Today, almost three weeks late, I present St. Barbara, another spurious Roman saint. She is said to have been born in the mid-3rd century, her father was wealthy, overbearing and pagan. He kept her locked in a tower to protect her from the world, but could not prevent her from secretly becoming a Christian and escaping to live a good (and clean) life in a bath house he had built. So enraged was he by her welcoming Jesus into her life, he tried to kill her with his sword. However, Barbara was able to escape through a hole which miraculously appeared in the wall, where she went to live in a gorge with some shepherds.

One of the shepherds betrayed her, causing him to be turned into stone and his flock into locusts. The Roman prefect of the place of her death (Heliopolis, Nicomedia, Tuscany and Rome all lay claim it) condemned her to be tortured, but she would not renounce her faith and her wounds would miraculously heal every night. Finally, her father volunteered to carry out her death sentence himself. After having concluded her short and difficult life, he was struck by lightning and killed on his way home.

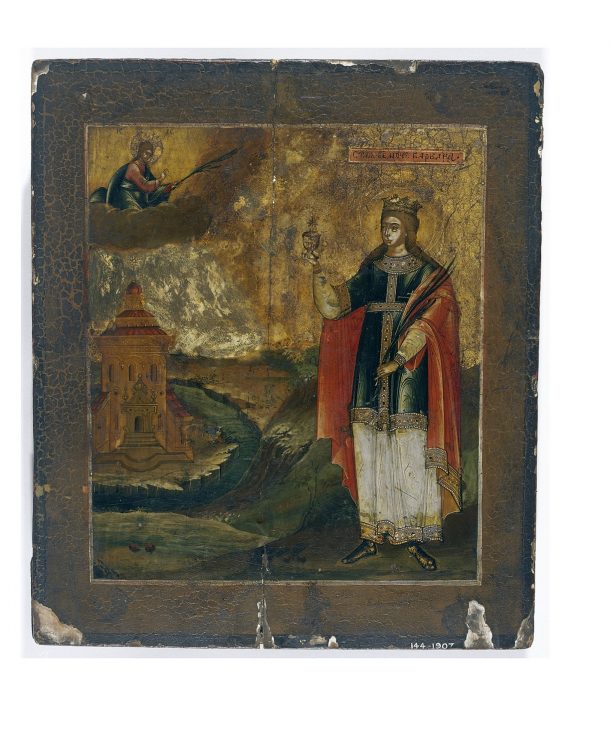

Barbara almost certainly is not a historic figure, her acts were not written until the 7th century and there is no evidence that she had an ancient cult. She became, though, a popular figure in medieval France. She is one of the crack team of 14 Holy Helpers and can be invoked against lightning, fire and sudden death. As such, she is a patron saint of firefighters and artillerymen, as well as prisoners. Her feast is celebrated on 4th December. She is usually depicted in art holding a tower and a martyr’s palm, sometimes trampling a heathen under foot.

