As one of the last Erasmus+ students in the UK, I was able to come to London from Porto and join the V&A’s Decorative Arts and Sculpture Department. I was lucky to find myself carrying baskets full of museum treasures and adding information to the online database alongside the curators, while continuing my thesis research into the relationship between Renaissance inventories and objects.

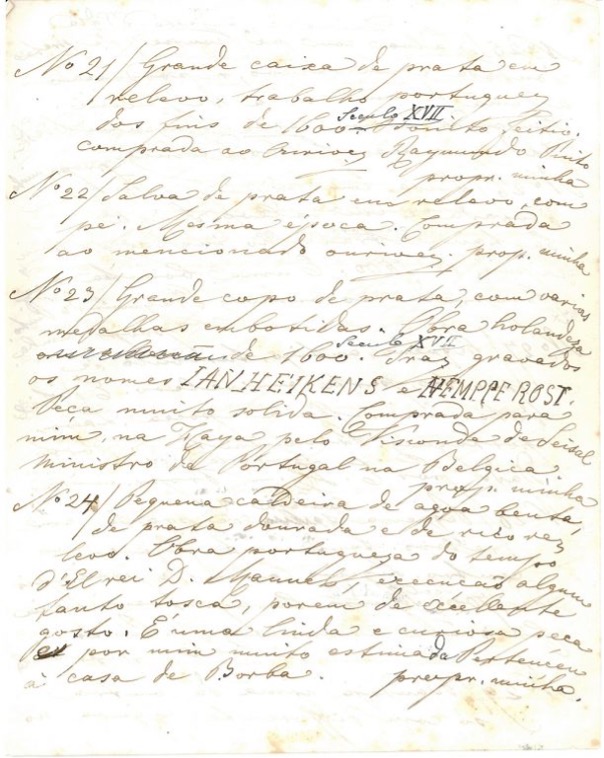

One afternoon, I joined curators Alice Minter and Sophie Morris to examine some of the early pieces in the Gilbert Collection, on loan to the V&A, and discuss the forms, materials, iconography, inscriptions and possible provenance of the objects. Unknowingly, I was about to embark on a journey of discovery: my attention was caught by this object, a silver-gilt holy water bucket made around 1560 in Burgos, Spain, with the mark of assay master Juan Abaunza, and a crowned ‘F’ on the base.

The striking silver object is shaped like a vase and is decorated with renaissance motifs that echo ancient Roman ornament. Fauns (mythical creatures that are half man, half goat), stand between medallions that frame the heads of helmeted warriors in profile. Holy water buckets contained water that had been blessed by a priest, and were used in Christian religious ceremonies as a symbol of purification and cleansing. This bucket would originally have been paired with a sprinkler, now lost. The bucket is cast and weighs just over half a kilo. Whilst we do not know for whom it was originally made, they were certainly wealthy.

We knew from the assay master’s mark (stamped twice on the edge of the foot rim) that this silver bucket was made in Spain, but after closely inspecting the crowned ‘F’ on the object’s base, the Gilbert curatorial team suspected that it had once been owned by someone royal. Dom Fernando II, King of Portugal (1816 – 85) was a collector, patron and artist who had acquired pieces of silver in Portugal and other countries. A selection of his possessions had been sold at Sotheby’s in 2012: these items were engraved with the same distinctive crowned ‘F’ cypher, to show they belonged to him personally.

Dom Fernando II’s collections were very significant in quality and quantity, and included silver, enamels, arms, armour, ceramics, glass, furniture, ivories and rock crystal. He particularly admired silver objects dating from the end of the 15th century to the first half of the 16th century, a period viewed with nostalgia by late 19th-century Portuguese collectors as the golden age of Portugal’s seaborne expansion to India and Brazil. Much of Fernando’s collection has since been dispersed, following the overthrow of the Portuguese monarchy in 1910, and is now in private and public collections around the world. A ewer listed in the inventory of his possessions was sold at Sotheby’s in 2012 and is now in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. On the other hand, 27 pieces (mostly salvers and ewers), that were the property of the Portuguese Crown passed into the possession of the Portuguese government. These magnificent pieces of goldsmiths’ work have just been placed on public display in a new museum devoted to Portugal’s royal treasures, at the Ajuda National Palace, Lisbon.

