Dr Lisa Skogh: Hello, you are listening to the V&A Podcast series What was Europe? A New Salon. In this series of four conversations, we bring together 30 experts to discuss the geographical and social-historical landscape of Europe from 1600 to 1815, together reflecting on its intercultural exchanges and ephemerality and making connections to the Europe we know today.

Professor Bill Sherman: Hi everybody, I'm Bill Sherman, Head of Research here at the V&A. It's a real pleasure to welcome you to the third in a series of salons called, 'What was Europe?’, marking the opening of the V&A's spectacular new galleries devoted to art, design and culture in Europe from 1600 to 1815. It's actually a salon within a salon, and we're really starting to experience that now in our third of these events.

We're in a room which celebrates and embodies the salon, both with its content and information, but especially in its action, its embodiment. We're sitting with a space which was specifically commissioned from the Cuban art collective, Los Carpinteros, and it's a globe representing the salon environment and the enlightenment that it drove, but it doesn't really become a salon until we do something like this.

And it was a very, very interesting idea, I think, for the museum to not fill its room with objects within a gallery setting that has over 1,100 objects. To have a room with less density of objects and more a space where we can do and explore and create what the space is actually supposed to be interrogating.

So, what this space really is becoming, for us, is a space to ask both what was Europe?, which is the subject of these conversations, the third of which is tonight. And that is an evolving conversation and it's one that becomes timelier by the minute. It's been an incredibly timely time to think about what was Europe? And what is Europe,? And what will be Europe?

But it's also I think what is a museum and what is Europe within a museum, and that has emerged over the last two conversations as an incredibly interesting conversation. So it adds, I think, a lot to be within a museum setting rather than an empty room or a university and it's real... or a home for that matter, which is where we should be, with drink, which we're not allowed to have, sadly, for this particular salon.

But it's a very good setting for us to talk both about what was Europe and what is a museum and what is Europe within a museum, and that's really the topic of these conversations. So, before we begin, we'll have a few more words about the topic of today's conversation from Simon Schaffer, Professor of the History and Philosophy of Science at Cambridge, and Doctor Lisa Skogh, Research Fellow here at the V&A and the recipient of the British Academy's Rising Star Engagement Award that funds this fascinating series. So, Simon, over to you.

Professor Simon Schaffer: Hi, welcome to, as Bill has said, the third of these salons. Many of you have been to previous meetings. In order to mark the beginning of Lent today - it's Ash Wednesday - the V&A has decided to give up Eurocentrism - but only for Lent.

The problem of Europe seen through non-European eyes, of course, is exactly of the same antiquity as the scope of the collections in this amazing museum. That's to say it, in many ways, and many of us I think will want to speak to this during this evening's debate, in many ways it absolutely defines what counts as the collections of museums in general and surely this one in particular with its colonial and imperial and global provenance and ambitions.

In thinking about this evening's topic, I was reminded of a book which, as you can see, I've read extremely religiously over the years, look at the cover, 'The Exotic White Man' which was printed in 1968 and authored by the then ethnography curator, one of the ethnography curators, at the British Museum, Cottie Burland. Who, in other respects, was one of the British Museum's experts, then, on Latin American and more generally American material. Very widely read author on Mexica, on Inca, and on Inuit material. In collaboration with a group of extremely interesting photographers, he put together a collection of images of Europeans made by particularly African, South and East Asian artists and experts.

The work dates, but it's still provocative. It certainly dates. Here's how the preface ends: "The non-European artist is somewhat prone to see us as a comic creature. Our features were odd, our pinkish colour somewhat revolting, our kinder moments endearing, and this is how we were seen; odd creatures from far away who were sometimes quite charming and sometimes hatefully cruel.

In this book, we'll have to take ourselves as others found us." Now, obviously there's much in that tone of voice and content that one now finds completely insupportable and objectionable. But the project of, as it were, rendering symmetrical something like the European gaze, I think is still rich and complex and very high on the agenda of the collection in the middle of which we're sitting.

Two things in particular seem to me to be important, but you're the experts and will correct and ignore me. One is that there seems to be a real challenge to our analytical tools our vocabularies, and no doubt we'll have a lot to say about that in making sense of what these other interlocking gazes, the creative mirrors that are involved in thinking Europe seen through non-European eyes might involve.

Especially so because when Burland was writing, it was self-evident to him that accounts would be being read, as you heard in the passage I've just quoted, by Europeans. The 'we' there is unambiguous, and now surely it must not be and cannot be.

A second, more important, theme, seems to me to be the need simultaneously to register, as I've said, that kind of symmetrical account with an account that never downplays or ignores relations of exploitation, violence and subalternity that emerge in precisely the period covered by these galleries. That's to say from the middle of 1500s [1600] to the early 1800s.

