Europe 1880–1914

Austria

In April 1897 a group of Vienna-based painters, sculptors and architects (led by painter Gustav Klimt) broke with the city's arts establishment, and formed an art movement called the Vienna Secession. Rejecting popular backwards-looking styles, the Secessionists made a point of connecting with the latest artistic movements abroad, including British Arts and Crafts. Inspired by the ideas of William Morris, the Secessionists wanted to reunite the fine and applied arts, and to use handmade goods to help rescue Austrian society from what they saw as the 'moral decay' of industrialisation. In 1900 the Vienna Secession invited artists from England, Scotland and France to take part in the group's 8th Exhibition, providing British Arts and Crafts with its first international platform.

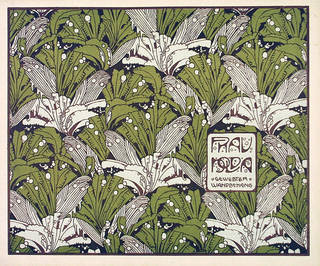

In 1902 two Secession members, architect Josef Hoffmann and artist Koloman Moser, formed the 'Wiener Werkstätte' (Vienna's Workshops) with the principal goal of 'bringing art into the home' via well-designed domestic products. Their model for this new venture was English designer Charles Robert Ashbee's Guild of Handicraft, which Hoffman had visited on a trip to London. Blending an Arts and Crafts-style commitment to traditional, high-quality production methods with a belief in forward-looking aesthetics, the Wiener Werkstätte produced benchmark designs in metalwork, furniture, glass, ceramics and textiles. Other important Vienna-based designers creating products for the home at this time include Josef Niedermoser and architects Otto Wagner and Adolf Loos.

Germany

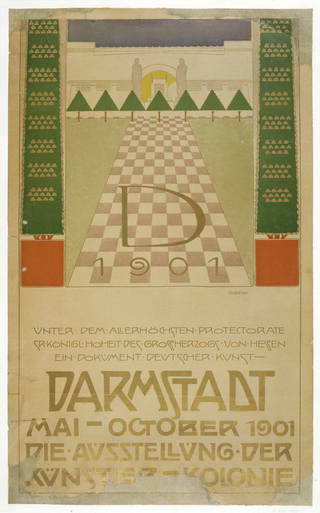

A number of German artists' colonies modelled themselves on British Arts and Crafts groups such as the Guild of Handicraft, the most well known being one at Darmstadt. Led by Austrian-born architect and designer Joseph Maria Olbrich, between 1901 and 1914 the project produced numerous examples of 'modern living culture' in the form of fully furnished private villas, apartments and workers' homes in Darmstadt's Mathildenhöhe district. The influence of British Arts and Crafts ideas about the importance of craft can also be seen in the work of designers such as Henry van de Velde, a Belgian-born architect, painter and interior designer whose work had a significant impact on German visual culture at the beginning of the 20th century.

In Germany, the model of production endorsed by British Arts and Crafts was generally thought to be too anti-industrial. The country's designers often saw technology as a legitimate means of achieving efficient production, as long as quality was maintained. For example, Richard Riemerschmid was influenced by Arts and Crafts ideas but at his United Workshops in Dresden, he developed designs for 'art furniture' that relied on production by machine. And in 1907 a group of influential designers set up an organisation based on a very pragmatic application of Arts and Crafts principles. The 'Deutscher Werkbund' (German Association of Craftsmen) aimed to improve the design of everyday domestic objects in collaboration with established large-scale producers – an idea realised by designs such as Peter Behrens' electric kettle for AEG (1908).

Scandinavia

In the Scandinavian countries during this period, greater political independence sparked nationalist feeling and debate about the need for new cultural identities. Even in more physically remote countries such as Finland and Norway, designers were able to follow developments in Britain and other parts of Europe. The Arts and Crafts model of craft and tradition combined with innovation, provided a framework in which individuals and the members of small workshops could create new and distinctive work. This revival of traditional handicrafts, however, still relied on the patronage of the upper-middle classes.

Silverware was particularly well supported, with Georg Jensen, a Dane, producing the most celebrated designs of the early 20th-century period. Similarly, Evald Nielsen, another Danish silversmith, upheld the principles of craft and quality in the production of his striking jewellery designs. In Finland, a new awareness of national identity (the country's territory remained part of the Russian Empire until 1917) found expression in the growth of design and the arts in general. A number of workshops produced radically modern designs, including the workshops in Porvoo, whose founder invited influential Brussels-educated English ceramicist Alfred William Finch to work there.

