This is the V&A’s fourth special project with La Biennale di Venezia for the Pavilion of Applied Arts at the Venice Architecture Biennale. In response to Scottish-Ghanaian architect Lesley Lokko’s theme, ‘The Laboratory of the Future’, which she intends specifically to refer to Africa, the V&A have exhibited Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Power in West Africa.

The pavilion explores Tropical Modernism, the architectural style that adapted an international modernist aesthetic to the hot, humid conditions of the region. Though a colonial imposition in British West Africa, with buildings paid for out of the Colonial Office’s £200m (£6 billion today) post-war fund to modernise the colonies and strengthen ties to the Metropolis, the style survived the transition to Independence, when it became a key aspect of nation-building and symbol of the progressiveness and internationalism of these new countries.

The pavilion is the result of a five-year research partnership with the Architectural Association (AA), which started an influential Department of Tropical Architecture in 1954, and Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Kumasi, Ghana, where the AA started an outpost a decade later. This research will inform an exhibition at the V&A in South Kensington on Tropical Modernism to open next year.

With my co-curators, Nana Biamah-Ofosu and Bushra Mohamed from the AA, we deliberately set out to complicate the history of Tropical Modernism by engaging with and centring African perspectives. In the V&A’s Architecture Gallery there are currently no Africa-related exhibits. In looking at the process of decolonisation through an architectural lens, we also hope to refresh the museum’s collection and practices.

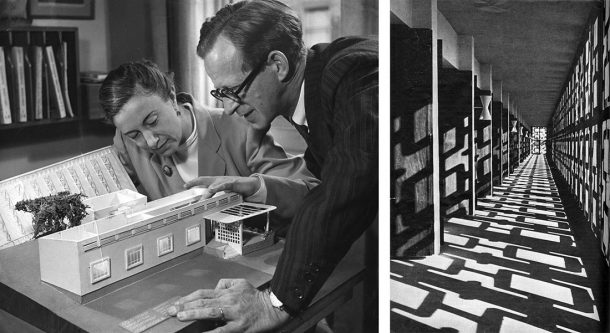

In the late 1940s, in the context of British West Africa (Ghana, Nigeria, Gambia and Sierra Leone), British architects Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew developed the tools of Tropical Modernism. Rapid development made the region an experimental laboratory for colonial architects, presenting them with opportunities and commissions they would not have had in Britain. The couple’s distinctive scientifically-informed language of climate control – adjustable louvers, wide eaves and brises soleils that mitigated against the tropical climate – attracted international attention.

They propagated it through their influential book, Tropical Architecture (1956) and the Department of Tropical Architecture they established in 1954 at the Architectural Association (AA), where they taught European architects to work in the colonies. Tropical Modernism in West Africa was designed to provide comfort, mainly to colonial administrators, and Fry and Drew’s schools and other public buildings were intended to create a more productive colonial subject and offset calls for independence.

