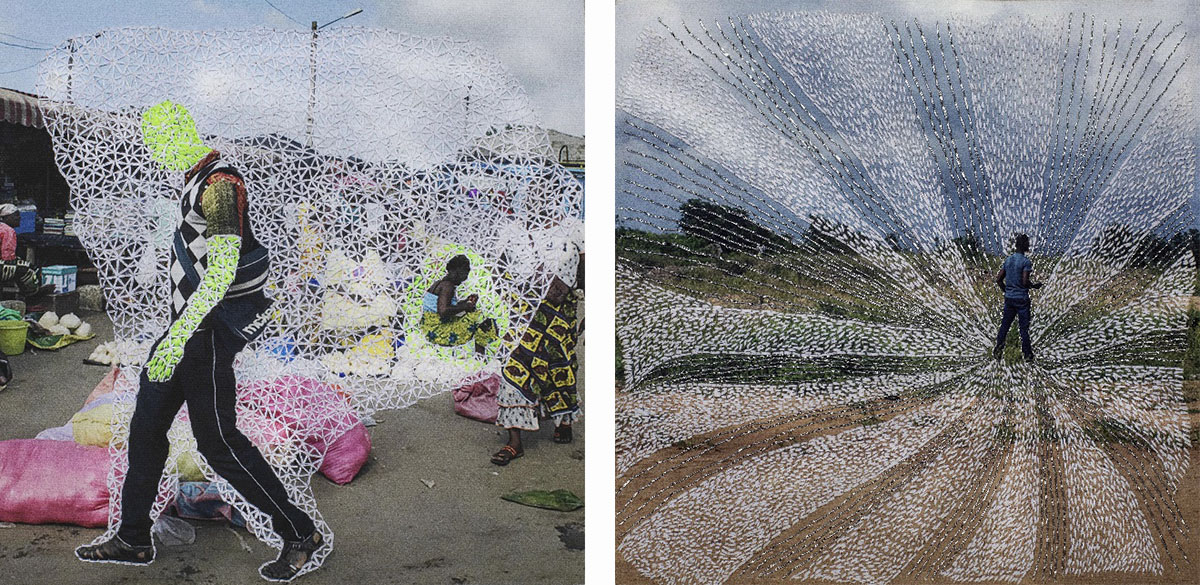

My use of embroidery was in response to an instinctive need to touch and physically intervene on my photographs. With my series Adorn, I added beading on some pieces of machine embroidery that I photographed again to create a digital collage. At the same time, I worked on Translation, a series of diptychs about migration that were exhibited at the Ivorian Pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale. The fact that I was able to allow myself to embroider on my images in an instinctive way really marked a turning point in my way of understanding and processing life through my art. My inner universe merges with the exterior; the photo I shot. This meditative approach allows me to discover another way of experiencing certain events in my life.

I am self-taught in embroidery. I started in a very instinctive way, always using the same stitch, as if it was to repair a wound. I am particularly drawn to the idea of spending a lot of time on a picture that was shot in a snap. It sometimes took me several weeks to work on one picture, to ‘download’ energies, thoughts, feelings, hopes, fears, joys etc. It can be compared to automatic scripture. I remember my maternal grandmother used to stitch all day, doing patchworks with little leftovers of wax fabrics. I was fascinated by her patience. These kinds of patchworks are called NZASSA, N’zassa meaning in Agni (a language of Côte d’Ivoire) a type of fabric resulting from the arrangement of several pieces of loincloths of various patterns and colors. N’zassa also represents the unity of the numerous cultures that you can find in my country, coming together as one. Different yet complementary.

My grandmother used to stitch for hours and I wondered why she would put so much effort in stitching with a needle and a thread when she could use the sewing machine that she also used for the dresses that she made for herself. I would often ask her why she would not use her machine and she would just softly smile at me, with no answer. Today, I fully understand the effect of hand stitching. It is so hard to describe, yet so obvious. At first, I did not really plan to show this project, so I naturally started as if I was sketching on the pictures, in a free and instinctive way.

I love the meditative state in which one can be while embroidering. It is a very specific feeling. Soothing. It has had a very positive impact on my life. Each medium is important as it merges into one piece. In the meantime, I like to push the boundaries of photography. To explore other ways to use photography in a more personal, intimate way. At a slow pace.

A sense of memory and location are central to your work. Can you describe the journey and process to undertake these photographs?

