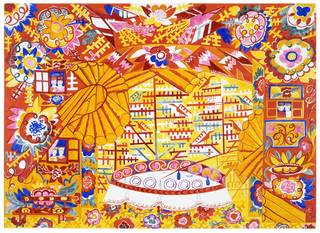

An opera designer works collaboratively with directors. Designers are often responsible for both set and costume design, allowing one seamless vision linking performance to setting. A striking example of this can be seen in the avant-garde backcloth and costume designs by Natalia Goncharova (1881 – 1962) for Diaghilev's 1914 production of the opera-ballet Le Coq d'Or, which are united by their bold colour and simplified shapes, derived from Russian folklore.

In Britain, George Sheringham (1884 – 1937), a decorative painter, theatrical designer and book illustrator, created a very different style of stage set for the light opera, Midsummer Madness by Clifford Bax. The backcloth design, featuring an elegant garden setting, is a typical example of Sheringham's work of the 1920s, drawing on Baroque influences. In 1925, Sheringham won a Grand Prix at the Paris Salon for his mural and theatrical design.

A much starker approach to opera design is seen in acclaimed artist Derek Jarman's marbled paper and cardboard model for Mozart's Don Giovanni. Best known as the director of innovative and controversial films, Derek Jarman (1942 – 1994) trained as a painter at the Slade School of Art, developing a non-figurative, linear style. In 1968 he was commissioned to create sets and costumes for a new production of Don Giovanni by Sadler's Wells Opera. Jarman's concept involved severe geometric spaces, with large pyramids, cones and blocks, which could be moved to suggest the opera's different locations. Interviewed by the Sunday Times (18 August 1968), Jarman spoke of his dislike of "unnecessary detail, which blurs the outlines of sets and costumes".

Another bold, innovative example is the set design for John Taverner's opera, Thérèse, by Alan Barlow (1927 – 2005). Barlow began designing for amateur dramatics in his home town of Coventry. He then progressed to working with director Hugh Hunt at Bristol. When Hunt became director of the Old Vic, Barlow joined him there as a designer. Following a gap in his theatrical career, Barlow returned in 1979 to design the extraordinary set for Thérèse at the Royal Opera House. The opera was intended to flow without scene-change breaks, so the set was required to transform silently, in full view of the audience, from a dying nun's cell, to a children's playground, to the gas chambers of Auschwitz. Barlow achieved this by creating a semi-abstract skull shape in fibre-glass which could be opened up like a giant fan.

Some opera designers look to the past for inspiration. Photographs of John Bury's set for Peter Hall's Glyndebourne production of Francesco Cavalli's La Calisto show a purposeful nod towards Baroque opera staging. First produced in 1651, La Calisto has a typical plot of the period, where gods fall in love with humans and come to earth in disguise, resulting in confusion and identity crises. Seventeenth-century opera was visually extravagant, with elaborate and sophisticated stage effects. Peter Hall, who directed the production, and his designer, John Bury, wanted to recreate the look and feel of the Baroque stage for 1970s audiences. They created old-style stage machines, which used manpower, ropes and counterweights, to enchanting effect.