So, it's not that a balancing act is required, then, it's what's required is something I hazard like a politicisation and re-politicisation of the various aesthetics and vocabularies that we're trying to use in our conversation. Think finally of some of the terms that are clearly on the agenda for the theme 'Europe seen through non-European Eyes'.

They're also terms that are absolutely of the essence, both for, for example, the discipline of history of the sciences and for art history, too. I'm thinking of words like icon, idol, fetish. Words which emerge absolutely in the encounters and relations of exploitation and violence that we're interested in; William Pietz’s work on the provenance of the fetish and the encounter between European and non-European peoples along the slave and gold coasts of West Africa from the late 1400s onwards.

And the work of Chris Pinney, James Elkins and many others on iconoclasm on what Bruno Latour calls ‘iconoclash’, in precisely its trans-cultural and cross- cultural sense. So, there's a challenge to language which I know we'll be talking about, as well as a language to political aesthetics. That's enough from me.

Dr Lisa Skogh: Well, thank you so much, Simon, for introducing the topic of today's salon. I would like to mention also that this series is sponsored by the British Academy, and I would like to thank them for their generous support, including British Academy Fellows, Lisbet Rausing, who could not be here today, and Simon Schaffer, who, together with Evelyn Welch, kindly endorsed the project.

And we would also like to thank our colleagues at the V&A for providing such a spectacular setting for these historic conversations, and especially I'd like to mention Professor Lesley Miller and Joanna Norman.

Before I introduce you to the three main speakers of today, I would also like to ask everyone in the room to say your name and institution, just very briefly, and do it around in a circle. And let me start. My name is Lisa Skogh, I'm from the V&A.

I'm Simon Schaffer, I'm from Cambridge.

Dr Lisa Skogh: Thank you all very much. Our first speaker this evening is José Ramón Marcaida, who is a Research Associate at the Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities, CRASSH, University of Cambridge. He's a historian of science, specialised in the intersections of art and science, and in the early modern Spanish and Spanish-American contexts.

His first book, 'Arte y ciencia en el Barroco español', from 2014, is the winner of the fourth Alfonso Pérez Sánchez Baroque Art International Award. And it explores the connections between natural history, collecting, and visual culture in the Spanish Baroque period.

His current book project is a study of the scientific and artistic cultures of ingenuity in the Spanish golden age.

Dr José Ramón Marcaida: Buenas tardes, good evening. It's really a pleasure to be here with you in this salon. And if think about this theme, Europe seen through non-European eyes, for someone like myself, working on the early history of their, let's say, Spanish/Portuguese - let's call it Iberian empires, this question poses many challenges at various levels.

One obvious challenge is the issue of the sources. Which sources made up these voices, these views, these non-European views about the world - especially when we consider the most dramatic effects of these imperial projects (think of exploitation, extermination, colonisation, imposition of religious belief, etcetera)?

So, this is an obvious challenge. Another question is, of course, the very old habit of thinking, of putting Europe, in a way, in this privileged position, in this dominating viewpoint, which allows us to see the rest of the world from this sort of vantage point. I couldn't help thinking of the famous anecdote of Albrecht Dürer, when he's presented with the treasures from Montezuma, in Brussels; when he talks about these are the most wonderful most objects of art he’s ever seen, and he mentions the ingenuity of the native Americans. But, in a way, even though these are highly praising words, he's in a way imposing their Old World, their European viewpoint, on these artworks. And, of course, then there's the final challenge which we are all aware here of: how to make a case of these questions, of these challenges, in the museum context?

And in my brief presentation, I'll be mentioning two examples from works from these wonderful European galleries. But in a way, to start off, one of the first things I was thinking about when I was asked to talk about this issue, non-

European views of Europe, I couldn't help thinking of the idea of “connected histories” of Subrahmanyam.

I couldn't help thinking of this idea of the “implicit understandings”, these collective and “implicit meanings” as well, talking of Mary Douglas’ work. But the first reference that came to mind is the book by Serge Gruzinski, 'The Four Parts of the World'. And in particular the opening statements there, when he uses this wonderful source, this writer, this mestizo writer Francisco Chimalpahin.

Which, in a way, gives us a great example of a view by a non-European of European affairs. Gruzinski makes a wonderful use of this author, who writes a diary in Mexico in his own language, in nahuatl. He's writing this diary, and in this diary he reflects on many of the events, and all the news that are coming from the Old World, which, in a way, gives us a great example of a view by a non-European of European affairs.

And let's keep this dichotomy, the New World and the old world, in mind, because I guess we will be talking about this dichotomy for a long time today. But anyway, Gruzinski makes a wonderful case of this author who is recording events coming from Europe as well as events at the local level, events in Mexico. And in a way it's a wonderful example because it shows that this is a case of circulation of news, circulation of information, circulation of people, circulation of materials.

