Nature's beauty, diversity and power have been a rich source of inspiration for fashion for centuries. Today flowers, feathers and animal prints are rarely absent from the lists of seasonal trends. These fashions convey our shared delight and fascination with the natural world but they also tell a more nuanced story about how we interact with nature and our relationship with it.

Illustrated books, prints and, more recently, photographs and film, have always been a particularly rich source of imagery for textile and fashion designers. In medieval and Renaissance Europe, pattern designers took inspiration from bestiaries (books containing descriptions of real and imagined animals) and herbals (books containing descriptions of plants) and then, when the cultivation of ornamental gardens became popular in the 16th century, on florilegia (books that compile information on flowers, often accompanied by illustrations).

The establishment of physic gardens in the 1500s for the study of medicinal plants and botanical gardens (the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew in London is an 18th-century example) encouraged closer study and observation. Trade and exploration greatly helped with the collection of natural history specimens and led to a desire to order and categorise nature to understand how it functioned. It also helped to reveal how different species related not just to each other, but also to humans. A decorative fan in our collection is illustrated with drawings of the sexual anatomy of plants arranged according to Carl Linnaeus's classification system (1735). On the back of the fan the names of the flowers depicted on the front are listed alongide their botanical descriptions and examples of the plants that fall into the same botanical family.

The public's curiosity about less familiar animals and their role as pets and companions is also reflected in textiles. Wild animals from distant countries could be seen at the Jardin du Roi (now the Jardin des Plantes) in Paris and at the Menagerie at the Tower of London. Some wealthy individuals such as Margaret, Duchess of Portland (1715 – 85) created their own menageries and aviaries where they could enjoy but also study the animals in a controlled, man-made environment. Monkeys were popular pets.

Fashionable clothes have also reflected a more active engagement with nature and the pastimes associated with it. From the late 18th century doctors encouraged the public to visit the seaside for health and recreation. In the following century the advancement of the rail network in Britain made seaside holidays and day trips to the coast affordable to many more people. Identifying and collecting shells, fossils and seaweed became popular hobbies, combining learning with pleasure. These new-found outdoor pursuits started to influence pattern design – a dress in our collection depicts an intricate study of seaweed and other marine organisms.

Collecting ferns to create indoor and outdoor gardens was also a common pastime. Sadly, although fern collecting found approval as a healthy, educational and useful recreation, it led to the widespread damage of fern habitats. Collecting the fronds to dry and press, an activity enjoyed by the novelist Charlotte Bronte on her honeymoon, was a more sustainable alternative to uprooting the whole plant. The fashion for visiting botanical gardens and flower shows and growing tender imported plants is reflected in the textiles from this period. It is far less common to find 19th-century fashions that draw on field and hedgerow flowers. A skirt from our collection features a striking pattern woven in silk which treats each bloom as an individual specimen. The flowers are arranged against the black background fabric as if they had just been taken from a cutting garden, where plants were grown for use indoors.

Animal prints were popular throughout the 20th century. Their 18th century predecessors were more likely to be woven. During the early 1760s silks patterned with simulated bands of ermine and other furs were woven in Lyon in France. Real ermine was used at this time for edging garments and for stoles (a long scarf or shawl worn loosely over the shoulders). It was an expensive fur imported into Western Europe from North America or Russia. Ermine, which is the name given to the stoat in its white winter coat, was distinguished by the dark tip to its tail which was often used to create a black spot on the white pelts.

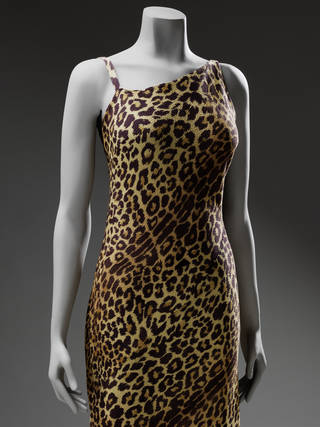

In the 20th century animal prints of all kinds were used in fashion, particularly leopard prints which are distinguished by their appealing pattern of rosettes. These prints were not substitutes for fur but appealed in their own right as eye-catching patterns. In nature pattern often has a different purpose, acting as camouflage to enable concealment.

From the second half of the 20th century to the present day, designers' responses to nature have often been more personal – whether that reflected the simple pleasure of a windy walk or, as in the case of Alexander McQueen, concerns about the harmful impact of human activity on the earth. His last fully realised collection, Plato's Atlantis, imagined a world of climate change, of melting ice caps, submerged land, with human survival dependent on their ability to evolve into amphibious creatures.