Throughout the history of photography the camera has often made an appearance in its own image, from the glint of Eugène Atget’s camera in a Parisian shop window from the 1900s, to the camera that serves as an eye in Calum Colvin’s 1980s photograph of a painted assemblage of objects.

Many images of cameras exploit the instrument’s anthropomorphic qualities. Held up to the face, as in Richard Sadler's portrait of Weegee, it becomes a mask, the lens a mechanical eye. It conceals the photographer’s features yet reinforces his or her identity. Set on a tripod, it can take on human form, appearing like a body supported by legs, and can stand in for the photographer.

Photographs that include cameras often draw attention to the inherent voyeurism of the medium by turning the instrument towards the viewer. Such images confront the viewer’s gaze, returning it with the cool, mechanical look of the lens. The viewer cannot help but be aware not only of seeing, but of being seen.

'Venetian mirror circa 1700', by Charles Thurston Thompson

As early as 1853, Charles Thurston Thompson (1816–68), the first official photographer to the South Kensington Museum (as the V&A was then called), recorded his reflection, along with that of his camera, in the glass of an ornate Venetian mirror. Loan objects such as the mirror were photographed so that photographic copies could be sold to designers, craftsmen and students, and also filed in the Museum's library for study. By recording not only the frame’s intricate carvings but also his reflection and that of his boxform camera and tripod, Thompson showed the very process by which he made the image. It gives us a vivid glimpse of a photographer at work outdoors in the early days of the Museum.

.jpg)

'Shopfront, Quai Bourbon, Paris, France', by Eugène Atget

The reflection of Eugène Atget's (1857–1927) camera is an appealing detail in this photographic record of Parisian architecture from the turn of the century. Atget's photographs had a primarily documentary role - this image was purchased by the V&A in 1903 as an illustration of Parisian ironwork. Yet it carries a strangeness which has fascinated 20th-century photographers. His photographs acquired artistic status in the mid-1920s when they were 'discovered' by artists associated with Surrealism.

'Bill Brandt with his Kodak Wideangle Camera' by Laelia Goehr

Laelia Goehr (1908–2020), learned photography from Bill Brandt, who poses for this portrait with his newly-acquired Wide-Angle Kodak. This model was originally used by police to photograph crime scenes - the lens provides 110 degrees angle of view, equating approximately to a 14/15mm lens on a 35mm camera. Brandt experimented with it to produce his series Perspectives on Nudes, the same year as this portrait was taken. Brandt's camera, which was made of mahogany and brass with removable bellows, was sold by Christie’s in 1997 for £3450.

.jpg)

'Mediterranean Fortnight', by Elsbeth Juda

Elsbeth Juda (1911–2014) was a British fashion photographer who worked for more than 20 years as photographer and editor on The Ambassador magazine. This image was shot at an archaeological site in Cyprus for a story on British fashion abroad. The model appears to pose for a local tintype photographer with a homemade looking camera. Tintype, also called ferrotype, was an early photographic process which produced an underexposed negative using a thin metal plate. Tintype photography was around 100 years old when Juda took this shot.

'Camera on black cloth'

The camera pictured here is a Super Ikonta C 521/2 camera, produced by the German company Zeiss Ikon from about 1936 to 1960. It has been carefully lit and arranged on a velvet cloth as if it were a still-life subject, by an unknown photographer.

'Weegee the Famous', by Richard Sadler

Coventry-based portrait photographer Richard Sadler (b. 1927) photographed the self-proclaimed 'Weegee the Famous' in 1963. Weegee was a New York press photographer who gained his nickname - a phonetic spelling of Ouija, the fortune-telling board game - for his reputation for arriving at crime scenes before the police. His fame was international by the time this portrait was taken. Weegee's visit to Coventry coincided with ‘Russian Camera Week’ at the city's Owen Owen department store. The camera Weegee holds up to his eye here is the Zenit 3M, a newly-introduced Russian model made by the Krasnogorsk Mechanic Factory between 1962 and 1970.

A few years later Weegee made a comparable self-portrait in which the camera (this time a recent Nikon model) obscures his right eye.

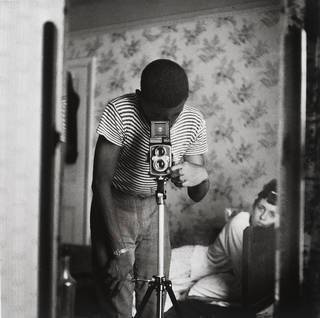

'Self-portrait in Mirror', by Armet Francis

Armet Francis was born in Jamaica in 1945 and moved to London at the age of ten. His photographic career began in his mid-teens when he worked as an assistant for a West End photographic studio. His early photographs show him experimenting with the camera as a technical device and a tool for self-representation. The camera in this self-portrait is a Yashica-Mat LM twin lens reflex, an all-mechanical model introduced in 1958, with an inbuilt light meter. It records his identity as a professional photographer, while the surrounding scene offers an intimate glimpse into his personal life.

'Season's Greetings', by Philippe Halsman

American portrait photographer Philippe Halsman (1906–79) and his wife Yvonne made annual playful Christmas cards. For their 1967 card they posed on ladders, pointing cameras at each other. The cameras - 4 x 5 inch twin lens reflex models - were designed by Halsman himself and made locally. This format was much larger than was normally available (2¼ x 2¼ inch was standard), giving better quality negatives, and the reflex viewing was particularly suited to capturing motion - a central feature of Halsman's photographic style. Darkroom manipulation was used to exaggerate the height of the ladders and tripods.

'Untitled', by Calum Colvin

Calum Colvin's (born 1961) work combines the three-dimensionality of sculpture with the fixed perspective of the camera. He creates elaborate installations, painting directly onto an arrangement of disparate objects and then photographing them. The result is a complex image that seems to emerge from chaos and surprise the viewer. In this example Colvin creates a visual pun with a camera that stands in for an eye.

'Lily Cole and Giant Camera', by Tim Walker

British fashion photographer Tim Walker (born 1970) has collaborated with the art director and set designer Simon Costin for over a decade, and Costin’s oversized props feature in many of Walker’s sparkling, magical scenes. Costin based the giant camera on Walker’s 35mm Pentax K1000. Walker apparently found inspiration for this shoot in a 1924 Vogue illustration.

Find out more about the V&A's photograph collection.