And, of course, this is part of a bigger argument on Mexico, Central America, being one of the four parts of the world. So, this is a great way of, in a way, addressing the issue of Europe, this Old World, being just one of the four parts of the world. And I thought it was interesting to, in a way, think of Europe, think of visions of Europe, as part of this four-part system, which, of course, it's well- known to us.

But in a way, I don't think we've been addressing this issue of how Europe, in a way, it's at this moment being thought of as part of a much larger system. And in a way, my first example addresses this issue. It's an example, it's a bird, and it's an example from, in a way, the East Indies. Again, the West Indies/the East Indies dichotomy is something highly controversial. We can talk about it later.

But the idea that there is a bird, coming from the Spice Islands, which, in a way, becomes a sort of global object; an object that travels everywhere, but begins to make sense and has these wonderful associations in the Old World, in Europe. I'm talking about the birds of paradise, which originates from the Spice Islands, from the Moluccas. But it's transformed into this wonderful artefact that travels all over the world: it reaches America, for example, always dead, without feet. That's the key element of it. And I was, as a historian of science, I was always perplexed by how often this bird, coming from the East Indies, features in books of natural history on the West Indies, and in particular books on ‘materia medica’, of Mexico.

And now, I'm not surprised, in a way, because this, in a way, this bird is telling me the story of their multi-connections, all the transfers that link these settings. On the one hand, the Asian context, then the part of the world that is America, and of course, Africa on the way, and Europe. I could not help thinking of the reference of the first European explorers that arrive in the Spice Islands, and in a way, the bigger context of the South Asia ... The South Asia context. They are described, the early, the first Portuguese explorers, they are described as “Franks”, Feringgi, in the Malay language; “Franks” being this association with, in a way, inland, medieval, account of the Franks opposing the Muslims. And I couldn't help thinking of, for example, the first accounts of the explorers, Portuguese explorers, that arrive in these areas. They bring presents.

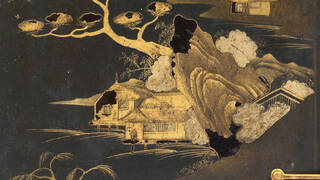

And the famous anecdote by Vasco da Gama, where he presents the local ruler with some presents and these are rejected because they're certainly not impressed by a cask of honey, a set of cloths and a bit of sugar. I mean, these are not the type of possessions you want to give a local ruler. So, in a way, this example, the bird of paradise which is present in a painting by Jan Brueghel the Elder, which, interestingly enough, represents the Garden of Eden.

The Garden of Eden was meant to be located in the New World and now, in this context we find the Garden of Eden located in a painting in the Old World. There, the birds of paradise, without legs, with legs, becomes a wonder, and in a way, this wonder becomes meaningful in Europe. It's a wonder, it’s a commodity that has been used for many centuries in this context, South Asian context. But it becomes a wonder and it becomes meaningful, in a way, as a novelty in the Old World.

My other ... sorry, now, wait; let's think of the ingeniousness of Europe. Let's think of the frankness, again, “Franks”, frankness of these accounts, the merchants that bring this novelty to the New World, to the Old World. And then my second example is, in a way ... it doesn't address directly the question of the non-European view. But I think it brings interesting connections of how exotic objects... “exotic” is a term that obviously needs much discussion, as well. It's a piece of pottery.

It's a piece of ceramics from Mexico, here [at the V&A] is described as a water cooling ceramics. It’s the “búcaro” piece from Mexico. These are wonderful materials, wonderful items that were produced in Mexico, later in Portugal; were used to cool water, to add flavour to water, and they're depicted in many still life paintings of the period.

They're also depicted in that major Old World, let's say “European icon” - to use Simon's reference to icons - that is Las Meninas. The princess in Las Meninas is being offered a búcaro to drink. But interestingly, the búcaro found another use. The búcaro was broken into pieces and was eaten for a cosmetic purpose. The eating of the búcaro will whiten your skin, and this was a method used by the Spanish ladies at the time to have a whiter skin.

So, I'm very interested in this connection between order and adornment, implied in the relation, in the words 'cosmos' and 'cosmetics'. This is a connection that I first learned through a colleague of mine, Juan Pimentel. Cosmos and cosmetics: I'm very interested in how cosmetics play a role in these galleries. To what extent are we displaying things to look in a certain way, and we're not presenting items - in this case, a broken búcaro into pieces - for the uses that we know they were used. So, in a way, my two final questions, my two final comments. One would be: to what extent we can continue to address the issue of Eurocentrism, and which has been addressed already, through our reflection of these shared, intercultural, these “connected stories”, this hybridity, these “implicit understandings”?

