The Military Buff coat: A haptic experience

During my time as an MA student on the V&A/RCA History of Design course I came across a word, haptic, that has fascinated me ever since. Both its sound when spoken and its meaning have resonated with me since I first heard the word and has often shaped my thoughts about objects around me. In particular the many different haptic experiences one person can have wearing different types of clothes.

Haptics is any form of nonverbal communication involving touch. Haptic experience then in relation to clothing is the nonverbal experience of the materiality of the clothing worn on the body. The feel of different fabrics, their weight, the different ways that they enclose and reveal the body, the way that materials we wear on our bodies protect or leave us vulnerable to the world around us. During my research for my MA dissertation on the development of English military uniform between 1645-1708, I stumbled across an object, a piece of clothing, for which this notion of haptic experience struck me as being particularly important and illuminating, the leather buff coat.

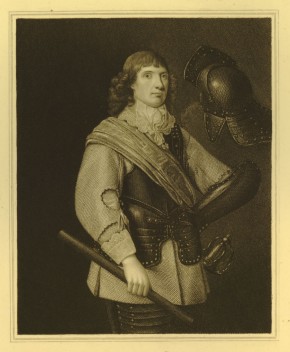

The leather buff coat was worn mostly by military men of senior rank or by those in the cavalry throughout most of the 17th century. It has always been a closely fitted jacket with full skirts open at the front and the sides and a further one up the back to allow for easy movement and to sit comfortably on a horse.

The buff coat in England was a garment made from thick cowhides. The front is always open and every coat I have come across in my research has a row of holes down each side of the opening of the coat, which would have had lacing so that when the coat was done up with hooks and eyes it would look as if the coat was laced.

It was a thick, heavy and rough item of clothing that through constant use in battle, inclement weather and every other harsh military condition would become very stiff and develop a sour smell.1 Despite this, the act of wearing this item of clothing gave a sense of pride and authority to the wearer. Its very construction, thickness (up to half an inch in some cases) and weight compared to the regular soldiers thinner woollen coat showed the superiority of the garment, evoking for the individual clothed in this strong and heavy coat, a feeling of protection encouraging the wearer to walk taller and potentially fight with more bravery and force.

The construction of the coat itself would have enforced a certain stance and way of movement. The curved arms would have made it easier to hold the reins of a horse, the straight back and lacing at the front would have promoted good posture and the large open flaps for easy leg movement would have allowed the wearer to move quickly and easily which is essential on the battlefield if thrown from your horse. More importantly when worn over an extended period of time both the coat and wearer would start to blend their shapes together influencing one another. What is particularly noticeable about the Littlecote armouries collection of thirty four buff coats now held at the Royal Armouries in Leeds, is that nearly all the buff coats are signed in the collar, one seems to have the name Mainwaring handwritten in it another has the initials P.B.

This practice further illustrates that the wearer of a particular buff coat was inextricably linked to that particular coat, it was an expensive item that was long lasting and for a cavalry soldier when paid off through their off-reckonings it could be worn in civilian society to represent their identity as a soldier, their strength and as a mark of their military valour.2

Of course depending on the price paid for one of these coats you could get very different quality garments and consequently the haptic experience of wearing this item of clothing would be very different. For those that could spend up to £10 for a buff coat you could get a uniquely designed, beautifully crafted, thick coat that could help to protect against glancing sword blows, indeed many of the surviving coats that belonged to senior officers show evidence of just this.3 If however, you paid less than a £1 for your buff coat you would most likely get a coat made from thin hides of a standardised form that would offer very little physical protection in battle.4 Of course unlike armour a direct hit with either sword or bullet rendered the coats protection useless as can be seen in King Gustavus Adolphus’ buff coat in Sweden in which he was killed.

I will conclude by saying something about what we learn by thinking through the haptic experience of wearing an item of clothing. We can try to imagine the movement/restrictions, the feel of the material, texture, smell, weight, which coupled with research and knowledge of an objects context and history can reveal much more about the particular individual or type of person that would have worn the garment. This kind of thinking can help to inform about environment, circumstances and importantly in the case of the buff coat how through the experience of wearing a particular garment can help to promote and encourage particular behaviour.

Footnotes

1. I was fortunate enough to talk this through with a conservator at the National Army Museum who was in the process of conserving one of their buff coats for the ‘War Horse’ Exhibition, November 2011-2012.

2. John Tincey, The British Army 1660-1704 (London: Osprey, 1994), p. 18.

3. National Archives, Warrants (1662), SP 44/7.

4. National Archives, Commonwealth Exchequer Papers (1642-1649), SP 28/127 &135.

I found this article fascinating; thank you!

One note, though: Gustav Adolph was killed by a gun-shot, NOT a sword blow. The hole we see is where the shot entered.

Many thanks for bringing this mistake to my attention I have now corrected this in the post.

Thanks for the great article, I understnad the thinkness of the leather did vary. Is there a typical, average thinkness you came across?

When we were doing 17th century reenactment, we spent a lot of time lacing up those damned coats.Then we found out about the hooks and eyes. Apparently, hooks and eyes were not universal, as Gustavus Adolphus’s buff coat did lace up.

Thank you super article – I have a thin m/c sewn reproduction which I am going to deconstruct to make a pattern. I have purchased some 5mm buff leather which I will butt stitch in an attempt to recreate an authetic replica – I will keep an account of the time taken, which may explain the cost of an original!