By Ekta Raheja and Annabelle Camp

It is unusual – if not unknown – to find a historically complete ensemble in a museum collection. Imagine our excitement, then, when we encountered a 19th-century Rajput court ensemble in the South Asian collection at the V&A – not only complete but distinguished by an unusual pattern on the fabric! While the V&A holds plain white, solid-coloured, printed and embroidered jamas (skirted robes) in its collection, this ensemble has a unique and extraordinary flecked pattern in red dye applied all over the fine muslin. The spatter-pattern is used on the jama, the kurta (tunic) and the paijama (drawstring trousers) worn with it. The accompanying beard cloth, also flecked with the red dye, a red muslin kamarband (waist sash) and lapeta (decorative turban band), and splatter-patterned turban complete the ensemble. Silver-gilt gota (tinsel ribbon) borders define the various shapes of these hand-stitched garments.

The jama was a skirted robe worn by men in many regions of India roughly from the 1500s to late 1800s. Accompanied by a fitted paijama, a regal turban and kamarband, as well as jewels and accessories, the garment gave its wearer a distinctive aristocratic profile. This jama was made in Jodhpur in Rajasthan during the 19th century – the construction of the robe is characteristic of the style popular in certain Rajasthani courts in the 1800s. The double-breasted bodice has fastenings, on the left-hand side of the wearer’s body, on the shoulders and under the arms. Additional internal cords hold the inner panel at the armpit and waist to keep the front in place. The back is embellished with an applied gota flower. The long sleeves – as well as the voluminous and heavy skirt – are trimmed with gota and gota moti borders of varying widths.

Holi – a celebration of spring, colour and love

On closer examination of the jama we discovered that the cloth for the bodice was sprayed with the dye before constructing the jama, while the skirt was sprayed after the skirt panels were sewn together and gathered into a waist-band. The evidence of spattering happening both before and after the construction of different elements of the garment told us that the spatter was a deliberate pattern choice, but we didn’t initially understand its significance.

Further research revealed that the choice of spatter-patterning indicated the ensemble was designed as celebration wear for the Hindu festival of Holi. The spatter-pattern dye technique is worked by spraying a red dye on white, pale pink or yellow cotton and is locally known in Jodhpur and Jaipur as faganya or faguniya, named after the spring month of Phalgun (late February to early March) in which Holi is celebrated. The festival is celebrated throughout the Northern part of India, during which revellers throw gulal (coloured powder) and spray coloured water from pichkaris (syringes) on each other to rejoice in the arrival of spring. In Jaipur, the king, his family, courtiers and servants wore dresses of different colours and dye-print designs on various festivals and ceremonial occasions: tie-dye laharia on Teej; chuniri or plain red or green on Gangaur; faganya on Holi; black on Diwali; white or light pink, or motia, on Sharad Purnima and red with gold on the birthday of the ruler (see further Textiles and costumes from the Maharaja Sawai Singh II Museum, Chandramani Singh,Maharaja Sawai Singh II Museum Trust 1979).

In fact, from the 1600s to 1800s, the faganya dye-patterning technique was popularly used to decorate garments worn by not only the rulers of Jodhpur but rulers throughout Rajasthan. The same dye-patterning method, known as Chatma in Udaipur, can be seen in the eighteenth-century portrait of Maharana Amar Singh (1559 – 1620). The painting shows the Maharana wearing an ankle length jama made of white muslin, speckled with a red dye, suggesting he has been participating in the Holi festivities. However, few examples of this technique are known in Indian museum collections. As a result, we could find no research on the method used for the dye-patterning.

A pichkari or a paint brush?

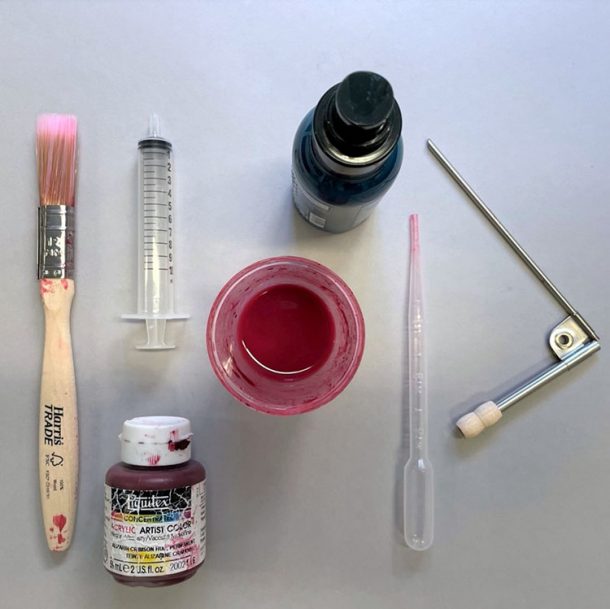

Determined to understand the technique, we collaborated to recreate the spattered pattern using rudimentary tools. We trialled six different application techniques using red-colored acrylic paint on cotton calico with a variety of tools including a syringe, pipette, fine tip filament brush, aerosol bottle, straw and an atomizer. We used acrylic paint to experiment, instead of dye, as it is nontoxic and fast drying.