How can we address this issue in the context of the museum? And my second question to all, would be, in a way: to what extent cosmetics plays a role in the way we, today, are reflecting on the question of Europe? This is a space created by a Cuban collective, Los Carpinteros. We are in London. We're talking about Europe, non-European visions of the world, in a context where Europe is perceived now again as the new Garden of Eden, where people want to come. And what is the role of cosmetics in our European policies about it? Thank you.

Dr Lisa Skogh: Thank you so much, Jose. Our second speaker this evening is Anna Grasskamp. She received her PhD from Leiden University, with a dissertation on ‘Display Practices in Early Modern China and Europe’. Since 2013, she is postdoctoral fellow at the Cluster of Excellence, Asia and Europe in a Global Context, at Heidelberg University, where she has taught three seminars on artistic exchanges between East Asia and Europe.

And in 2015, Anna was a visiting postdoctoral research fellow at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, in Berlin. Her publications include ‘EurAsian Layers, Netherlandish Surfaces, and Early Modern Chinese Artefacts’ in the Rijksmuseum bulletin in 2015. As well as ‘Asia in your Window Frame, Museum Displays, Window Curators, and Dutch Asian Material Culture in World Art’. As well as ‘Frames of Appropriation, Foreign Artefacts on Display in Early Modern Europe and China’ in ‘Qing Encounters: Artistic Exchanges between China and the West’, published by the Getty in 2015.

Dr Anna Grasskamp: When we think of visions of Europe seen through non- European eyes, Dipesh Chakrabarty's 'Provincializing Europe' of 2000 immediately comes to mind - at least, to my mind. From this claim to provincialise Europe in terms of contemporary scholarship, it is only a tiny step, it seems, to early modern figures who actually had Europe provincialised in their intellectual, visual and material visions of the world.

One of them is Emperor Qianlong, who reigned China from 1735-1796. Qianlong’s staging of himself and his empire happened through a variety of conscious and controlled intellectual, visual and material interventions. As Taiwanese scholar Lai Yu-chih has shown, in the Emperor's conscious attempts to picture the empire, objects, motifs and styles from extra Chinese and in particular European origin, played crucial roles.

Inside and outside of Qianlong’s court, the eighteenth century in China is a century of Eurasian objects. Produced and exchanged within Eurasian spaces, Eurasian artefacts are entangled objects that are constituted of Asian as well as European material components and, if you like, visual identities in terms of motifs and styles.

A prime example, probably the prime example, of a Eurasian object is provided by a particular group of blue and white Chinese porcelain, also on show in the gallery, that is, until today, globally known under its Dutch name, kraakware, a term coined by the Dutch after conquering Portuguese carracks; kraak, in Dutch. And their precious goods from these carracks, among them crack porcelain in Asia, obviously.

The porcelain artefacts symbolise Dutch-Chinese trade relationships, as they embody dual cultures; Asian as well as European visual and material languages. An aspect that is often overlooked, however, is the fact that samples of this typical kraak ware were also found in tombs by members of the Chinese elite. As this illustrates, and in contrast to previous scholarship's findings, Eurasian objects were never, strictly speaking, export art.

Even among the apparently most clear-cut, export-oriented object types, for example, some of them currently on display, we find many that were consumed by local collectors in China itself. Another striking example of a Eurasian object shown in the V&A galleries is provided by the curved, freestanding sculpture of a European merchant, made in the important Chinese harbour city of Guangzhou. I'm not sure if all of you saw it; it's a tiny figure, it's this large.

And a box behind it, skilfully crafted box as well, made in this harbour city, Guangzhou. While Guangzhou products, such as this sculpture of a European merchant, strike us as modelled after European tastes and demands, being

European rather than Eurasian, let us never forget about the harbour city of Guangzhou, as a Eurasian space and briefly consider the absolutely significant amount of Guangzhou-produced wares made for the imperial court with striking European designs and motifs.

Among them, in particular, images of European women were copied, after Dutch prints and engravings to be modified and, if you like, pasted on the surfaces of enamelled vases, boxes, mugs or plates. Emperor Qianlong, the one I talked about in the beginning, who had Europe in a certain sense provincialised in his own visions of the world, himself being at the centre of his world view, possessed countless images of European or European-style women throughout his palaces.

In a similar way in which a European merchant, as the one on display here, could have his image carved in Guangzhou for so-called exports, and in similar ways in which European chinoiserie functioned as a visual China fantasy, also the Chinese Emperor had images of European people made, multiplied and distributed in his private realms.

