Photos remember forgotten generations.

During photography’s budding infancy, America was undergoing a rough adolescence. Only 20 years after the introduction of the daguerreotype – the first publicly available photographic process – the nation was facing civil war. The American Civil War (1861 – 65) became one of the first photographically documented mass conflicts. Easily circulated, direct and unflinchingly literal, the photograph established new ways of understanding what it meant to be at war, particularly with one's fellow citizens, all on native soil. For the first time Americans saw violence on a national level, relatively close to real time.

Since the conception of the American nation, the South has defied categorisation. It is known for its idiosyncratic characteristics. It is a place of high industrialisation and agriculture, systemic oppression and indignant liberation. The Southern States continue to act as a hothouse for American politics, bearing witness to a nation in the making. The camera has become the eye of this witness.

The V&A began collecting photography as early as the 1850’s and now holds one of the largest public collections of American photography outside of North America. It is in this diverse photographic chronicle that we can trace an understanding of how the concept of the American South was invented. Photography's unique power, its capacity to record something close to a representative reality, provides a route into a past otherwise closed. We can see how people lived, dressed, worked and loved. We can see how the nation of America was formulated, evolved, adapted and grew. And we can see how the South continues to build an identity as complex as any other region. There are as many understandings of the American South as there are images of it. Here, we trace some photographic answers to the question of Southern identity in America.

Labour, class, economies

The American President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882 – 1945) once described the South as "America's number one economic problem". He was speaking at a time of major economic turmoil and social disenfranchisement. By 1910, there were 2 million children in the labour force, leading photographers like Lewis Hine, with support from the National Child Labour Committee, to document them in hope of bringing about major social and governmental reform.

Hine’s photographic style – documentary with a strong socio-political focus – can be said to be a precursor to a style infamous to Southern photography throughout the early to mid-20th century. With its ability to represent reality, the camera has become one of the dominant devices of social change. During the Great Depression (1929 – 39) and subsequent reforms of the New Deal, public and state interest in an impoverished and racially divided South caught the attention of the nation and beyond. With many operating through grants, bursaries, commissions and assignments, American photographers flocked to the rural South in search of a social documentary.

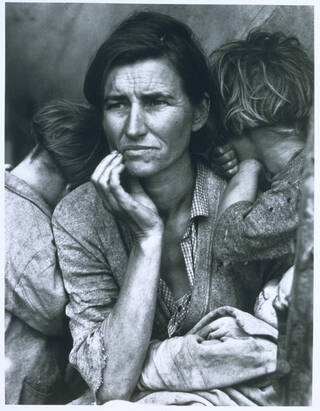

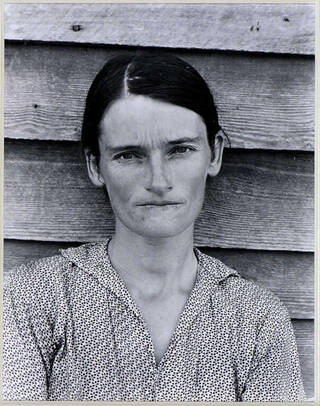

Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Gordon Parks each received funding from the Farm Security Agency (FSA), Roosevelt’s New Deal agency concerned with the future of American agriculture. Operating from 1937 to 1946, the FSA collected visual data on the ongoing farming crisis, in turn harnessing such images to argue for major reform. Lange, Evans, and Parks produced some of their most iconic images during their trips and, in the process, helped build an enduring visual understanding of Southern life. Parks returned to the South for Life magazine, becoming one of the few northern Black photographers to risk his life and venture down south. Photographers, such as Robert Frank, used Guggenheim scholarships to make similar pilgrimages, resulting in the now seminal 1958 photobook The Americans.

At a time of enforced racial segregation and discrimination against African Americans, many of these photographers used their whiteness to gain photographic access to deeply racialised sites – their white skin making people more at ease when the camera came out. In doing so, they were able to document a racially-motivated and oppressive labour system, one keeping millions – on both sides of the colour line – hungry and poor. From the farmer to the factory worker, the nanny to the plantation picker, one of our only access points into the worlds of these workers remains the photographic.