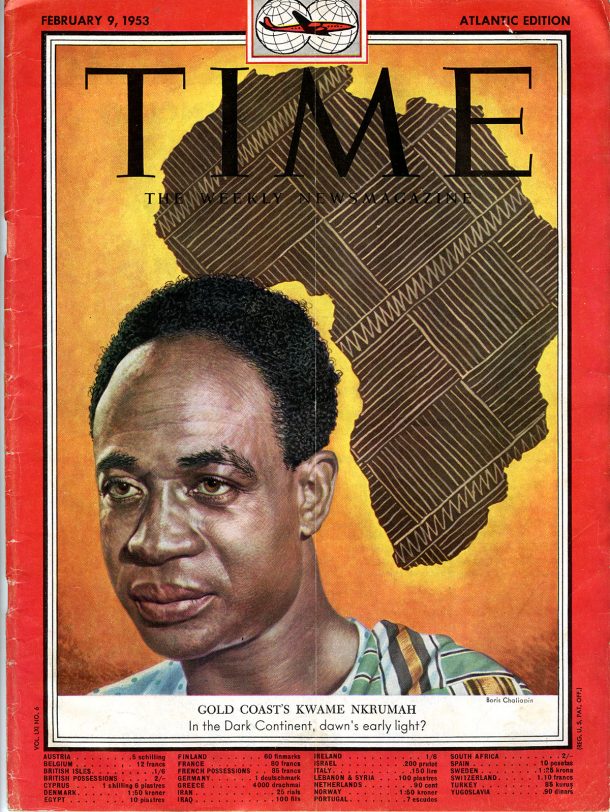

Tropical Modernism was developed against the backdrop of political unrest and decolonial struggle. In 1947, Kwame Nkrumah returned to the Gold Coast from London and implemented a campaign of ‘Positive Action’ inspired by Gandhi. In response to boycotts, strikes and riots, buildings were sometimes commissioned by the colonists and western corporations as propagandistic gifts. Fry and Drew’s Community Centre, commissioned by the United African Corporation after their headquarters was burned down in the Accra riots of 1948, was one such deliberate tool of attempted pacification.

In 1957, Ghana was the first country south of the Sahara to gain independence and Kwame Nkrumah became the country’s first Prime Minister and then President. Over the next decade the so-called ‘winds of change’ would sweep across Africa and 32 countries – two-thirds of the continent – won independence. Nkrumah saw in Tropical Modernism the possibility not only for nation-building, but an expression of his Pan-African ideology, which sought to make meaningful links between all of Africa and its diaspora.

He thought that the Independence of Ghana was meaningless unless linked to the liberation of all Africa (‘Africa must unite or perish!’, he said), and commissioned architects from Eastern Europe to work alongside newly trained Ghanaian architects to create monumental structures that were intended as beacons for a free Africa. These included Black Star Gate, a huge double arch framing the sea built as the centrepiece of Independence Square to celebrate Ghana becoming a Republic.

It was designed as an arch of return, the opposite of the ‘door of no return’ in the colonial forts through which so many Africans were forced as part of the transatlantic slave trade. Nkrumah encouraged the African diaspora to come back and help liberate and rebuild Africa. Sitting on the gate’s balcony, overlooking the square from under a huge umbrella, a symbol of chiefly power, he positioned himself as the leader of what he hoped would be a United States of Africa.

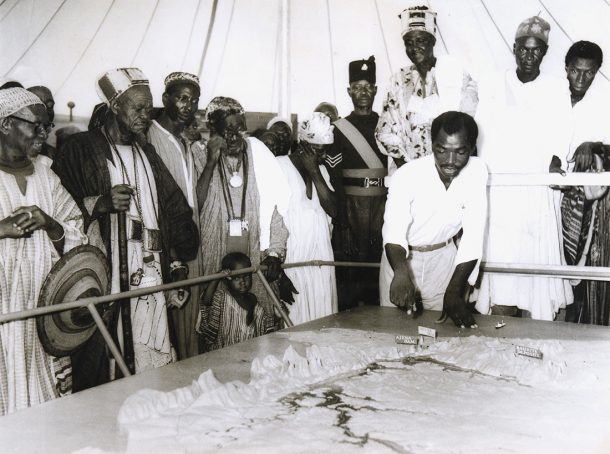

Nkrumah persuaded Harvard-trained architect Victor Adegbite to return to Ghana from the United States to become the country’s Chief Architect. Under Nkrumah’s indigenisation or Africanisation policy, Ghanaian architects were required partners on all construction projects, and they worked on a spate of school, hospital and infrastructure projects including the Volta hydroelectric dam, which Nkrumah hoped would power the country’s ambitious industrial and social strategy.

As an important part of this political policy, the training programme between Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Kumasi and the AA was set up. John Lloyd, who had no previous experience of the tropics, was sent by the AA to head up the Kumasi school. Whereas Fry and Drew had seen to learn from traditional African architecture, Lloyd showed a new appreciation of cultural context and instituted a course in its history.

KNUST became something of a Bauhaus in the tropics. Lloyd invited luminaries such as Buckminster Fuller to Kumasi to teach, and students made a series of geodesic domes, including a huge structure at Ghana’s first International Trade Fair in 1967 to house university exhibits. Lloyd also hired Ghanaian teachers like John Owusu Addo, who was sent to the AA for training at the Tropical School, and Max Bond, an African American architect who had trained at Harvard and came to Ghana at Nkrumah’s invitation.