For Ça va aller, the very notion of observing this bruised and bereaved city made me realise how full of life and joy it was before. I recognised and captured a point of hope in these difficult times by reminding myself of what this space was before, by acknowledging the contrast of what it had become following the terrorist attacks, and by visualizing and projecting into the aftermath, while accepting the fact that it may never be the same again. This is an act of hope and resilience that we can all do. For me, it translated into a creative process. I focused on an observation of the streets I photographed, then I filled these empty spaces with these colored threads.

My art comes from this perception of the environment and the tacit connection I feel between the people I photograph and myself, as well as the relation to space, to the landscape, the ambient energy of a place. The non-verbal dialogue that can take place with the other and with an environment. I use my imagination. I focus on the meeting point between my emotions and how other people’s emotions contribute to this captured moment.

When I shoot a picture, I feel like I receive something, and I also leave a part of myself. Art allows me to start this dialogue of hope with a place or a person. The act of photographing and then the act of embroidering for me is a logical extension, a response to any situation. Just being a witness to this situation can make me an actor in it. It is in my nature to observe and focus on the positive and what I can learn from a situation. No matter what happens.

It is a very slow process, a big contrast with the way I used to work before. At the same time, the act of spending more time on the pieces can also be painful, because it can force me to explore moments and thoughts that I would have avoided exploring when shooting a digital photo. This idea of working at a slow pace can be challenging, as it reveals unexpected aspects in the process. It is a constant discovery, part of my inner journey. It takes patience and consistency. The act of embroidering is time-consuming, the process is long and intricate and can be tiring. For example, I do not work when I feel sick or tired because it would lead me to errors and damage the piece. I organise my process to work on the most fragile parts of the pieces in the morning, when my eyes are not tired. It has even changed my relationship with time in a certain way. My perception of time. To spend a month or more on a single picture before finalizing it was never something that I had planned to do before. I would say it is a life changing experience.

The photographs are a relatively small format (24 x 24 cm) but hold an incredible weight and power to them. How much do you think about the scale of your pictures when you’re making them?

When I first started Ça va aller, I chose a small scale, because I wanted to be able to work on it at any occasion, sometimes from my room. I would always carry one canvas with me in a little bag and embroider in the traffic etc. I was stitching every day, all day. In that sense, the small scale was very helpful, as I could work everywhere. But at the same time, intensity and focus was necessary, as the stiches were very small. Some pieces have stitches smaller than a millimetre, small dots repeated, it seemed infinite. The intimate aspect was important as well. As if I was whispering through the work. The power of a piece doesn’t depend on the scale. Actually, both big and small pieces can convey strength.

Your photographs, along with the other works in the 2019 Prix Pictet exhibition, have continued to tour the world throughout the pandemic. The theme of this edition of the prize and the exhibition was ‘Hope’ which seems even more relevant now. Has this series changed in meaning for you since you first produced it?

Winning Prix Pictet Hope is a moment that I will never forget. I am amazed to realise that the effect and mood of my work can be communicated to the viewer. To get feedback from someone I don’t know who connects with the work is the best part. My work helps me understand life better, understand myself. It allows me to heal and grow as a human being and connect with other human beings without having to talk. To me, that kind of connection is the most rewarding aspect of being an artist. I am so grateful for receiving such a prestigious prize. I was struck by the symbolic dimension of winning that cycle of Prix Pictet with the theme of Hope. I think that the meaning of the theme Hope is even more relevant this year than ever.

You often work with your own smartphone to create your pictures, what compels you to take it out and take a picture?

The main reason I used my smartphone is that I always shoot a lot of street photos of my city, on a daily basis. For Ça va aller, I chose my smartphone instead of my larger camera, because I was including myself in that process. I wanted to photograph people in a natural behaviour, and not to bother them with a big camera. It is part of this intimate and respectful process.

The title of this series, Ça va aller, is French for ‘it’s going to be fine’. It’s a sentence I think many of us are guilty of saying to ourselves and to others at a time where things are probably not fine. It’s almost a coping mechanism. Why this title for this body of work?

When someone starts a conversation about a difficult, or sad topic, people would end the conversation with this expression: ‘ça va aller’. It translates to ‘It’s going to be fine’, a common phrase used by people in Côte d’Ivoire to casually reassure each other, even after a deeply traumatic event. This situation happened to me when I tried to comment on the terrorist attacks with relatives, friends etc. And that is why I chose to use this expression as the title of my work. Both to convince myself that it would be fine, but also as a reminder that difficult conversations cannot always be postponed. Sometimes, it is good to face them and work on them.

