Examples of beads with similar, if not identical, forms and designs have been found in archaeological sites around the Atlantic Ocean, in the Caribbean, North America, West Africa, and Europe. These were truly ‘Atlantic objects’, following crisscrossing maritime trade routes that sprung up between Africa, Europe, and the Americas during the early modern period (loosely 1450 – 1750). While irrevocably intertwined with the brutality and commercial greed of the transatlantic slave trade, beads can also be read as objects of resistance, through which enslaved Africans and African Americans asserted their own identities, culture, and communities, despite efforts to eradicate them.

During the 19th and early 20th century, an English merchant named Moses Lewin Levin operated an import-export glass bead business out of London. Imported from glassmaking centres in Europe, the beads were then exported on British ships for trade in West Africa. Levin consequently donated hundreds of these so called ‘trade beads’ to historical collections, some of which now are housed in the V&A. While these examples predominantly date to the 19th century, glass beads have a much longer history as valued and valuable trade goods.

Histories of glass beads in West Africa

A glass bead dating to about 300 – 800BC excavated at Djenné-Djenno in modern-day Mali offers evidence of ancient West African powdered glass beadmaking. Excavations at Ile-Ife and Igbo-Ukwu, two sites in modern-day Nigeria, have revealed medieval European and Islamic beads dating to the 8th century. In turn, Ile-Ife was also a centre for bead production, reusing imported European and Islamic glass as raw material for beads that were then exported north to locations in modern-day Mali and Mauritania.

Accounts written by early modern European travellers record the prevalence and social significance of beads in coastal states around the Gulf of Guinea. Pieter de Marees, a Dutch merchant who travelled to the coast of what is now Ghana in 1600 – 02, wrote that men there tied a “string of polished Venetian Beads mixed with golden beads and other gold ornaments” above their calves and described one ruler as wearing “gold bangles and other beautifully coloured Beads around his arms and legs, as well as around his neck.” One 17th-century Dutch manuscript notes that in the Kingdom of Benin (in modern-day Nigeria), beads were a visual symbol of social status, and the Oba (king) distributed particularly valuable beads as a sign of favour and prestige. Similarly, an illustration in Olfert Dapper’s 1668 book, Description of Africa, of King Garcia II of Kongo receiving Dutch ambassadors in 1642 shows the King of Kongo and his courtiers wearing long strings of what might be white beads around their necks.

Among the objects in the V&A collection is a necklace composed of striped glass beads, with a single pendant made of animal hide, iron, and plant fibre. It was made in the Asante Empire, a wealthy Akan state established in the late 17th century, spreading across much of what is now southern Ghana, the eastern Côte d’Ivoire, and areas in western Togo. The necklace might have functioned as a signifier of status in the Asante court, or perhaps held spiritual significance as 'asuman' – objects charged with protective powers in Akan belief systems. The necklace may have been part of a large quantity of court regalia – including several sacred gold objects – stolen by British troops when they invaded the capital of Kumasi in 1874 during the third Anglo-Ashanti war.

The establishment of a direct overseas route between Europe and West Africa in the 15th century meant that glass beads and other trade goods could be imported from Europe in larger quantities. In 1653, Dutch merchants at Elmina, a trading centre on the coast of modern-day Ghana, requested 19,900 pounds of Venetian goods to be used for trade, including a variety of beads in different colours and designs.

Styles and techniques

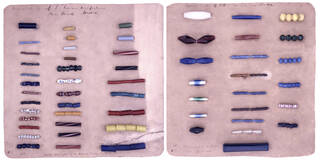

Though many of the glass beads donated by Moses Lewin Levin in the V&A collection date to the 19th century, they give an indication of the diversity of beads which would have been made for export to West Africa in earlier periods, and exhibit centuries-old manufacturing techniques. Drawn glass beads are made by stretching out a tube of molten glass and cutting it into segments to create individual beads, the edges of which can then be ground smooth, or fire polished in the furnace. Wound beads are produced by winding strands of molten glass around a metal prong, which can then be decorated with thin trailings and dots of glass. Millefiori (translating to ‘a thousand flowers’) beads are made by applying small slices from multi-layered glass canes to the surface of the bead, thus exposing the cross sections of the canes to create a vibrant, irregular, mosaic pattern. Another early style of beads traded with West Africa were chevron beads, named and known for their striped, zigzag pattern, commonly in white, blue, and red. First made in Venice in the 16th century, chevron beads are also drawn beads, though the gather of glass is first inserted into a mould to achieve the star shaped design.