While the European merchant would take a Chinese souvenir home, collecting the foreign in this way, the Chinese Emperor put fragments of the exotic - and we're going to talk about this term a little bit more - as well as fantasies on the exotic, on display, having foreign and foreign-style women figure prominently in his aesthetically-defined microcosm of power.

Until today, as most of you know, Qianlong's collection constitutes a large part of what is on display in the two Palace Museums in Beijing and Taipei. As a consequence, his collection as a vision of the world, as a microcosm, still defines canons of Chinese art on a worldwide scale until today.

The interactions between material and visual culture made in Western Europe with Chinese artefacts have been researched extensively under the labels of chinoiserie, exports or company art. Recent scholarship has drawn attention to the mediation of Netherlandish and Flemish art in Asia, for example, and developed terms such as ‘Eurasiarie’,’ Européenerie’ or Chinese ‘Occidenterie’ to label fashions for European and European-style art in China.

Going beyond sociological approaches that focus on European Jesuit agency in China or East India Company's mediation, and nuancing umbrella terms that stress the priority of man-made systems of taste over object agency, European objects can also be read as statements in themselves.

Rather than qualifying Eurasian objects according to their respective geographic origin as essentially European or Asian, or in relation to historic sequences as typical or representative of a certain period, a certain place, or a specific centuries' cultures, let us understand them as, "Caught up in recursive trajectories of repetition and pastiche, whose dense complexity makes them resistant to any particular moment."

And this quote is from Christopher Pinney, who has been brought up already. In many ways, these complex objects provincialise our own central need for one- sided readings and clear distinctions that are commonly at the heart of research perspectives on anything European or Asian.

Eurasian objects, as the ones on display at the V&A, or those possessed by Emperor Qianlong, entangle multiple material and visual layers. They function as souvenirs and tokens of conquests in systems of power. And the example of foreign women on display, playfully engaged with exotic as well as erotic systems of appropriation and othering, and objectification, while generating knowledge and new strategies of material and visual expression that we need to approach through new and collaborative kinds of Eurasian scholarship.

So, my questions with which I would like to finish are; how can we overcome simplifying readings of Eurasian objects and objectifications of the other, through new systems of Eurasian scholarship and collaboration in academia and museums? And how can we establish and develop the trans-cultural - or the Eurasian in that example, but doesn't have to be the Eurasian; the trans- cultural in general - as the new standard and as the new normal, as the new norm?

Dr Lisa Skogh: Our third speaker this evening is Daniela Bleichmar. She's Associate Professor of Art History and History at the University of Southern California. She was educated at Harvard University and got her PhD at Princeton University. Her work focuses on histories of knowledge production, cultural contact and exchange, collecting and display, and books and prints in early modern and the Spanish Americas.

She's the author of 'Visible Empire; Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment' and co-editor of three volumes on the histories of science, collecting and material mobility in cross-cultural contexts. Her current projects include a book on Mexican codices and early modern transatlantic knowledge, and the exhibition images of Latin American nature from Columbus to Darwin at the Huntington Library Art Collections and Botanical Gardens.

Associate Professor Daniela Bleichmar: Thank you so much, Lisa. Thank you for inviting me to present really a, you know, a non-European vision of these questions. So, like Simon, I was thinking about what categories we bring to these questions, and the one that I wanted to put on the table is the idea of translation. And I am thinking about the first dictionary of the European vernacular, Sebastián de Covarrubias’ ‘Tesoro de la lengua castellana’ from 1611, where the word translation has two main meanings.

The first one, the one we normally think of, to move something from a text from one language to another. But the second language, to physically move an object from one place to another. And there's a very closely related meaning, which means to copy something. So, these ideas of both reinterpretation, of physical mobility, of reproduction, the idea that movement implies transformation.

And how to use this to think about the question we're examining today. The visual and the material are involved in a process of translation between the Americas and Europe from the very beginning. The early contact between Europeans and Native Americans involves a real tsunami of images, which Serge Gruzinski has called a war of images, in which gods are translated into idols.

They need to be destroyed and replaced with categories like art and religion. And in early encounters, Europeans had triggered great power to American visual and material culture. It is the work of the devil, it is idolatrous, it is disturbing, it needs to be eradicated. On the other hand, Amerindians often find European visual and material culture often inefficient, uninteresting and powerless.

There's a famous story of the initial encounter between the Inca Atahualpa and Pizarro, in which Atahualpa presented with a book and told this the word of god, finds it a moot object and doesn't speak and throws it to the ground. And part of this has to do with different conceptions of how visual and material culture work and what they do.

So, versus the European concept of representation of images showing something, we can think of Nahua ixiptlav, the temporary incarnation of a divine being in a human or animal form, or the Inca idea of material embodiment.