Russia

In Russia during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, severe social and economic deprivation co-existed with a desire to preserve the country's numerous and diverse local cultures. This led to the rediscovery of local vernacular (domestic and functional) architecture and design, and the assertion of national pride. Where British Arts and Crafts practitioners found the ideal style in designs from the medieval period, in central Europe the historical peasant village was the chief source of inspiration.

At the Abramtsevo Colony north of Moscow, artists worked to revive the high-quality traditions of the Russian decorative arts. Designers such as Viktor Hartman, Vasily Polenov, Viktor Vasnetsov and Yelena Polenova produced handmade furniture and tiles decorated with Russian imagery. This began a focus on regional themes that later expanded to include the production of drama and opera (with visits made by influential figures that included Konstantin Stanislavski and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov).

America: 1890–1916

Arts and Crafts societies and experimental communities, modelled on British examples, were first established in and around Massachusetts and New York in the early 1890s. American designers looked to their native heritage, landscape and climate, and their practice was generally more commercial than that of their European counterparts. Among the most notable of the East Coast designers to champion Arts and Crafts ideals was Gustav Stickley. Produced in his workshops in Syracuse, New York state, Stickley's designs reflected his belief in 'honesty, simplicity and usefulness', and the importance of creating reasonably priced pieces to furnish the homes of working people. This unadorned aesthetic became known as the 'Craftsman style', a look disseminated by The Craftsman, an influential magazine published by Stickley between 1901 and 1916.

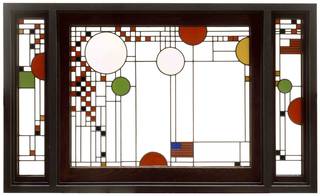

Arts and Crafts design was particularly influential in Chicago, which became a base for architects and designers of the 'Prairie School'. The flat landscape of the Midwest inspired Frank Lloyd Wright and his contemporaries to produce 'earth-hugging' domestic architecture that offered a radical alternative to the glass-and-steel aesthetic of Chicago's new skyscrapers. Lloyd Wright and his associates introduced revolutionary changes in domestic design. They opened up interiors, removed applied ornament and brought native plants into their design via abstract motifs. On the West Coast brothers Charles and Henry Greene, California's foremost Arts and Crafts architects and designers, treated the house as a 'total work of art'. Their furniture, notable for its exquisite joinery and use of sumptuous redwoods, was designed specifically to fit each room.

Japan: 1926 – end World War II

Led by the philosopher and critic Yanagi Sōetsu, the Mingei ('Folk Crafts') Movement in Japan was officially established in 1926. Equivalent to, and largely inspired by, the Arts and Crafts Movement in Britain, John Ruskin and William Morris were major influences. Mingei philosophy introduced the idea of 'direct perception', the intuitive ability to discover beauty that was 'born' rather than 'made'. Centred on the belief that humble goods could express fine aesthetic qualities, the movement advocated the use of historical folk crafts as a template for the production of domestic objects, assembling extensive collections of indigenous pieces. As well as collecting 'template' pieces, Mingei designers also created model rooms in an attempt to persuade the middle classes to adopt a new hybrid lifestyle that reflected Japan's rapidly modernising society by combining Japanese and western features.

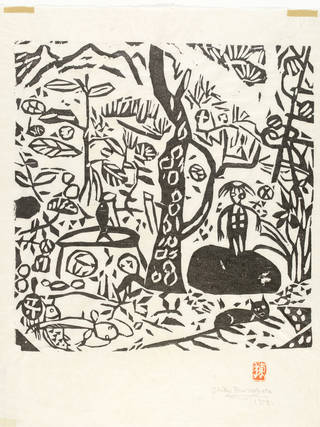

The Mingei Movement championed the work of named artist-craftsmen who, by example, helped to preserve and raise the standards of the kind of traditional artisanal craft production that was threatened by industrialisation. Four key figures in the development of the Movement were potters: the Englishman Bernard Leach, who lived in Japan from 1909 to 1920, Hamada Shōji (who set up the Leach Studio in St Ives, Cornwall with Bernard Leach in 1920), Kawai Kanjirō and Tomimoto Kenkichi; other notable designers include the textile artist Serizawa Keisuke, the woodwork and lacquer artist Kuroda Tatsuaki, and the painter and woodblock-print artist Munakata Shikō.

Discover more about Arts & Crafts.