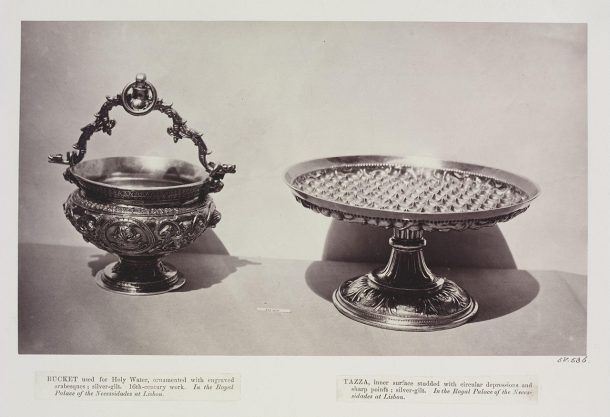

Previous experience analysing royal Portuguese inventories for my thesis led me immediately to search for relevant published sources such as crown inventories and exhibition catalogues. For example, the proposed royal provenance was confirmed by the 1882 catalogue of the Retrospective Exhibition of Portuguese and Spanish Ornamental Art held in Lisbon. There I found the following entry: “Small cauldron in gilded silver, with medallions and other worked ornamental motifs. Portuguese work. Sixteenth century […] [Lent by] His Majesty the King, Lord Dom Fernando” and an engraving of a bucket identical to the one now in the Gilbert Collection. I was also fortunate to discover that only last year Dr Hugo Xavier, curator at the Palácio Nacional da Pena, Sintra (near Lisbon), had brought to light and published an inventory of personal possessions drawn up by Fernando himself in 1866 (available to download for free.) Listed in the first book of this inventory, at entry number 24, was a description of the bucket as Fernando himself valued it: “Small holy water bucket in gilded silver and with rich relief [work]. Portuguese work from the time of King Dom Manuel, execution somewhat rough, however in excellent taste. It’s a beautiful and curious piece that is much esteemed by me. It belonged to the Borba family. My own property.”

In his study of the inventory, Hugo Xavier had illustrated this description with a 19th-century photograph of an object identical to the holy water bucket now in the Gilbert Collection, taken by Charles Thurston Thompson. Thurston Thompson, the first official photographer for the V&A (then called the South Kensington Museum), had been sent by the Museum’s director, Henry Cole, to Portugal and Spain to document representative examples of silver plate there. His brief included taking pictures of pieces in the Portuguese royal treasury, and in Dom Fernando’s own collection.

I contacted Hugo Xavier to ask him if the image in his book was indeed the photograph by Thompson, and he confirmed that it was a detail of the same picture. He was very excited to discover the bucket’s whereabouts, as he didn’t know the piece had survived. He also remarked that the object appears on a sideboard in a photograph of the interior of the King’s apartments in the Palácio das Necessidades, in Lisbon (reproduced in his book on the 1866 inventory). Xavier also identified the significance of the engraved letter and number ‘N 31’ on the underside of the bucket, which corresponds to the entry for a ‘Holy water bucket in gilded silver in the Renaissance style’, in an 1858 inventory of the King’s property in the Palácio das Necessidades.

This story reveals how clues on objects themselves spark research which can help us to uncover object histories. In this case, the engraved cypher, the 1882 exhibition catalogue, the photograph by Charles Thurston Thompson, and (vitally) the 2022 book by Hugo Xavier on the King’s 1866 inventory were the key elements that uncovered the 19th-century history of the holy water bucket. The King’s 1866 inventory notes it had been owned by an aristocratic Portuguese family; Xavier’s book also refers to a receipt in the archives of the dukes of Braganza that shows that the bucket was bought by King Fernando II in November 1850, along with silver-gilt salvers, ewers, a salt and a flask, from the goldsmith Raimundo José Pinto, who supplied pieces to the Royal Household. Pinto, in partnership with the goldsmith Estevão de Sousa, traded at ‘Casa Pinto & Sousa’, located in no. 1 and 2 of rua da Prata, near Praça do Comércio, in Lisbon. In another inventory, the Inventário Orfanológico, drawn up in 1885 for the division of assets after Fernando’s death, the holy water bucket appears as no. 2392. According to Hugo Xavier, it came into the possession of Antónia of Portugal, daughter of Dom Fernando II, and Princess of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, in 1892.

Just over a hundred years later, the holy water bucket was acquired by Sir Arthur Gilbert and his wife Rosalinde from the London dealer, Partridge, in 1994. The Gilberts formed one of the world’s great decorative art collections which Arthur donated to Britain in 1996. Since 2008 it has resided at the V&A. The new information that has been uncovered about the bucket’s journey from Burgos to London, via Lisbon, has shed new light on this precious object. The holy water bucket will feature in a forthcoming display as part of plans for a newly designed and expanded Gilbert galleries at the V&A, which will open its doors to visitors in 2025.

Can you explain the historical context of Portuguese royal silver in the Gilbert Collection?

It had a certain polish this article