Through obvious or subtle ways, most objects suggest for whom they are meant. The intended users might be implied through an object’s scale, ease of use, the placement of particular parts of it, or cultural coding that could indicate certain professions, age groups, genders or abilities. The names of objects are important too, as with the speculum. This medical instrument is most typically used to dilate and hold open the vagina, usually in a medical setting. The word ‘speculum’ comes from the Latin verb specere ‘to look (at)’, indicating that this is an object concerned with seeing. The implied user of the speculum, as with other medical instruments, is usually the doctor or scientist who will operate it with their hand and look through it. But every medical device involves another user: the person to whose body it will be applied. When we explore the design history of the speculum, we can understand better how both those users are configured into the way such instruments work. The 3D-printed vaginal speculum attempts to disrupt the distance between the two users as it is intended as a DIY tool that can be made by anyone with access to a 3D printer rather than a specialist object that will only be utilised by a professional medic.

This printed version of the speculum is associated with GynePunk, a collective of feminist bio-hackers whose aim is to ‘decolonise gynaecology’. They equip those who feel disempowered by typical patient-doctor interactions, mainly through the dissemination of open-source instructions on how to create and use tools such as the speculum and histological equipment including a centrifuge, a microscope and an incubator that enable people to analyse their own body fluids at a molecular level. Through this work, they disrupt the way devices that are meant to be used by medical professionals tend to reside within a clinical setting; instead, GynePunk try to place these instruments in the hands of those whose bodies they are used on.

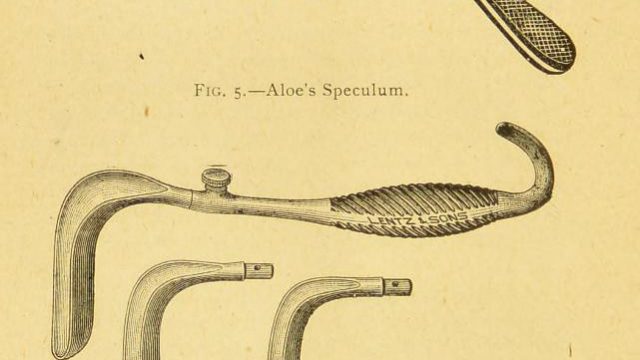

GynePunk are concerned with understanding how the often-violent history of sexual health has produced certain ways of studying bodies, not least through the speculum. One figure they reference in the violent use of the instrument is J. Marion Sims (1813–83), long described as the ‘father of modern gynaecology’. He invented a particular form of speculum as well as surgical techniques through years of often painful experimentation on enslaved women in pre-emancipation Alabama, USA, and commissioned the instrument that still bears his name from a silversmith, basing its form on a bent spoon that he had used in gynaecological exams. The u-shaped Sims speculum was designed to be used by a gynaecologist, but its optimum use depends on the examinee adopting a particular ‘Sims’ position’ to enable examination

While Sims and his acolytes described his speculum design as a breakthrough, other forms of specula have been in use for more than 2,000 years, as with this one from the Science Museum, London, that was excavated in Lebanon. Such ‘Roman’ type speculums most commonly involved protruding blades that could be opened internally, and more contemporary versions are very similar, but usually include a ‘site’ through which the user can look. As such, the form of the speculum is predicated on a function of vision. Despite the earlier precedents, these instruments only became widespread in the early modern period, and have been described by medical historians in relation to the gradual displacement of midwifery by male professional medics, and a shift in the expertise involved in birthing from knowing through touch to knowing through seeing, denoting the user as the one who looks.

The notorious history of the speculum is also associated with the Contagious Diseases Acts, first passed in 1864, which allowed for the mandatory vaginal examination of women suspected of ‘common prostitution’ in an attempt to stem the high rate of syphilis amongst soldiers and sailors throughout the British Empire. This focus on the use of the speculum as a diagnostic tool was scientifically dubious as the symptoms of syphilis could not easily be observed just by looking through the speculum, and those subject to the law testified to feeling brutalised and often injured by its use, indicating that the privileging of seeing in fact made the ostensible ‘usefulness’ of the instrument questionable.

While there have been some recent attempts to re-design the speculum to take into account the body it is being used on, commercial manufacturers still focus on what it affords those who are looking through it. In fact, one of the few domains where the sensation of the speculum on the body is fully considered as an important aspect of its use is in the register of kink, where medical grade speculums are advertised for sex play.

When we study the 3D-printed speculum, we’re seeing not an actual instrument that might be used for a medical exam, but a representation of a conventional instrument that is still configured for a user that both holds and looks through it. As such, it materialises not an ideal design for self-knowledge, but rather an aspiration that the violent history of its use be addressed, and perhaps the instrument be redesigned to account for users at both ends of the speculum.