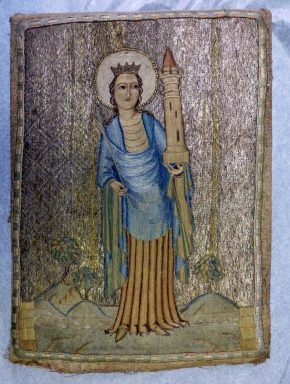

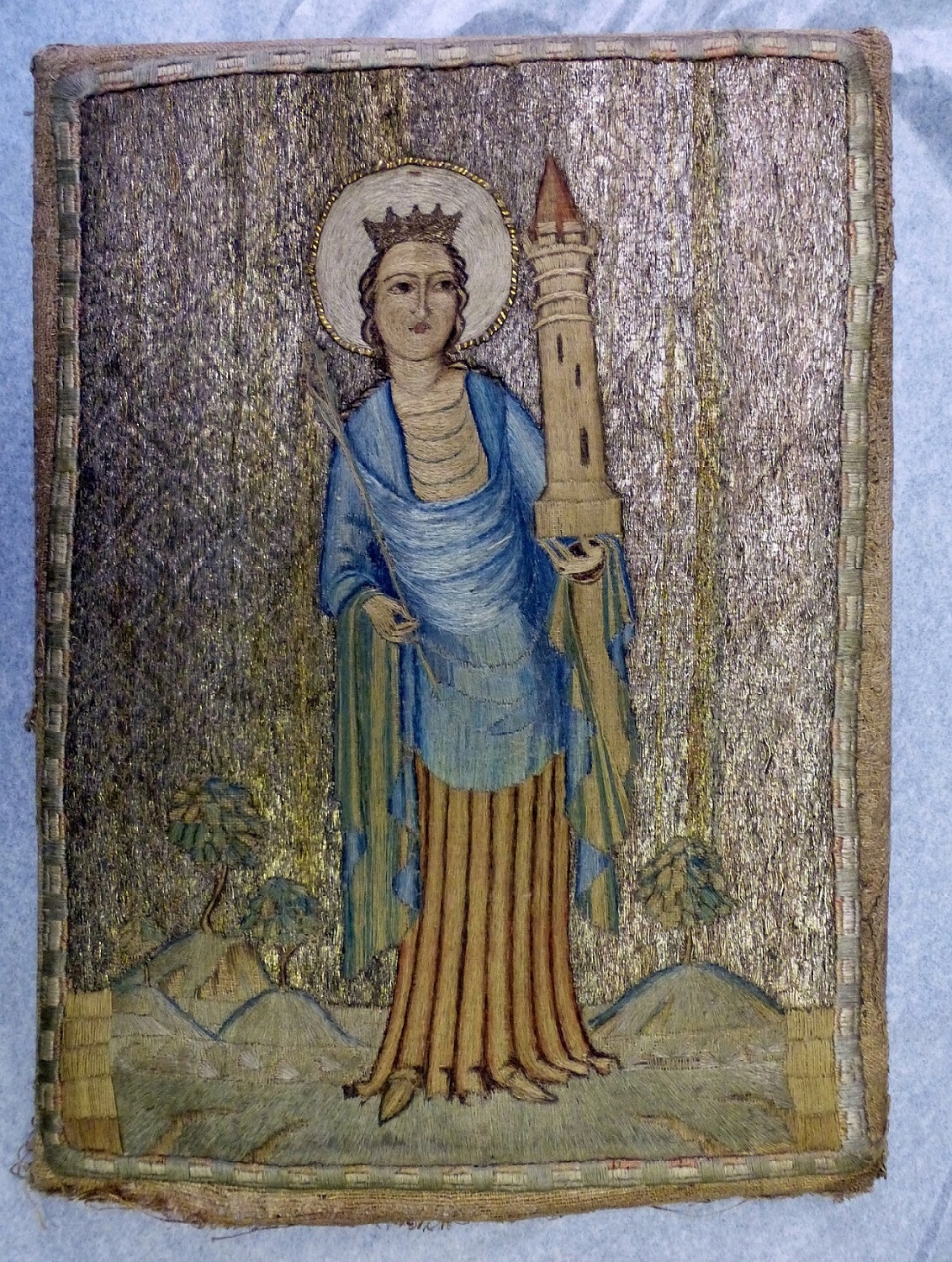

Evidence for her popularity is reflected in our collection, which features at least 35 objects depicting the saint. This one, an embroidered picture, is interesting for an offbeat reason, namely that it is probably a fake and the Museum may have been duped when it was purchased for the considerable sum of £90 in 1937. Initially, it was thought to date from the early 15th century, part of a group attributed to a closed convent in Cheb, Bohemia. However, following discussion in 1938-39, it was decided that the piece was almost certainly of modern production, owing in part to the presence of jute fibres in the canvas. Jute was not traded in Europe until the early 17th century. Colleagues from the Schlossmuseum in Kassel, and an independent conclusion made by curators at the Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio (who had received an Annunciation scene from the same group), confirmed the V&A’s fear that the piece was probably not genuine. Whoever it was that made it tried hard to make it look convincing, going so far as to interleave printed pages of Latin text between the wooden backing boards. Whatever would Holy Barbara have said?