‘We must … wash our hands with soap and hot water for the length of time it takes to sing Happy Birthday twice’... In 2020, facing a novel virus for which there is no vaccine, this is perhaps not the guidance we would have expected for how to act .

The humble bar of soap has acquired a new centrality in our lives during the pandemic. It is the first thing that we reach for when we enter our houses, hand-washing the first ritual that we undertake, cleansing ourselves of any contamination from the outside world. At a time of fear, uncertainty and devastating news headlines, soap’s new role of reassurance has seemed on the one hand surprising, almost ridiculous. How can this most common of commodities, made from a simple mix of fatty acids and an alkali, be the most effective weapon with which to arm ourselves? And yet, despite this seeming impossibility, we trust in it: we dutifully lather and scrub for 20 seconds, seeing in our mind’s eye soap’s protective barrier building around our hands, our bodies, our families and our homes, breaking the virus’s hold and protecting us from the potential perils of the world outside.

And yet, for all its commonality, soap is loaded with significance, as the V&A’s collections reveal. Not necessarily through holdings of soap itself, given its ephemerality – although there are novelty soaps in the shape of characters such as Muffin the Mule to be found in the Museum of Childhood’s collection – but in various forms of design. A late 17th-century spherical soap box, made from silver and engraved with a family crest, would have formed part of a larger toilette set, used by the most fashionable for their ablutions. 18th-century porcelain soap dishes, made by the Bow Porcelain Manufactory and decorated with blue and white painted flowers imitating Chinese porcelain, could only have been owned by the wealthiest, given the rarity and difficulty of producing porcelain at that time. Soap’s presence is there, but associated only with wealth and with fashion.

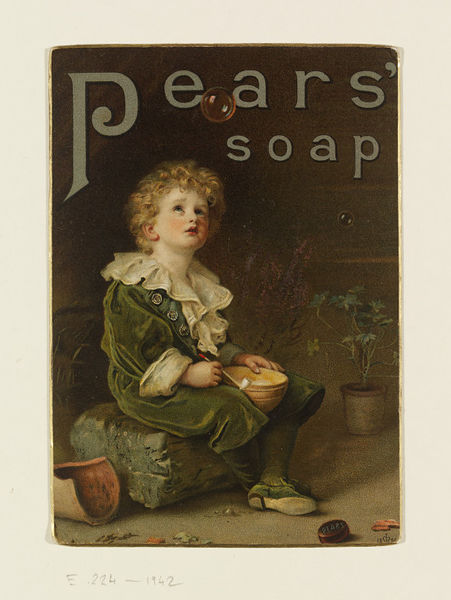

Fast-forward two centuries and the emphasis has changed: we find in our collections a plethora of late 19th – early 20th-century posters advertising the benefits and virtues of soaps produced by companies such as Pears, awarded the prize medal for soap at the Great Exhibition of 1851, and Lever Brothers (which would become Unilever), founded by William Hesketh Lever, later Viscount Leverhulme. Pears and Lever Brothers took similar approaches in marketing their products. Both acquired and adapted paintings by artists of the day to confer aesthetic status and respectability on their products, while also commissioning artists to produce boldly coloured graphic designs for posters that often featured wholesome children, beautiful women or whiter-than-white laundry accompanied by slogans such as ‘Pears soap: Matchless for the Complexion’, ‘Sunlight! Guarantee of purity’ and ‘Cleanliness is next to Godliness’.

But disturbing undercurrents belie these images. Pears, Lever and others aggressively marketed their soaps towards working class women in particular, seeking to expand their consumer bases by capitalising on growing public awareness of the links between hygiene and disease. By targeting health concerns and through their choice of marketing slogans and imagery, manufacturers persuaded consumers to discard the home- or locally-produced soaps that they had previously used, in favour of these new products that promised to make them healthier and more beautiful, their laundry whiter and easier to clean. But the reality behind those glossy white images was very different. Many people lived in highly unsanitary slum dwellings that lacked proper waste facilities or running water, while the industries selling them these dreams were built on the pillaging of natural resources – such as the mass harvesting of coconut oil in the Solomon Islands and the creation of vast palm oil plantations in the Congo – and the forced labour of colonised peoples.

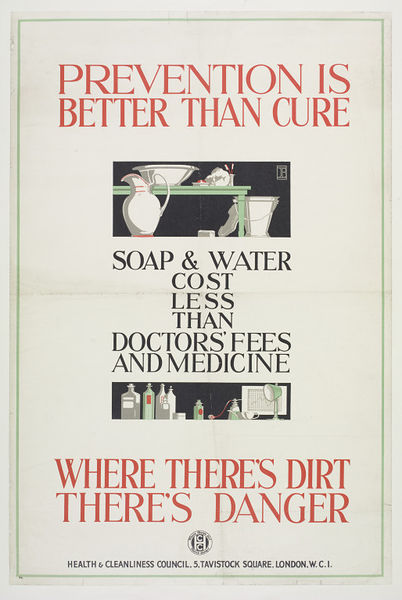

From today’s standpoint, one poster seems particularly striking. Issued by the Health & Cleanliness Council in around 1925, it reads ‘Prevention is better than cure…Where there’s dirt there’s danger’ but also reminds us, in a pre-NHS age, that ‘Soap & water cost less than doctors’ fees and medicine’. A century after this poster was produced, the guidance that we have been issued in the current pandemic is startlingly similar. But it also serves as a stark reminder of persisting inequalities that the virus is exacerbating in horrifying ways: the responsibility placed squarely on individuals for their own health, and yet the scale and shortage of the PPE that is really needed to protect against exposure to the virus. The horrifically disproportionate number of deaths suffered by members of BAME communities, including so many healthcare professionals. The lack of universal access to healthcare that makes handwashing even more important, and yet the lack of access to clean water that makes it an impossibility for many.

And suddenly, perhaps our bar of soap doesn’t seem so reassuring, after all.

Further reading:

‘Clean hands protect against infection’, World Health Organisation website infographic.

‘Why soap works’, New York Times, 13 March 2020.

Ann Stephen, ‘Selling soap: domestic work and consumption’, Labour History, no 61: Women, work and the labour movement in Australia and AoT, Nov 1991, pp57-69

The mass production of branded packaged goods emerged in concert with the mass media (most notably magazines) in the late 19th century, as part of the larger ecology of consumerism. The editorial content of such publications, especially those targeted at women, was highly educational and, be it said, funded by the advertisements. While it’s de rigueur to decry the inequity and offshoring of environmental and social expenses in the production of soap, it should also be noted that the hygiene message—in both advertisements and editorial content—had a profoundly positive effect on Western public health, in areas such as infant mortality.

Dear Joanna,

Your piece is great. Soap was the first thing that came to mind as a new painting project on getting stuck at home for months, with washing being a sudden and major preoccupation. I’ve spent three months painting soap and have not stopped yet. Please see my Instagram account @julietgoodden and website julietgoodden.org.

Thank you , Juliet