By the end of the 1870s William Morris, the man who had introduced a radical new naturalism into Victorian pattern design, was a household name. The popularity of his work, much of which used motifs taken from British wildlife, helped develop a new public enthusiasm for 'native design' (previously Paris had been the unrivalled centre of decorative taste). Morris's designs also helped fuel a huge expansion in the market for patterned interior elements of all kinds.

Fashionable, affluent consumers visited specialist dealers and new 'all under one roof' stores to source the materials for complete schemes in the Arts and Crafts style. These progressive interiors combined plain, often rustic-style furniture with highly decorative curtains, fabric covers, hangings, wallpapers and rugs. As Morris increasingly focused more on writing, activism and refining production than on creating his own designs, a new generation of designers began to build on his legacy and to consolidate the expression of pattern in an Arts and Crafts style.

Lindsay Phillip Butterfield (1869 – 1948)

At the turn of the 20th century Lindsay Phillip Butterfield was one of Britain's most successful freelance pattern designers. Trained at the South Kensington National Art Training School in London, Butterfield sold his work to most of the country's leading wallpaper and textile companies. A keen gardener, he focused on producing naturalistic patterns of ordinary British flowers, making his work look stylistically similar to that of William Morris. Butterfield himself said he was inspired by the work of his near-contemporary Charles Voysey, which is characterised by more open, curving forms. A founder member of the Society of Designers (established in 1896), Butterfield taught at art schools including London's Central School of Arts and Crafts, and in 1922 published a book titled Floral Forms in Historic Design.

Walter Crane (1845 – 1915)

Generally considered the most influential children's book illustrator of his generation, Walter Crane also created many memorable designs for wallpaper. Apprenticed as a wood-engraver, Crane had ample opportunity for closely studying the work of contemporary artists such as painters Dante Gabriel Rossetti and illustrator Sir John Tenniel, and his own drawings demonstrate a fine eye for stylised natural detail. Heavily influenced by William Morris, Crane was a committed Socialist and believed passionately in the transformative power of bringing people from every social class into everyday contact with art. It was partly this idea that drove his enthusiasm for wallpaper, although as with much Arts and Crafts work, the barrier of cost probably meant few, if any, of his designs reached working-class homes.

Lewis Foreman Day (1845 – 1910)

Trained as a stained-glass maker, Lewis Foreman Day was one of the most commercially successful designers of his generation. Starting his own business in 1870, he went on to produce a range of domestic designs, including textiles and wallpapers. In 1881, Day became the Artistic Director of a leading textile-printing firm in Lancashire, Turnbull & Stockdale, a role that allowed him to broaden the popularity of his designs. A founder member of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society (established in 1887), Day also lectured and wrote books on design. Although his style has sometimes been judged as derivative, he was an excellent draughtsman and sold his memorable, rhythmic designs to a range of fashionable firms and retailers.

John Henry Dearle (1860 – 1932)

John Henry Dearle began his career in 1878 as an assistant in the showroom of William Morris's interiors firm, Morris & Co., where his talent for drawing soon earned him a place as a tapestry apprentice to Morris himself. By 1890 Dearle had become Morris & Co.'s chief textile designer, and became Art Director of the entire firm after Morris's death in 1896. Dearle's status as a designer suffered from his close association with Morris, with his work often wrongly attributed to his famous boss. Although Dearle's early textiles were closely based on Morris's style, his mature work, which was influenced by Persian and Turkish patterns, shows greater originality, and his naturalistic flower designs were very popular at the beginning of the 20th century.

Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo (1851 – 1942)

Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo was an architect, designer and founding member of the Century Guild of Artists, a group founded in 1882 to support artists working in domestic design. Mackmurdo designed most of the repeating block-printed textiles that were produced on behalf of the Guild. As a young man he was strongly influenced by the drawings of the painter Edward Burne-Jones and his swirling designs for stained glass. Mackmurdo often based his patterns on real but strange-looking natural forms, such as, in one pattern designed in around 1882, the crinoid or 'sea lily', a primitive animal related to corals. Dynamic and flamboyant, Mackmurdo's patterns prefigure many of the elements of Art Nouveau.

Sidney Mawson (1876 – 1937)

A landscape painter and teacher of textile design at the Slade School of Art, Sidney Mawson was one of the most commercially successful pattern designers of his day, working as an unacknowledged freelance artist for most of the leading English textile and wallpaper companies. Mawson was a flexible designer whose finely drawn naturalistic patterns in clear bright colours were created with an eye firmly on popular tastes. Many of his designs were sold through London store Liberty, which helped make Arts and Crafts style accessible to a wider public. Mawson was a pragmatic naturalist: without the forensic interest in nature of a designer like William Morris, he was able to adapt the size and shape of his forms to better suit his designs.

Allan Francis Vigers (1858 – 1921)

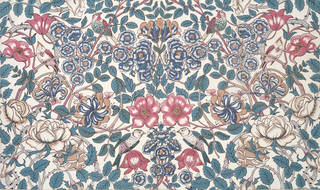

Trained as an architect, Allan Francis Vigers completed his training with Charles Barry, the designer of the new Palace of Westminster and, most famously, its clock tower, 'Big Ben'. Although he later set up his own architectural practice, Vigers chose instead to focus on smaller-scale work, becoming an acclaimed designer of furniture, wallpapers and textiles. His pattern work directly echoes that of William Morris, in that it is filled with the unpretentious blooms characteristic of an English garden: columbines, roses, pansies, cornflowers, lavender, etc. But, as with Morris, Vigers' naturalism was not quite what it seemed, with his intricate flowers arranged in highly stylised formations, often on muted and rather moody backgrounds.

Charles Voysey (1857 – 1941)

Charles Voysey was one of the Arts and Craft movement's most successful architects, as well as producing some of its most striking designs for furniture and other interior elements, including wallpaper and textiles. Elegant and quietly expressive, Voysey's work demonstrated the designer's strong belief in 'less is more'; his drawings for flat-surface design demonstrate the same restraint and interest in clear space that is evident in his furniture and other objects. Although Voysey wouldn't have accepted it himself – as a British practitioner of Arts and Crafts design he would have had little enthusiasm for such an exuberant, 'European' style – it is generally agreed that his dramatic large-scale florals laid the foundations for the development of Art Nouveau, particularly the work of Czech painter and decorative artist Alphonse Mucha.

Discover more about Arts & Crafts.