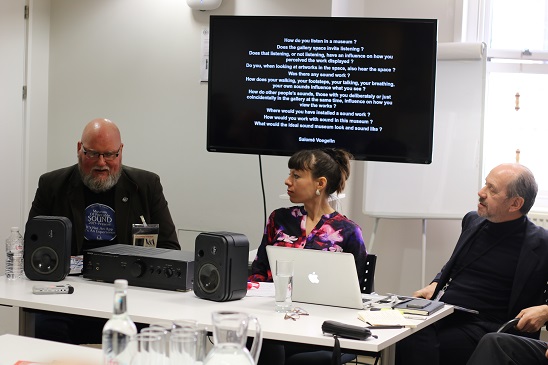

As part of my tenure at VARI, two interdisciplinary workshops were held, gathering V&A staff members and practitioners from various fields. These workshops, pointing towards the concept of the multisensory museum, took place in the context of the V&A’s own plans in East London and acknowledge the growing presence of sonic thinking in contemporary culture.

The first workshop, ‘Searching for the New Sound: Creative Approaches to Musical Instruments in Museum Collections,’ explored how the complex and multi-sensory aspects of musical instruments could be displayed in museums. It was all about their sound, but also about their haptic and physical qualities, and the ways in which the public could physically engage with these.

In the second workshop, entitled ‘Listening to the Museum : People, Places Objects. Aural Culture in the 21st-century Museum’, we adopted a broader lens, picking up two key, interlocked themes: museum architecture and sound; and museum collections and sound.

Again, the issue of physicality and embodied knowledge reappeared, both in the apprehension of aural architecture (« how do we perceive architecture through sound ?») and of sounding objects. And more broadly, we asked ourselves the question of how sound could inform us about objects and spaces : what do we learn from sound ? One of the conclusions of that seminar is that the study of sound and its uses in museums is to be seen in an interdisciplinary context.

Sound mixes historical study, design and histories of objects, the design of spaces, acoustical engineering, sound art and music, and participatory projects that invite a wider public to engage in the creation. We hear not only with our ears, but with all our senses, our knowledge and background, our relations to the others…

During the discussion, some of the participants suggested to think about « 10 Golden Rules » that museums should take into account when encountering sonic issues in their spaces, collections, exhibitions and events.

Here they are, as a way of raising questions and reactions :

- Museums are never silent: sound is present in museums as the result of the interaction between places and people, through sonorous artworks, or by hosting sonic events and performances. Consciously or not, “listening” is part of the museum experience: the term “audience” comes from the Latin verb audire (to listen).

- If museums are about “making connections with lived experiences”, then, for many visitors, especially younger ones, these experiences are now lived “in sound”, often through the use of portable devices.

- Museum architecture and design, for permanent buildings or temporary exhibitions, must take into account this ”Fourth Dimension”, not only from the acoustic point of view (noise levels, insulation), but as a “sonic philosophy” outlining visitor’s journeys.

- Sound plays a significant role in the interpretation of artworks, even silent ones, as part of the “multisensory” museum. “The longer we heard, the more we looked”.

- It is essential to define criteria on the use of sound in gallery spaces, to provide positive experiences and diminish senses of disturbances: “Why sound?” is an essential question that constantly needs to be addressed.

- Great care must be given to the right technological choice in order to deliver sound in the most appropriate way: this depends on content, context, sustainability and, or course, cost.

- When dealing with museum objects whose aim is to produce sound (musical instruments, clocks, radios, etc.), careful attention must be given on how to collect, preserve, exhibit the sonic aspects of these.

- If the functionality of those objects cannot be maintained for conservation purposes, every effort should be to made to provide access to it through other means: replicas, recordings, non-auditory methods, like literary or visual descriptions, etc.

- Sound should be treated as a museum object. This requires special training from museum staff: curators, conservators, technicians, gallery assistants,…

- Sound is particularly well-suited for the development of the “digital museum” and should be used as such in all possible ways.

By Eric de Visscher, Andrew W. Mellon Visiting Professor, VARI

Photographer for workshop: Eileen Budd

Nice post. I learn something totally new and challenging on websites I stumbleupon every day. It’s always useful to read through articles from other authors and practice something from other sites.