This is a guest blog by Prof Sabine Frommel, Director of Studies, Art History of the Renaissance, École Pratique des Hautes Études, PSL, Sorbonne (Section of Historical and Philological Studies), one of the international partners of the Architectural Models in Context Research Network, funded by the AHRC and based at the V&A.

An important objective of the history of art and architecture is to deepen knowledge of the processes of artistic conception and creation. Models assume a significant role in understanding the genesis of architectural projects during the Renaissance and invite interdisciplinary research.

Models or three-dimensional simulations underwent considerable development in the fifteenth century in Florence, where the most famous architects had been formed as legnaioli – joiners and carpenters – who were experienced in woodworking. Their design methods owed a great deal to the wooden models, which they developed during the design-phase and on the worksite. For instance Giuliano da Sangallo, one of the main representatives of this tradition, made material models of his drawings, not only to illustrate a design to his clients, but also when he needed to give his labourers the most accurate directions possible for the often complex implementation of his formal and technical solutions.

The city-state governed by rich families of merchants and bankers, and by prosperous guilds investing money in architecture, requested accurate and persuasive models of future buildings. The Medici used them also for diplomatic reasons to show cultural superiority through models of spectacular projects for the Aragona, for instance.

During the revolutionary metamorphosis of building types and architectural language in the Renaissance, the model helped to elaborate new solutions that reconciled local tradition and classical prototypes. The model fulfilled many functions and constituted first of all a tool for conception, where simple materials or vegetables (Antonio Manetti) served to simulate the structures. They could also have an empirical character, such as the cupola of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence which Filippo Brunelleschi used to check if the new type of construction was really self-supporting. On the building-site a large number of models were used, from general ones to those in real scale (1:1) for details. These models were legally binding.

The model of Palazzo Strozzi, the only one of a private building conserved from the fifteenth century, could be disassembled to view the interior spaces of the different stories. On its wooden surfaces were carved corrections or alternative solutions and some of these were adopted into the building. A model was appreciated as a subtle tool, which perpetually invited innovation, whose aesthetic and spatial impact was immediately controllable, much more so than in drawing which was used simultaneously. Parts and pieces of models were reused and contributed to the continuity and survival of architectural patterns.

Elegant models at a large scale assumed also a representative and even political function; often they were displayed in palaces and residences where they testified to prosperity, welfare, ideas and new visions. Their public presentation could take place as a grandiose performance. Ephemeral art during triumphal entries, ceremonies (princely and religious) and festive banquets provided an important field for experimentation and a significant number of models done for these occasions stimulated monumental projects.

Models thus played an important role in the migration and circulation of ideas, knowledge and architectural forms in Europe. The wonderful classicizing details of the castle of Ancy-le-Franc in Burgundy, made by French masters, required largescale models that were delivered by the Italian architect Sebastiano Serlio. Nevertheless, their transport remained difficult and, when arriving partly destroyed, they often provoked misunderstandings of classical syntax.

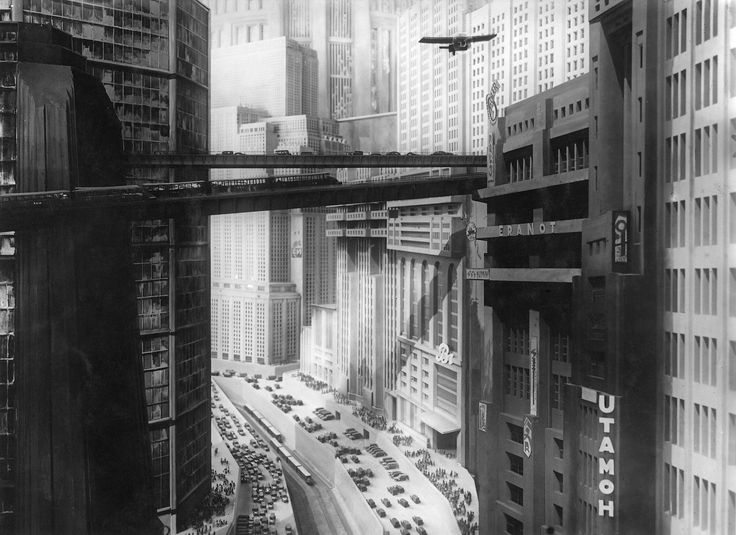

Such ephemeral art of the past can be compared to the models used by today’s film industry to produce persuasive simulations of towns, buildings and rooms (Metropolis of Fritz Lang or Shining of Stanley Kubrick). These models, which proceed not by integral features but by singular pieces, accordingly to a “pars pro toto”, are able to reinforce the narrative effect of the fiction. They provide an opportunity for interactions with built architecture that may prove visionary and influential for future towns and buildings.

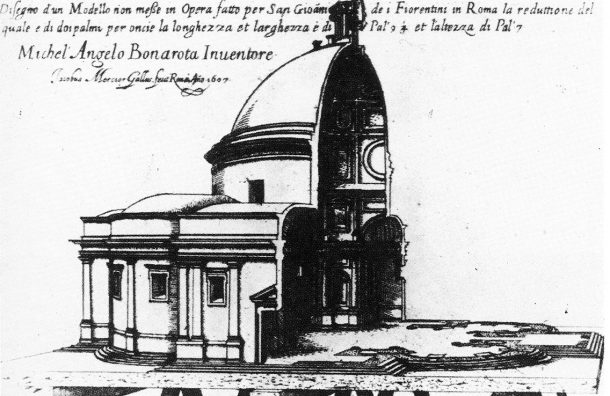

Models that were conserved in churches, palaces or public buildings had a Nachleben that is almost unstudied. In some cases, they were surveyed by historians or architects (the model of Michelangelo’s project of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini by the French Jacques le Mercier or those of the castle of Chambord in France by André Félibien).

A lot of painted architectural representations seem connected to architectural models, perhaps some were even executed by painter-architects themselves (Perugino, Raphael) because it was easier to assimilate models into an illusionistic space than drawings.

Furthermore paintings, intarsia and sculptural works, often represent such models in liturgical art like tabernacles or sacrament houses and sometimes in idealised painted buildings. In this way, architectural models were especially significant in the renewal of architecture during the Renaissance.