Sir William Davenant

The first English opera is generally regarded as Sir William Davenant's The Siege of Rhodes, performed in 1656 at Davenant's home, Rutland House. At this time, theatres were closed and plays were forbidden by law. Music, however, was still permissible. It is possible that Davenant included the music element as a way of getting round the law, rather than an attempt to write a true opera. A second part of The Siege of Rhodes was performed after Charles II was restored to the throne. A passionate Royalist, Davenant, and fellow dramatist Thomas Killigrew, were then granted royal patents, which gave them a virtual monopoly over presenting drama in London.

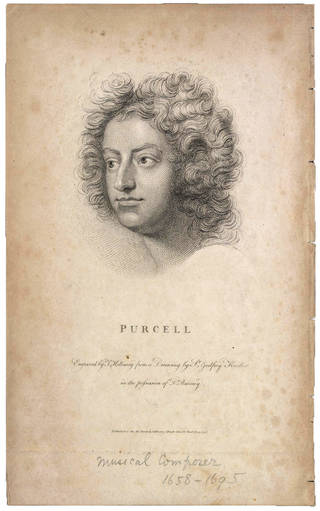

Purcell and English semi-opera

For decades, Italian and French opera failed to make an impact in England, so composer, Henry Purcell (1659 – 1695), devised the semi-opera, a peculiarly English form, which combined singing with spoken dialogue, elaborate costumes, scenery, effects, dancing and music. This half-sung, half-spoken hybrid flourished in the 1670s and lasted into the 18th century. It horrified the French and Italians, for whom opera was very formal, and one French traveller of the time described it as a 'hotchpotch'. Even so, fully-sung opera in English was not established for another 200 years.

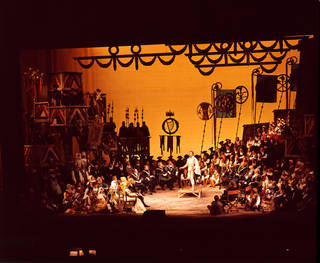

The Fairy Queen, based on Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, was the most lavish of Purcell's semi-operas. Shortly after Purcell's death in 1695, the musical score was lost. It wasn't performed again until 1911, following the rediscovery of the score, when it was staged by the students of Morley College, London, under the guidance of Gustav Holst. As only one copy of the score existed, the students spent a year copying out the 1,500 pages of manuscript. In 1946, when the Royal Opera House re-opened after World War II, The Fairy Queen was the showcase for the newly formed opera company and resident ballet company, the Sadler's Wells Ballet. It was an ambitious, lavish production that seemingly pleased nobody – the opera audience was bored of the dancing, the dance audience was bored of the singing and the drama audience did not come at all.

The Fairy Queen was again staged in 1995 by the English National Opera. Their approach was to make it accessible to as wide a public as possible. Producer David Pountney eliminated the actors and transformed it into a dance-drama centred on Oberon and Titania. Puck wore a bra, a huge tenor appeared in a leopard skin ball gown, other characters wore designer underwear with wellington boots, and Oberon had to sing while working out on the parallel bars.

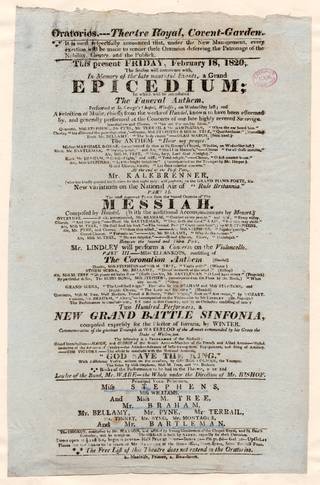

Oratorio

In the late 18th and 19th centuries, oratorio, rather than opera, became the favoured English vocal form. Developed by George Frideric Handel, oratorio set a sacred or biblical story to music. Like opera, it was split into arias (long accompanied songs for a solo voice), choruses and musical interludes, but with more emphasis on the chorus. Oratorios were usually performed in a concert hall with no scenery or costumes. Handel's most famous oratorio was The Messiah, first performed in Dublin in 1741. At the time, English singers were thought to be unsuited to grand opera, so oratorio became their musical release. Many large choirs were formed in the 19th century, giving employment to generations of professional British singers, whose experience became invaluable when permanent English opera companies were eventually set up in the 20th century.

Sir Thomas Beecham

In the early 20th century, Sir Thomas Beecham established the British National Opera Company, but struggled to keep it afloat, despite the assistance of funds from his father (derived from the famous pharmaceutical empire of the same name). Most of the operas in the Beecham Company's repertory were performed in English. Beecham took a lot of trouble over the translations, testing each phrase with his leading singers to see which words they could most easily sing on each note. Publicity postcards were produced featuring the singing stars of Beecham's opera company, such as Frederick Austin and Fanny Moody.