Images and objects are not showing something, they are being something. And for these two cultures, and so they are inherently more powerful to Amerindians than mere science. And there's a constant translation of American categories by Europeans. The earliest ones are through the lens of the Reconquista, by which Aztec temples are described as misquitas or mosques.

Priests, Aztec priests, are rendered into ‘alfaquias’ or priests from other religions. And there's a very, very quick understanding on the hand of native makers of the importance of translation and so we have, for example, their 1577 Florentine Codex, a twelve-volume encyclopaedia of Aztec culture, in which the first book, The Book of the Gods, inscribes each Aztec code as ‘otro Hércules’; another Hercules. ‘Otro Júpiter’; another Jupiter. Translating, understanding what the categories that count are; antiquity, classical and translating Aztecs into other Greeks.

Another idea that I wanted to bring to the table is a question of flows and frictions. The idea that in this attention to movements, we should also be thinking about what moves and what doesn't, what moves easily and what sticks, and what things travel with an object, and what things are lost, shed, ignored or translated because many of these categories change over time.

So what is European in Mexico in 1521, is very different from - or how to say - what the Virgin is in Mexico in 1521 is a European image. When the Virgin is in Mexico in 1648, it's a Mexican image, it's not a European image.

So, the categories are not stable over time. So, what I wanted to close with; my question was how do we think about the instability of these categories, both geographical and chronological, about what is Europe, where is Europe? I know this has been discussed, but this is a moving target, four different regions in different ways.

And also about the periodisation, right? These galleries are 1600 to1815, but if I'm thinking about the Americas, I just cannot start in 1600. I have to start in 1492, in 1521. The periodisation is completely different, so I also wanted to put that on the table for discussion. Thank you.

Professor Simon Schaffer: Okay, so there's an enormous amount to talk about there. We had a series of questions, remember. There are questions about the function of museums, curatorship, museology, and the role of those kinds of institutions and collaborative institutions in making what Anna called trans-cultural approaches the new normal. Loving that phrase.

Secondly, it's very interesting to think what kinds of objects, what kinds of materials, seem to be peculiarly eloquent, if this is the topic of conversation. Birds of paradise, cosmetic, or cosmological, jars, codices, kraaks, porcelain and so on.

Are there classes of objects that, as it were, are peculiarly telling? Which would imply that there are classes of objects that are not. And I wonder what they would be? So, finally, just as a summary, perhaps, slightly more provocative, all three presentations and no doubt much of our concern centres on issues of hybridity, of mestizaje, and is that a good and effective way of thinking about, for example, the materiality of the cross-cultural and the trans-cultural?

It might be, it might not be, particularly in the context of these galleries. And no doubt what goes along with that was Daniela's closing comments, both the incommensurability of chronologies, which I think is extremely interesting ... I mean, if one thinks not just of the Americas but of the Middle Kingdom, 1600 to 1815 does not cut the world at its joints at all.

It transgresses the boundaries between dynasties and reigns in all sorts of ways that might do justice to what we need to get at. If one includes African material or, above all, Oceanic material, the chronology is even weirder, frankly. So, that might be a set of issues to think about.

And finally, just to strike a more ethnocentric note, don't homogenise Europe in this conversation. One of the points of the two previous salons, was to heterologonise and hybridise the notion of the European, and it would be a shame if we now reverted to a stereotypical image of Europe as the one to be contrasted with what others see here. Okay, the floor is open. Can I just say, can you, when you first speak, just give your name, which will help us on the recording and on editing?

Dr William Kynan-Wilson: William Kynan-Wilson, Aalborg University. I'm going to have to use the problematic label of non-European, just for the moment. But this question, Europe through non-European eyes, it moves away from a Eurocentric point to an extent, but it also assumes that non-Europeans were looking at Europe.

And so I'd just like to raise the issue of when were non-Europeans looking at Europe, in what context, when and why? And in thinking about that, I think of Ottoman collecting habits and the Topkapı Palace as an incredible collection of Western clocks and mechanised instruments. There are stories such as Thomas Dallam, an Englishman travelling to Constantinople with an organ for the Sultan.

And so technology is an interesting thing where the Ottomans clearly are looking towards Western Europe. But if we think about poetry and literature, miniatures and tiles, Persia is the place that the Ottoman world is really looking at, at least around 1600. Perhaps it changes. And equally, China and Chinese porcelain.

There's an incredible collection that the Sultans amassed. So, I'd just like to raise the issue of when are non-European peoples looking at Europe, and when are they not, and what are the contexts around that?

Dr Philip Mansel: Philip Mansel. Yes, I agree about ... or, for example, the Ottoman Empire, it's looking both to Persia and to Europe, and Persia also. And the question 'where is Europe?', well, one place Europe was, was surely Rome. The Catholic Church and the teaching orders of the Catholic Church, which spread really round the world.

