As this week is National Gardening Week in the UK it seems a good time to consider gardening as an inspirational source of subject matter within the world of illustrated books. More specifically we’ll take a look at the V&A’s rich holdings in Victorian and turn of the century children’s books on this subject matter.

Beatrix Potter (1866 – 1943), like many young ladies of her class and era, was inspired to copy flowers and plants, referring to manuals such as John E. Sowerby’s British Wild Flowers (1858-1860), and Vere Foster’s drawing manuals. The results of Potter’s work are magnificent and contributed to provide the rich tapestry of backgrounds inhabited by identifiable flowers for her ‘little books’.

These beautiful drawing manuals are often referred to, but what stories and non-fiction about gardening itself as a pastime existed for children during the 19th century? How was gardening “sold” to children as a concept during this age when careful copying of details under the microscope became possible for the middle-class enthusiast and amateur botany a popular pastime?

In 1830 – so just before the Victorian era – Catechism of Horticulture, part of A Perfect Juvenile Cyclopaedia by Whittaker and Co. was published. This publication demonstrates a popular way of appealing to a younger audience by producing page after page of question and answers on the subject!

The catechism format of question and answer has a long history which began with Christian teachings of the New Testament. With time this format began to broach more secular pursuits, such as gardening.

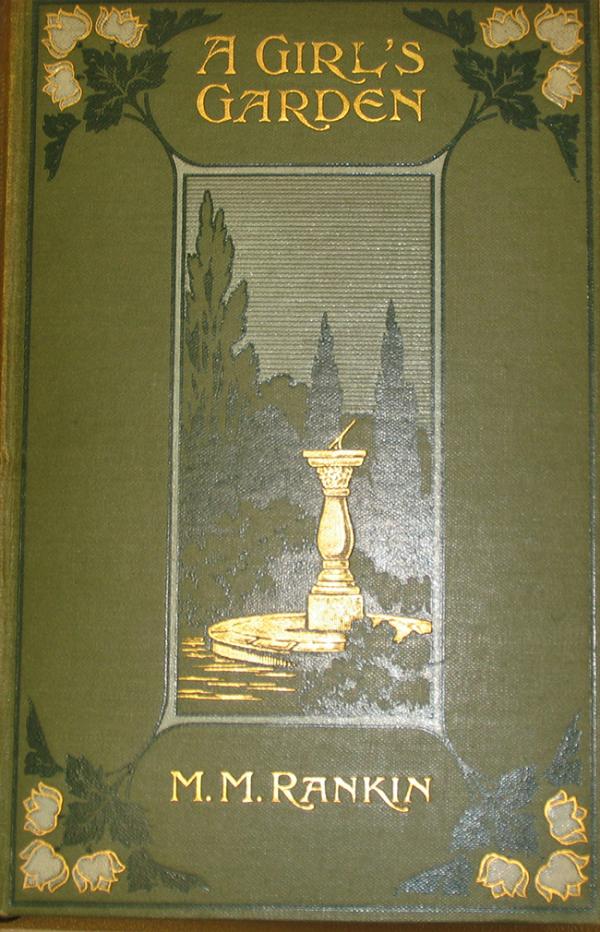

Ploughing forward into Edwardian Britain we can take a look at A Girl’s Garden by M. M. Rankin, 1905. We immediately see an Art Nouveau influenced cover and title page that in fact conceal a less lavish interior to the book with black and white half tone illustrations. However, the structure of the book presents a considered and appealing journey through the months and is one that a younger reader could dip into to inform their knowledge of gardening activities possible for a certain time of year.

We can end our journey by considering how these books contributed to a literary climate that helped inspire the seminal piece of enchanting children’s literature, The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett, at the end of the Edwardian period in 1910.

View further information relating to Beatrix Potter’s studies of the natural world. And don’t forget that a variety of topic boxes can be viewed of Potter’s art work as well as the children’s literature collections by booking an appointment at the Blythe House Reading Room.