The term Gothic was first coined by Italian writers in the later Renaissance period (late 15th to early 17th century). The word was used in a derogatory way as a synonym of 'barbaric'. They denounced this type of art as unrefined and ugly and attributed it to the Gothic tribes which had destroyed the Roman Empire and its classical culture in the 5th century AD.

Abbot Suger (about 1081 – 1151) is widely credited with popularising Gothic architecture. In 1140 – 44 Suger renovated the eastern end of his church, the abbey of Saint-Denis in Paris, using innovative architectural features, which had evolved or been introduced previously in Romanesque architecture (6th – 11th century). These features enabled Suger to increase the height and the volume of the abbey and to suffuse it with light.

The Abbey of Saint-Denis became the prototype for the construction of a series of great Gothic cathedrals throughout northern France, famously at Notre Dame in Paris, as well as in Soissons, Chartres, Bourges, Reims and Amiens. The new Gothic style emerging in France was rapidly taken up in England, where it was used in two highly important buildings: Canterbury Cathedral and Westminster Abbey, where royal coronations took place.

In order to help support the weight of these taller buildings, Gothic architects constructed rib vaults, where the ceiling surface was divided into webs by a framework of diagonal arched ribs, and flying buttresses, great arches that extended out from the upper portion of external walls that helped to push weight outwards. Although buttresses had been around since the 3rd century, they became more sophisticated under Gothic architects. New arches carried the thrust of the weight entirely outside the walls, where it was met by the counter-thrust of stone columns, with pinnacles placed on top for decoration and additional weight.

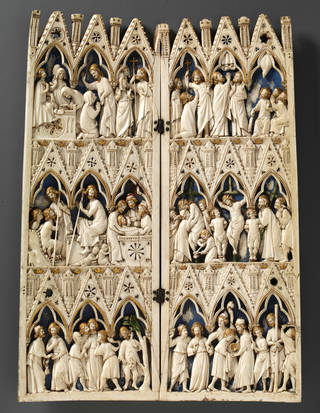

Pointed arches were an important characteristic of Gothic architecture that could give the impression of soaring height and more practically they could support heavier loads than the earlier round arches. Pointed arches were used in arcades, vaults, doors, windows and niches, but also as architectural motifs found on Gothic objects where they served as frames for figures or narrative scenes.

Another key feature of Gothic architecture was the extensive use of stained glass, and a revival of the medieval rose window, which brought light and colour to the interior. Innovations in tracery – the stone framework that supports the glass – also meant windows could be larger and of increasingly complex patterns.

Gothic artists were keen to engage the viewer's emotion more directly than earlier art styles. Where previous figures in sculpture and painting had appeared stiff and stylised in form, Gothic figures appear more realistic, with natural poses and gestures, full of tender feeling and strong emotion. Figures in Gothic art often curve or sway in an 'S' shape, the pose enhanced by the hanging folds of their clothes. These artists understood that viewers were more likely to understand and identify with the stories in a work of art when the figures expressed human emotion. With sacred images this helped to inspire religious devotion.

Artists who worked in the Gothic style also paid close attention to natural forms and were able to reproduce them with remarkable accuracy. Leaf forms were especially popular in England, and churches were often decorated with a variety of recognisable species.

The 13th and 14th centuries in Europe were a period of conspicuous artistic consumption on a lavish scale. Its first patrons were bishops and abbots, but the power and sophistication of the new Gothic forms soon appealed to kings and nobles. The rise of cities, the founding of universities, and the growth in trade in this period also created a bourgeois class who could afford to patronise the arts and commission works. Gothic art was at first associated with French political power, but as the style spread, each country's artists and patrons found ways of adapting the style to their own aims and ideals.