The cover for Space Oddity, Bowie’s second album, features a photograph of Bowie's head overlaid on an optical spotted design by artist Victor Vasarely. Optical Art was popular in the 1960s and led to designs being printed on fabric and used in fashion. The abstract, futuristic feel of the blue spotted background chimes perfectly with Bowie’s space themed music and helped capture the zeitgeist of the time. The single, Space Oddity, was rush-released a few days before the moon landings, launching Bowie to stardom.

The title and subject of Space Oddity is said to have been influenced by William Anders' Earthrise, the first colour photograph of earth from space, taken in 1968. In 2003, Earthrise appeared in Life magazine's ‘100 Photographs that Changed the World’. Our collections include both a c-type photographic print of Earthrise and a screen print of Vasarely’s design, used on the cover of Space Oddity.

Over the years, Bowie worked with many prominent photographers. The V&A holds several images of him, from various stages in his career, but one of the most compelling is the portrait taken by Terry O’Neill in 1974. A potential cover for the Diamond Dogs album, the black and white image features David Bowie seated, wearing a hat and heeled boots. An open book lies facedown at his feet, while he holds onto a large white dog, standing on its hind legs.

In terms of Bowie’s career, O'Neill's shoot was transitional. It captured the sexually-ambiguous aura associated with Ziggy Stardust, but also anticipated the edgier energy that underpinned Bowie's period of working in the US and Berlin (1974 – 79). Though it wasn't used for its intended purpose as an album cover, the photograph showed the range of Bowie's creative networks, as well as the level of consideration applied to the making of his album sleeves.

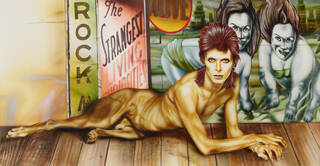

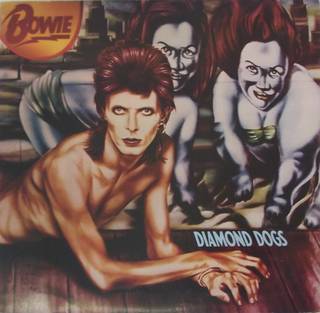

The final artwork for the Diamond Dogs gatefold sleeve was produced by Belgian illustrator Guy Peellaert, featuring Bowie as a hybrid human-dog. The V&A has two versions – the censored, in which the male genitalia is airbrushed, and the uncensored, which is now highly collectable. Pre-release publicity surrounding the uncensored artwork caused such controversy that all but a handful of the printed covers were scrapped, and replaced with a sensitively airbrushed version that then became commercially available.

In 1979, David Bowie began working with pop artist Derek Boshier for the creation of the cover of the Lodger album. Boshier then went on to design the cover of Let’s Dance in 1983, which became a global commercial success, generating more income than all of Bowie’s previous albums put together. Around the same time, Bowie asked Boshier to design a set for his 1983 Serious Moonlight tour. For this tour, Bowie intended to return to more theatrical presentation, moving on from the stark 1976 Isolar tour, with its minimalist set and Brechtian lighting.

The V&A's three-dimensional model of Boshier’s ambitious concept comprises geometric shapes of various sizes, painted in red, yellow, black and white glued to a base, while a cardboard cut-out musician leaps across the front of the stage playing a guitar. The fragmented design reflects Bowie’s request that Boshier come up with ‘something punky’, which ultimately proved too complicated for the likely venues and was replaced with a simpler lighting-based design from veteran stage designer Mark Ravitz.