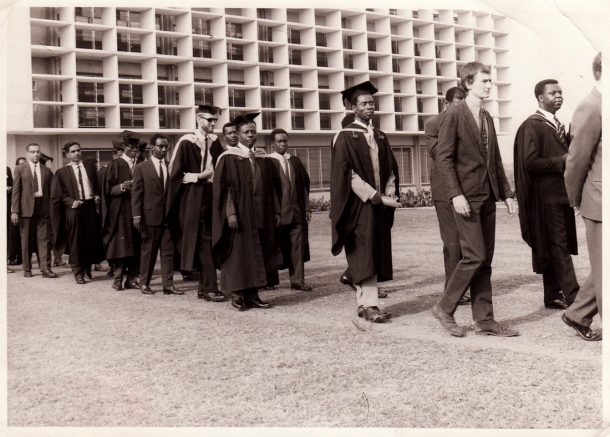

Addo and Bond argued that the post-colonial architect ‘must assume a broader place in society, as consolidators, innovators, propogandists, activists, as well as designers’ and self-consciously adapted Tropical Modernism to incorporate traditional Ghanaianelements, not to imitate the past but to create a new fusion for the future. KNUST’s campus became something of a laboratory for this Africanisation of architecture.

We’ve been tracking down former students and staff that were part of this institutional exchange and went on to play key roles in the development of modern architecture in West Africa but who are too often overlooked in the archives. Through an analysis of institutional registers at the AA, KNUST, RIBA and the Ghana and Nigerian Institute of Architects, and using our wider networks, we’ve been able to name and celebrate some of those that have been overlooked.

The Pavilion of Applied Arts is an atmospheric space with a long corridor and a main volume that is a labyrinth of brick pillars. We made use of the elongated plan by constructing a 36-metre-long brise soleil wall, loosely modelled on one that Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew built for the University of Ibadan in Nigeria. Its apertures house a series of embedded lightboxes, a display idea that came from the stained-glass galleries at the V&A. They contain photographs and other archival ephemera that tell the story of Tropical Modernism against the politics of the time.

This introductory section introduces a 28-minute-long film shown on three screens in the main volume of the pavilion, a cinema space cordoned off with heavy material in the colours of Marcus Garvey’s Pan-African flag. The film includes panoramic footage of 16 key buildings that we filmed in Accra, Cape Coast and Kumasi earlier this year. To provide context from the time, they are edited together with newsreel archive and 8mm home movie footage found in the attic of the late historian Hugh Thomas, whose father lived and worked in Ghana in the 1950s and 60s, with intimate access to Nkrumah.

The film also features interviews we conducted in Ghana, including with 95-year-old John Owusu Addo, one of Ghana’s first qualified architects, who trained at the AA and built many buildings at KNUST, and Henry Wellington, who was also sent to the AA when a KNUST student. Nkrumah’s daughter, Samia, discusses her father’s rise to power and dramatic fall, and Ola Uduku, Professor of Architecture at the University of Liverpool, explains how architecture was used as a deliberate instrument of control in late colonial Ghana and as a symbol of freedom after Independence.

In 1966, after an optimistic start, Nkrumah – who a couple of years earlier had declared Ghana a one-party state and imprisoned his political opponents – was overthrown in a military coup. Nkrumah subsequently lived in exile in Guinea, where he had the honorary title of Co-President, and he died in 1972. Some of the statues of Nkrumah (many by Italian sculptor Nicola Cataudella) that were toppled and dismembered in the coup, have been mounted on new plinths as part of a recent rehabilitation of his legacy.

At around the time of the coup, Tropical Modernism began a slow decline, its principles of climate control made redundant above all by the air-conditioning unit. The open, perforated facades of Tropical Modernism, which facilitated cross-ventilation, were entombed in glass. But, we ask in the exhibition, as we face an era of climate change, can Tropical Modernism’s scientifically-informed principles of passive cooling be re-examined? And can significant examples of Tropical Modernism – with many important buildings currently at risk from development and decay – be revalued and saved?

The 18th International Architecture Exhibition, curated by Lesley Lokko, will be open from Saturday 20 May to Sunday 26 November. The V&A/La Biennale Special Project, Tropical Modernism: Architecture and Power in West Africa (curated by Christopher Turner, Nana Biamah-Ofosu and Bushra Mohamed) is on view at the Pavilion of Applied Arts in the Arsenale.

Dear Christopher,

Connecting on behalf of The Architecture Club. We’d love to have a curator-led tour of your Tropical Modernism exhibition, if possible.

Would you kindly let me know how to request this formally?

Best wishes,

Jonathan

jonathan@propelling-pencil.com