Your book Hââbré, The Last Generation is also in the V&A’s collection in the National Art Library. It’s a compelling and moving book. How did this project come about, and do you feel a connection between these two bodies of work?

‘Hââbré’ means ‘writing’, ‘sign’ and ‘scarification’; this one word signifies all three notions in Kô, a language from Burkina Faso. It is a series of portraits about African people bearing the imprint of the past on their faces. Scarification went from being the norm and having a high social value to being somewhat ‘excluded’. This was how the desire to photograph these men and women was born, this last generation of scarified Africans, not just from Ivory Coast, because most of the people I photographed emigrated to Abidjan from Burkina Faso, but they’ve been living long enough in Abidjan to consider themselves Abidjan citizens. Yet, this scarification continues to remind them that they are originally from another country, and another era.

My aim was to gather the testimonies of these people who left their villages and came to settle in Abidjan to work. Several people told me that they had been the target of bullying and mockery because of their scarification. These people have had to integrate into Ivoirian society, and more specifically into Abidjan, the best they could.

When I was a child, it was common to see people with scarification on their faces. Then, I realised that it was a disappearing practice. I was intrigued by the reactions that people could have towards scarification. Some would say it is barbarism, others that it was art. But most importantly, I was curious to hear the opinion of those who were living with these scarifications in the city, in the 21st century. I took photographs of the sitters’ face-on and from behind. From behind, people could be of any origin and I chose to show everybody’s anonymous character. Face-on, it’s impossible to hide and, in this case, these people literally had to face their identity. They have no choice but to display this facial ID that their scarification represents. One of the people I photographed said to me, ‘No need for an ID card, we already have ours on our face. That was why they used to do this: for mutual recognition. But now, that’s over, we don’t recognise each other any more.’

The main connection between Hââbré and my other projects is the fact that I am exploring a social fact and trying to understand how it affects us in a more personal, psychological and non-verbal way. What makes us human, how are we affected by history, which personal stories lie behind history?

Right: New Normal, 2020. 80 x 80 cm © Joana Choumali

Can you give us an insight on any projects you have been working on recently? Have you been able to work throughout the pandemic?

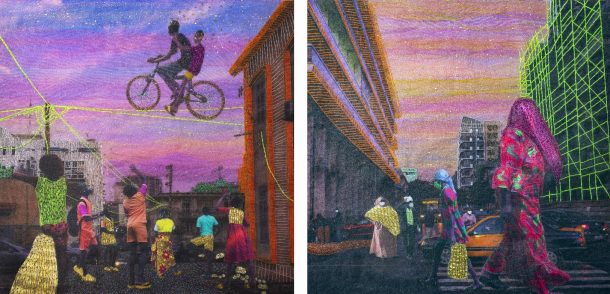

The creative process of my current and ongoing project Alba’hian is very personal. I use photography, golden paint, collage, embroidery and several layers of fabric to recreate feelings, memory, thoughts and visions that I have while I am walking and witnessing the sunrise. I let my personal memories and emotions lead me. Alba’hian, which means the ‘first light of the morning’ or dawn in Agni, celebrates the powerful energy that comes with the beginning of a new day. The new light that makes everything visible and illuminates the world as if we are born again in that moment and we embrace our inner self. I start the day by getting in contact with the land around me, observing the landscapes, the shapes of buildings or the objects slowly revealing themselves, the streets and its people awakening. The morning light at the beginning of each new day slowly makes every detail of the material world visible. This practice of observation has made me become aware of the shift in my thoughts and my perception of realities. I have been working on several pieces on this series linked to the pandemic:

Because We Played Outside As Kids captures the innocence of childhood. I shot the picture in Dakar. The colour of the sky was so vivid yet with tender vibes. I started the piece this year at the beginning of the Covid-19 lockdown. This piece is a reminiscence of my childhood in Abidjan, where all the children of a neighbourhood knew each other and met to play in the streets, ride a bicycle, dream together. In all innocence, we could experience a childhood full of certainties, where every tomorrow seemed guaranteed. It is this freedom to hope, to dream and to believe that anything is possible that is expressed in this piece. Unfortunately, since last year, the pandemic and the events that followed have confiscated a big part of that freedom and innocence from our children.

New Normal started with the silhouettes of people that I photographed in the streets. Many of them were masked, so I naturally included these silhouettes to my narrative. New Normal depicts a Monday morning in Dakar, in 2020. So, the pandemic has affected my artistic process and still does. The piece is part of Confinement, the new Prix Pictet book (2021). I continue to explore this topic throughout my work.