Fanny Moody

Fanny Moody was born in 1866, when most opera was confined to London and for limited seasons. She sang with the Carl Rosa Opera, a touring company, where she met her husband Charles Manners. In 1892 she was the first English Tatiana in Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin. In 1898, she and her husband formed the Moody-Manners Opera Company. They appeared at Covent Garden, but most of their life was spent touring Britain. Moody sang a wide range of roles, including Wagner, although she was most suited to roles like Cio-Cio-San, the heroine of Puccini's Madam Butterfly.

Lillian Baylis

The establishment of a permanent English opera company was aided by the passionate conviction of one woman, Lillian Baylis, at the Old Vic. Baylis brought opera to new audiences who came to hear music, rather than to be seen. Many were clerical and white-collar workers, who had benefited from improved education and were now eager to explore literature, music and theatre. Baylis' work laid the foundation for both the National Theatre and the English National Opera.

Initially, Baylis was committed to staging affordable theatre, putting on popular temperance concerts for working class audiences as an alternative to the pub. She saw no reason why they shouldn't also enjoy Shakespeare, opera and ballet, so in 1912, she applied for a full theatrical license. She had no money to mount grand productions, so the shows were visually unimpressive and the singing was only adequate. In the 1930s, Baylis moved the opera and ballet to the Sadler's Wells theatre. There was now time for adequate rehearsals so standards improved. The repertory was based on well-loved operas by Rossini, Verdi and Wagner, but also introduced Russian composers, such as Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov.

The Royal Opera House

Until the mid-20th century, the Royal Opera House was only used for opera for part of the year. The rest of the time, it presented plays, pantomimes, revues and even ice shows. After serving as a dance hall during the Second World War, it reopened in 1946 as the National Theatre for opera and dance. Sadler's Wells Ballet moved in as the resident ballet company and plans were made to set up a permanent British opera company that could also play host to the great international opera stars.

Over the next ten years, the first generation of British and Commonwealth opera singers emerged – Geraint Evans, Joan Sutherland and Jon Vickers. Alongside them appeared the great international singers like Maria Callas, Tito Gobbi and Luciano Pavarotti. In the 1950s and 1960s the Royal Opera was noted for its high production standards.

Wagner's opera, The Mastersingers of Nuremberg was staged in 1957. It was the full version, sung in English, lasting five and a half hours. The production was directed by the German singer, Erich Witte, but during rehearsals the tenor singing the leading role of Walther had to withdraw and Witte learned and sang the role, in English, at only two weeks' notice. Within 12 years of the opera company starting, it could field an almost completely British cast in one of Wagner's most demanding operas.

Margherita Wallmann was the first woman to direct a full-length opera at Covent Garden, with Verdi's Aida in 1957. She also choreographed the ballets and drilled sixty volunteers from the Welsh and Scots Guards who were appearing as the triumphant Egyptian army to the strains of Verdi's famous march. Permission for guardsmen to be used as extras at Covent Garden was first given by Queen Victoria and continued well into the late 20th century.

English National Opera

In the second half of the 20th century, the Sadler's Wells Opera concentrated on producing opera in English. Their first great success was the world premiere of Peter Grimes, which heralded the arrival of Benjamin Britten. Britten became the first English opera composer of international standing. In 1968, Sadler's Wells Opera moved from its cramped base in Islington to the London Coliseum in the heart of London's West End. In 1974 the company became English National Opera.

In the 1980s, David Pountney and conductor Mark Elder developed a more radical and idiosyncratic production style. Their operas had a cartoonish energy and were very visual. This shocked some of the more conservative members of the opera going public, but appealed to a new and younger audience. Gilbert and Sullivan fans were also surprised by Jonathan Miller's production of The Mikado, which was performed as a 1930s musical comedy with Yum-Yum and her friends dressed in St Trinians-type costumes.

Regional opera

The growth of opera in the late 20th century was not restricted to London, there is now more opera being performed nationally than at any other time in British theatre history. Welsh National Opera began with occasional performances in 1943. Scottish Opera was founded in 1962 and Leeds-based Opera North was founded in 1975 as a northern base for English National Opera. It is now an independent company.

The most famous opera company outside London is Glyndebourne, East Sussex, with its theatre attached to the country house of the Christie family. Glyndebourne is famous for its long intervals during which the audience picnic in the gardens. The first theatre was built in 1934 by John Christie for his opera-singer wife, Audrey Mildmay. In the 1930s conductor Fritz Busch and producer Carl Ebert, gave British audiences the opportunity to experience Mozart's work. It was here in 1934 that Cosi Fan Tutte was first performed in its entirety in England – nearly 150 years after its first performance.