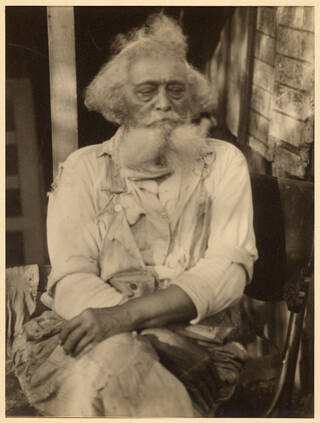

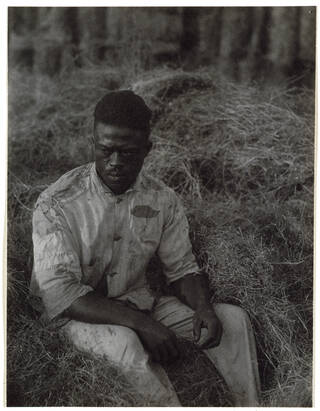

Doris Ulmann, a contemporary of Lewis Hine, shifted her practice and geographic focus to portray these working classes. Often documenting African Americans, she developed a practice centred on portraits of respect, understanding, and character. Many of her portraits, such as Richard Talbert, Farmer, 76 Years of Age, Fayette Country, Kentucky and Man in a Hayfield, are tenderly crafted records of men at work. Tired faces and stained clothes, rural backdrops and averted gazes do nothing to take away from the care, attention, and dignity of her photography.

Later in the century, Barbara Norfleet also uses documentary to build a sympathetic and political understanding of Southern life. At first glance, Private House, Summer, Mississippi (1984), is a candid picture of the wealthy, but a closer look reveals the haunting reflection of a Black domestic servant. Norfleet uses the mirror to play with scale and perspective – the foreground becomes the background, the photographer invisible. It leaves an impression of entrapment – an anonymous Black figure stuck in the image, mirror and house. This is juxtaposed with the effortlessness of the woman as she gets ready to go out. In this image, Norfleet reaffirms the history of the American South in arresting, brutal honesty. Class and racial divides have built and furnished this lavish home, resulting in a space in which the two subjects remain unequal. It suggests that once the scene is over, the woman will walk away and out to her party whilst the Black figure will remain.

Throughout the Great Depression, Americans consumed images of Southern pain, poverty, and perseverance. This explosion in Southern documentary photography begs the question: with most images produced by non-southerners, who from the South gets to tell their story? This contested narrative becomes a key element we can trace through Southern American photography. Many of the now-iconic farm workers photographed by Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans had issue with becoming a symbol of Southern poverty. Who has the right to document a land, a people, a history? Who is southern enough, white enough, local enough? The V&A’s holdings cover a range of answers to this unending question.

The car and the road

The first photographic institutions in the American South were studios – static spaces where people came to the camera. Technological advancements from the late 19th century and into the 20th created lighter, more mobile cameras, in turn bringing the camera to the people. Before the rationing of rubber and oil during the Second World War, automotive transport was a key means for photographers to get around, many traveling across states and ending up in the South.

The United States is the land of the automobile, a place literally built for the car. The South interconnects through a web of highways and state lines, roads built upon roads. Subsequently, the road, the car and the built environment became key characters in much Southern photography.

In her 2017 series Dark Waters, Kristine Potter examines mythologies unique to her southern Texas homeland. The series draws on the sinister imagination of 19th and 20th century ‘murder ballads’, songs which chart the tragedies of local murdered women. Part folklore, part oral history, Potter reflects on these grisly tales through her photographs, often centring female subjects within a recreated narrative. In Impasse at Sodom's Creek (2017), a snake, possibly roadkill, interrupts a provincial scene and yet fits into Southern life without shock – danger may be afoot, but nothing is out of the ordinary.

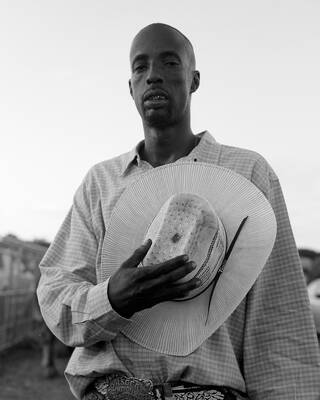

In a similar fashion, Rahim Fortune employs mythology and folklore in search of truth to his Texas home. The series Hardtack, pushes against traditional notions of Americana, painting poignant and technically precise portraits of African Americans and the land they call home. In Powerlines, Taylor, Texas (2023), the artist is on the move, travelling between Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi. Even in this work, devoid of any Black subjects, the image becomes a reflection on Black life in the South. When seen alongside the rest of the series, featuring praise dancers, rodeo queens, and modern Black cowboys, Fortune builds a world not grounded on oppression and violence, but one of resilience and tenacity.