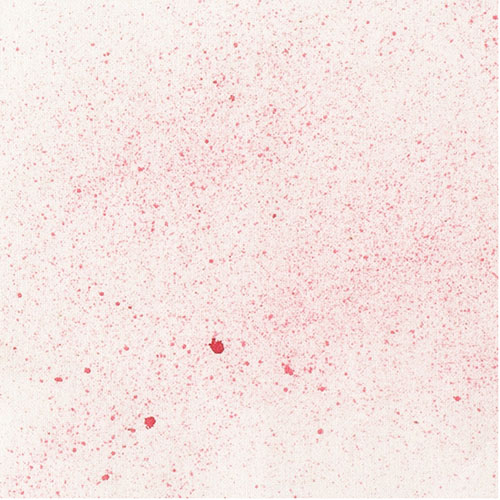

Sample result using a syringe – the lab-grade syringe has a similar mechanism to the pichkari used to spray coloured water during Holi. It resulted in a drip effect instead of a fine splatter.

Sample result using a pipette – the pipette, which uses partial vacuum to draw up and dispense liquid, provided a more controlled application. The results were similar to the drip produced by the syringe.

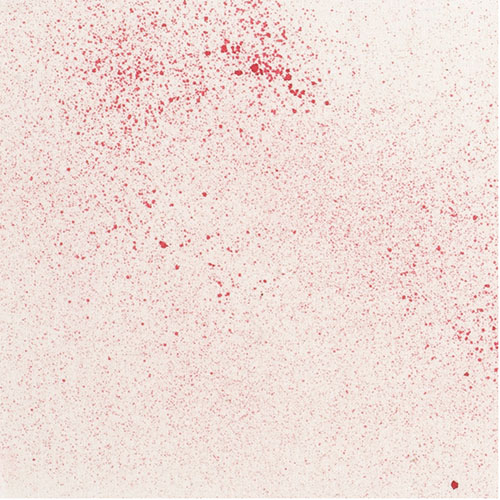

Sample result using a bristled tip brush – drawing from a childhood experience of painting in school in India, Ekta suggested a bristled paint brush. Flicking the brush dipped in paint with the thumb created a fine spatter on the cloth. This achieved a similar pattern to that seen on the original.

Sample result using an aerosol spray bottle – it is unlikely that this technology was available during the time. The result was fine mist, with rounder marks and a more regular pattern than the original.

Straw – instead of using the straw, as in blow painting, paint was lifted into the cavity and air was blown through it. This resulted in a blotchy pattern with very irregularly shaped marks.

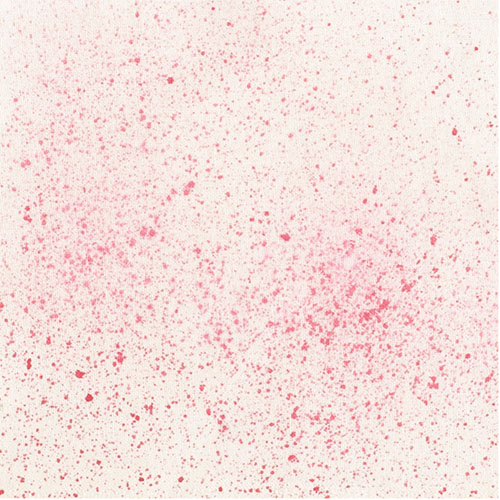

Sample result using a mouth atomizer – the atomizer is a rudimentary tool used by submerging the narrower tube end into paint and air is blown through the wider tube. It resulted in several layers of mist, creating a more solid wash instead of a distinct spatter.

The bristled brush produced the most compelling results. The fine spray is created by flicking the brush against a finger or a wooden dowel a few inches away from the fabric surface. We also tried the technique on a dry and wet surface. After analysing the several samples created, we concluded that a dry fabric surface was used to create the pattern on the jama.

While a pattern or dye would never be reapplied to a historic textile, trying to recreate the pattern or reconstruct the technique on sample material can provide us with a valuable understanding of the object and the tools and techniques used to make it. The use of reconstructions to better understand an object’s production is common in other areas of conservation, such as in paintings. However, it is rarely done in the study and conservation of textiles. The reconstruction highlighted the fine workmanship of the craftsman and need for patience and precision while printing on the cloth. Even though the technique is relatively simple, it is important to remember how evenly it is applied to the textiles and the incredibly large quantity of fabric to which it was applied. By gaining a better understanding of the dye application, we not only shed light on an unstudied technique; we also gain greater appreciation for the time and craftsmanship that went into the ensemble’s creation.

Learn more about the provenance of the spattered jama here. You can read more about the conservation of the jama carried out by Annabelle Camp as part of her work placement at the V&A for the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation here.