And that shows some non-Europeans' fascination with the knowledge brought by Europe; books, translations, astronomy in the case of China, the Chinese court. Siam and Louis XIV, they are fascinated by what Louis XIV's embassies have to bring, and particularly trade. They're much less welcoming to Louis XIV's plans to take Siam over, which end in catastrophe in 1687-8.

And another place that represented Europe in my opinion was Paris. You can see in the galleries here, the role of Louis XIV and the [unclear]. That also has appeal in Peking, in the French teaching orders who start to make some Greek Orthodox Arabs, Greek Catholic in Aleppo and Damascus in the early Eighteenth Century.

And Paris's role in bringing education is hugely important in the Nineteenth Century when young Turks regard it as a centre of light and modernity and freedom, compared to their own empire.

Dr Lindsay Allen: Lindsay Allen, King's College, London. I think just a quick interjection on when do non-Europeans look at Europe; in some of the material I've been looking at, it's almost that the Europeans are trying to catch the gaze of the non-Europeans in order to reap the advantage of that. So that when Charles I sends an embassy, or his own sort of personal embassy rather than the East India Company, to Persia, he sends portraits of himself and his family.

And not only that, but that's partly in response ... these are in the hands of an artist, who is supposed to go and cultivate the favour of the court and sort of win over the king there. So, there's a sort of traffic of representation going on as part of the dialogue, I think, between these two places. And it's almost part of a string of different courts to which these ambassadors were sent to try and cultivate favour.

So, often these guys would go back via Moscow and Saint Petersburg and Vienna as well, and so they would try to cultivate the same kind of favour in each place. So, there was rather these gradations of the flow of different non- Europe to Europe. I mean, let's have an argument about where Europe ends, and that [unclear] of Persia to Moscow. That's all I have to say now.

Dr Michael Bycroft: Michael Bycroft, University of Warwick. I was going to ask the question which is almost the opposite of the first one. Which is when were Europeans in early modern Europe trying to imagine themselves as non- Europeans looking at Europe through non-European eyes? Which, after all, is what most of us are doing here today, because most of us, or at least I am, are European. And I'm trying to look at Europe through non-European eyes by imagining non-Europeans. And I can answer that question, sort of, for the early eighteenth century, for intellectual history.

So, if you look at ... try to think of a list of authors in Europe who were doing what I just said, look at Voltaire. His book, 'Micromégas', which is an attempt to imagine what the Earth would look like if you were a giant a hundred times taller than us. What would we look like? Or Montesquieu's ‘Persian Letters’, or Jonathan Swift's ‘Gulliver's Travels’. They're all about imagining yourself as someone completely different, and then coming back home and imagining what that would be like.

And you even get people, philosophers, like John Locke and his “Essay on Human Understanding”. There's a passage where he imagines himself as the ambassador of the King of Siam, coming to England and seeing a frozen lake. What does that tell us about the importance of experience, past experience, in making judgements about new observations? So, my question is do you find the same sort of thing happening in the form of objects? I've just cited a bunch of books where Europeans are looking at themselves from the outside. Is the same thing happening in the form of objects? That is a question for museum curators and people with experiences of early modern objects. That is a Eurocentric way of asking the question about non-Europeans.

Ms Mei Mei Rado: Europe in the non-European eyes, in China there was not such a concrete geographic idea of Europe until the second half of the Nineteenth Century. But there was this term, xiyang, literally translated as Western Ocean, in Chinese idea. But it's a very flexible term. In the Ming dynasty, it referred to the South Asian Sea.

But by the Eighteenth Century, it primarily referred to Europe. But at the same time, the European colonial territories in South Asian Sea can also be called xiyang. Like Doha in India was referred as small xiyang, ...................... xiyang. The goods brought by European countries to China can be referred - from the South Asian Sea - could be referred as goods from Western Ocean as well. So, this idea of Europe did not exist until the second half of the nineteenth century.

And also, I have comments on Anna's thought. Anna did a very good job to propose this, Europe played a part in the geographied imagination of the Qing empire. I'd like to add this temporal aspect; the Europe imagined in the Qing dynasties was also removed from its historical time and historical context.

Europe is imagined as timeless, distant countries, in the way participating in this Qing empire's construction of its universal identities.

Dr Danielle Thom: Danielle Thom, V&A. I would like to pick up on Jose's point about cosmetics, which I think is a very interesting one, in that something so seemingly trivial and ephemeral can open up huge questions about notions of identity and acceptability. In particular, I think it provokes the question, which I know we have approached somewhat in the first salon, about the degree to which the category of being European or non-European maps onto race.