Teresa Margolles, a Mexican artist working along and around the Mexico/US border, also uses the road to explore themes of violence, memory, and mourning. In her 2010 video Irrigación, the artist films a truck as it pours 5,000 gallons of water onto Highway 90, running through Presidio County, Texas, 250 miles from the Mexican border. Irrigación is a response to the murder of more than 500 men, women and children in the first three months of 2010, in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico by drug cartels. Margolles placed wet cloth directly onto the sites of violence to absorb any physical remnants of the crimes, before soaking them in water. This same water was then poured out onto US soil, implicating the nation in a violent cycle that they can never wash away.

Shot 32 years later and 518 miles away, in An-My Lê’s Fragment IV General Robert E. Lee Monument, New Orleans, Louisiana, the road becomes part of a wider chorus in a meticulously shot, detail-heavy urban environment. The whole scene, but particularly the statue of confederate general Robert E. Lee – since removed – builds a matter of fact report of the layered constructions (or fragments) of the histories we live within. Like Margolles, Lê positions the built American environment as a witness to contested histories and violent pasts. Her work sits alongside other artists, such as Peggy Buth, Ed Ruscha, and Stephen Shore, who documented the socio-political landscape of America through literal depictions of the road.

Race, civil rights and Doris Derby

Segregation – the state-enforced separation of American citizens by skin colour – was presented at the time as a utopia. The racist concept argued that America would reach new heights if it became ‘separate but equal'. This enforcement through the Jim Crow laws continued a racialised history that embodies the American South for many. The Southern States are a region heavy with a painful and troubling history of racism – one that evolved into new forms after the Civil War and Abolition of Slavery. Despite changes in law, some legacies are hard to shake.

Yet, despite millions of photographs documenting America, this alleged utopia never appears. The apparent benefits of segregation cannot be found in a single photograph. What we do have photographic evidence for though, is the reality of its impact on American life. The 19th century saw the invention of new photographic processes and technologies. At the same time as abolitionist movements laid the groundwork for the eventual emancipation of enslaved African Americans. These histories orbit each other – as anti-slavery rhetoric grew, so did the influence of the photograph. Despite there being photographic documentation of the final decades of the slave trade, much of this crime against humanity remains unphotographed and unseen. Yet, from the Civil War to modern day, American racial injustices find themselves in front of the camera, again and again.

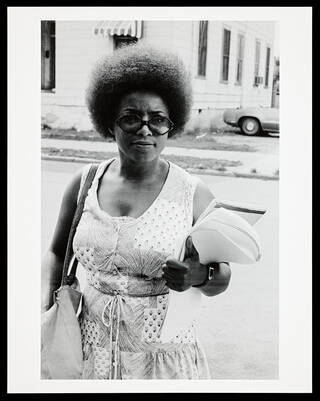

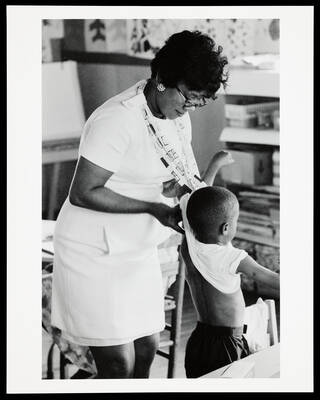

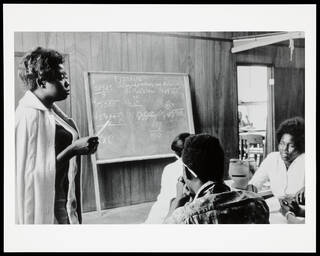

Doris Derby provided an alternative view on this fight for civil rights. Where photographers such as Danny Lyon and Builder Levy focused on the front lines of protest, Derby instead turned her attention to the intimate side of the everyday struggle found across the American South – the slower, quieter, yet equally essential sites of women, families, back roads, meeting spots, and domestic interiors. Despite her quieter subjects, her practice was no less dangerous, as unlike white activist photographers, she wasn't able to blend in on either side of the protest, to freely travel by bus or car. Derby was a Black woman documenting Black women. Her decision to document the operational everyday of the Civil Rights Movement leaves us with a fuller and richer understanding of a key moment in human history.

What all these photographers had in common was a desire to understand the American South – its people, its places, its histories, and possible futures. Their insights were as varied as the faces and places they photographed and remind us of the difficulties of trying to portray the American South as a succinct and easily understandable entity. Instead, we have what An-My Lê calls 'fragments', built over centuries of violence and faith, pain and love. We can view photographs of the South as materials to be built on top of each other, and with each new camera, photographer and eye, the image of the American South becomes a little more complex, and essential to a wider reading of what makes America, America.