Slavery and resistance

From the 14th century, Venice was Europe’s principal centre for luxury glass production. However, glass beads were also produced in Bohemia (now the Czech Republic), the Netherlands, and Britain. The remains of two 17th-century glass furnaces with beads and waste from bead manufacture were found in excavations at Hammersmith Embankment in London in 2001 and 2002. This location was formerly the site of Brandenburgh House, the estate of Sir Nicholas Crisp. Crisp was an English merchant involved in the Guinea Company, a private enterprise which traded for ivory, hides, redwood (used as red dye), and slaves in West Africa. In 1635, he was granted a patent for 'making and vending of Glass beads'. The Hammersmith site offers the first clear evidence of post-medieval glass bead production in Britain.

This increasing production of glass beads, both in Britain and elsewhere, reflects a demand for goods used as barter in the transatlantic slave trade. During the 17th and 18th centuries, vast sugar plantations dotted across the Caribbean and South America became sources of unprecedented profit for European economies. This profit was conditional on the labour of millions of enslaved Africans, transported across the Atlantic Ocean to work under brutal and inhumane conditions. In part, slavery in the Atlantic World was a system of psychological manipulation, whereby the cultural and individual identities of enslaved Africans were intentionally suppressed and eliminated to prevent solidarity and rebellion on plantations. However, glass beads found in archaeological sites in the Americas suggests the persistence (and resistance) of a shared West African heritage that attached ornamental, social, and spiritual value to them. Newton burial ground on the former British colony of Barbados contains the remains of about 570 individuals who were enslaved on the adjacent Newton plantation, established in the 1660s. Several individuals were buried with beads manufactured in Europe. One burial included an elaborate necklace comprised of canine teeth, fish vertebrae, European glass beads, and a bead made of carnelian – a semi-precious russet red stone. It is thought to have belonged to a spiritual healer or leader who practiced ‘Obeah’, a Caribbean belief system with roots in West African traditions. Glass beads were also found in the African Burial Ground in New York, including a strand of about 100 beads around the waist of one interred woman, a form of transhistorical adornment still common in West African cultures today.

Written sources also record the wearing of beads by enslaved Africans. In 1750, the Welsh author Griffith Hughes wrote that enslaved people in Barbados wore beads “in great Numbers twined round their Arms, Necks, and Legs". In 1816, the English author and plantation owner Matthew G Lewis observed that on special occasions, the enslaved women in Jamaica were 'decked out with a profusion of beads and corals.' Given the extremely cruel conditions of the 'Middle Passage' – the voyage across the Atlantic Ocean – scholars have deemed it unlikely that individuals were often able to carry beads with them from Africa to plantations in the Americas. However, slave ship captains occasionally gave enslaved women glass beads, likely in an anxious attempt to prevent revolt onboard, while enslaved individuals also could have purchased and traded beads via informal barter markets on plantations.

Other forms of material culture suggest that glass beads were an established visual attribute in Europeans’ collective conceptualisation of Africa at the height of the transatlantic slave trade. A late 18th-century earthenware beer jug in the V&A collection, made in Staffordshire, depicts a scene of the four continents – all personified as women – supplicating themselves before the figure of Britannia. The kneeling, allegorised figure of ‘Africa’ offers forward a string of beads. These stereotyped and derogatory representations of Africa as a conceptual and geographical entity often include beads.

Trade in the 19th century

After over two centuries of participation, Britain finally abolished the transatlantic slave trade in its Empire in 1807. Consequently, Britain turned to other 'legitimate' trading interests in West Africa. Palm oil, used for soap and candle manufacture, became a desirable source of profit, and imports of the oil from West Africa into Britain soared from 223 tons in 1800 to 31,457 tons in 1853. It is during this period that Moses Lewin Levin operated his import-export business in glass beads. In 1848, he was described as having 'a large supply of beads and cutlery in bond for the Indian and African trade'.

Levin’s business operated until 1913, by which time the nature of the economic relationship between Europe and West Africa had changed. Europe’s concerted colonisation of West Africa occurred throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, during a relatively recent period of militaristic and ruthless imperialism now known as the ‘Scramble for Africa'. Prior to this, the relationship between Europe and West Africa had been one based primarily in trade. Glass beads chart a history of the economic, cultural, and political interaction between these regions throughout a period of over four centuries, a period which also saw the emergence of regular transoceanic trade around the Atlantic and the birth of new transatlantic cultures and diaspora.

Explore related articles and films in our Global Africa collection