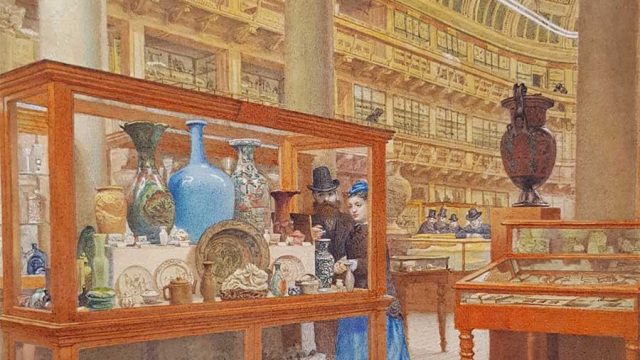

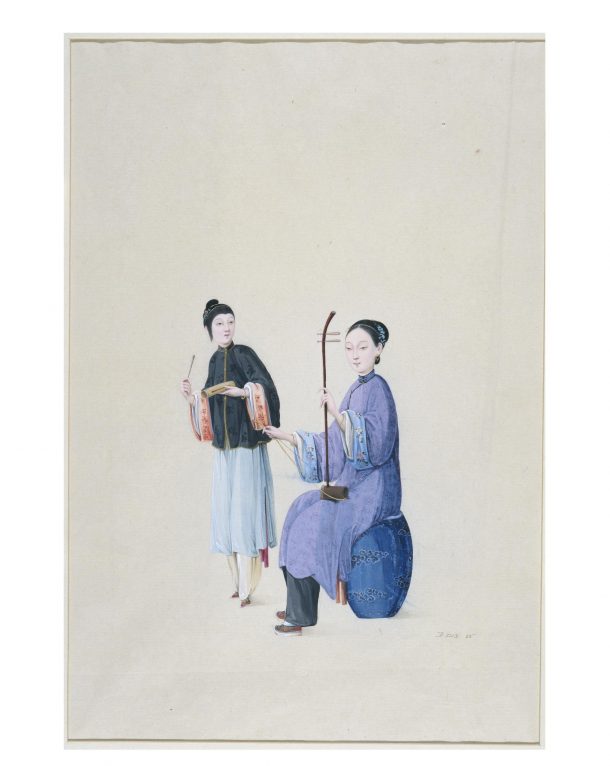

Musical instruments are complex and often composite objects, both decorative and functional. They are the result of historically regimented assemblages, with conflicting properties between material and acoustic qualities. Foremost, they are relational objects, geared towards the performer and the listener. These qualities are difficult to feature in museum situations, which means that visitors are often frustrated by looking at musical instruments in museums. At the time when museums become more theatrical, musical instruments – despite being among the most theatrical museum objects – are generally not part of this “slow morphing of museums into a stage” (Boris Groys).

To discuss these issues, in the light of the V&A’s own collections of musical instruments and their place in the museum’s history, VARI organized a creative interdisciplinary workshop entitled Searching for the New Sound : Creative Approaches to Musical, Instruments in Museum Collections. Encompassing a wide range of professional and disciplinary expertise, it brought together V&A curators and external museum colleagues, music producers, musicians, artists and academics.

Musical instruments share with other functional objects the fact that their use often generate emotional and physical relationships; but they differ by the nature of their function and thus of their “aura”, which is intangible and immaterial: they produce sound, which is vibration in the air. How then to capture this emotion, the magic of these tools, when their aim is invisible and difficult to represent – this has been the on-going question for all museums handling musical instruments collections.

Most visitors have, at least once in their lifetime, engaged with a flute, a piano or a guitar, whether at school, at home, with friends. How do they relate that personal and physical experience with the, almost, identical objects they can see (and only see) in the museum?

And how to retain the theatricality of these peculiar objects: instruments are always played on some kind of stage, even at home, where the object has its proper place. But the museum is a different kind of stage and therefore a new relation has to be found. Playing the instrument is of course one way of fulfilling the object’s ultimate goal; that of producing sound. It is an important one, and museums should thrive to play as much as possible, but museum objects are different from private instruments. They are meant to be transferred to future generations in the best possible condition, which playing inevitably harms. It is why specific conditions for playing have to be set. But playing is probably but one way of engaging with these instruments and new technological tools could help us finding others; for instance, we can already envisage that 3D digital visualization tools and virtual reality navigation processes could offer the visitor the possibility of manipulating objects, or their “avatar”, to touch them, or to play them virtually.

More general issues about sound in museums were raised, highlighting the role of architecture and the type of experience that the visitor encounters when sound in present. Are museums good sonic spaces? Generally not… How to use sound in galleries and exhibitions then? What type of concerts are truly appropriate? What kind of technology should we use for recorded sound? How about immersive situations, such as those that the V&A has provided in the David Bowie is; The Pink Floyd Exhibition and now Opera: Passion, Power, Politics exhibitions. How to deliver the same type of experience in permanent galleries? Are there other ways to provide sonic content? What if a whole gallery is considered as an instrument?

The outcome of these fascinating discussions brought thereby many more questions, which will feed into the V&A’s further discussions on the presence of sound in its future projects.

By, Eric de Visscher, Andrew W.Mellon Visiting Professor, VARI

Read Sound in Museums (1) by Eric here.

Listen to a recording of the Vaudry Harpsichord here.