Because with the question of cosmetics in this period in particular, what you were talking about in many ways is whiteness, the use of lead ceruse to whiten the faces, as was fashionable for women and some men, particularly in courtly and elite circles. And not wanting to treat Europe in a homogenous way, this is a particularly, but not exclusively, a Western and Northern European thing. So, when we talk about people who are non-European, are we talking about people who are geographically located outside Europe?

When lies the, for example, people who have been brought to Europe in an enslaved capacity or who have come as non-European merchants who find themselves in Europe? Do they become European by virtue of their presence? Or do they remain forever non-European by virtue of their physical markers of difference, their non-whiteness from the European norm?

Dr Tessa Murdoch: Tessa Murdoch, V&A. I'd like to pick up from the English colonies and to focus in on Charleston, which, by the mid-Eighteenth Century was the fourth largest city in British America. And to focus particularly on the black population, about 50% of the population in Charleston then was black. And to look at the objects that were being customised for that culture, to focus in on a particular object that was advertised in the South Carolina Gazette in March, 1762 by Joshua Lockwood, presumably a British clockmaker.

It's an eight-day clock. It has a hunt in the face with a buck, dogs and sportsmen, seen all in full chase as natural as the thing itself. But customised with a slave planting in the arch, and the motto, "Success to the planters." The face, the clock was invented by Joshua Lockwood in Charleston. But it demonstrates the way in which European skills were being customised for consumption in the new world.

Dr Anna Grasskam: Yes, I had a response to the comment before that last comment, but maybe we can return to your contribution. Can we do away with the term non-European? Because, to what extent is Qianlong Chinese, and to what extent is he European? And if we consider European as like a certain capability of handling European taste or manipulating European objects, surfaces, whatever else, then is Qianlong maybe ... or the craftsmen that work for him, as fluent and as European as some of the European craftsmen?

And Augustus of Saxony, the biggest collector of Chinese porcelain, is he Asian or is he then non-European? And I would like to ask, yeah, can we do away with the term non-European altogether, maybe?

DANIELA BLEICHMAR: That sounds, you know, seditious in the context of the European galleries, but that is exactly the point that I was trying to make, by saying, you know, what happens when you look at the Spanish Americas in the period that you're looking at, 1600-1815, where it's oil painting that is Catholic, that is virgins and saints. I mean, you know, this is Mexican art, this is Peruvian art. And this category is not really helping.

I guess I want to connect this to a point that you made, Anna, about the importance of the place of origin, the way that the place of manufacture ends up having ... being privileged much more than the places of transit or the places where things end, and this seems to me particularly important in a museum, because this is where all these things came to stay.

And I am thinking of the role of the Spanish Americas in these galleries, which would be very different if we were looking at the Europe 1600-1815 galleries elsewhere in Europe, not in London. But this textile, that is Chinese silk, that is sent to Mexico and then from Mexico goes to Peru where it is created into a textile that has a unicorn, mermaids, a Chinese dragon and Andean animals.

And then somehow ends up here, right. There's dot-dot-dot-dot-dot, right, like how it ended up here is part of the biography of this object. Is this, you know, like what label, right? You had - the curators here - you had to write these labels, right? What kind of object is it that is Chinese? And there's cochineal in the dye, right, which is an American product but it's really a Mexican product.

So that you have Chinese silk, Mexican dye, Peruvian makers with figures from everywhere. Like, where is this object from and why are we privileging the place where it was made?

Dr Marta Ajmar: Marta Ajmar, V&A. I think that this question of origin can be perhaps also complicated in terms of thinking not only what is this object from and therefore how do we label it in terms of geographical and therefore kind of cultural location, but from when is this object? Because temporality, in questions of periodisation I would say are very, very strongly intermingled. And in a way, the question that you and Anna posed can be connected.

In a sense that, for example, if we add into the mix the question of technological knowledge, then pretty much none of the technology that we see represented in material form in these galleries could have existed without a model for a technological transmission that is intrinsically multicultural and it's also something that can only be explained over very long periods of time.

Whereby, for example, just to return to your example of the Chinese Delftware or Delftware kept in Chinese collections, if we were to unpack it, technologically, then we have a technology that cannot be explained without Chinese porcelain, but it cannot be explained without Islamic tin-glazed earthenware. The vitrification on top of it is possibly a Mesopotamic technology.

And all these different layers and this technological complexity that co-exists in the same object makes explode in the ideas of puritisation, as coming in the linear form. You know, here, the paradox, in a way, is that the vitrification on the outside layer is the oldest of them all. And this in terms, really, I think, complicates this question of teasing out geographically and temporally the so- called identity of an object.

Dr Philip Mansel: Another example of where is Europe, what is Europe, and one of the great patrons in the new galleries is obviously Catherine the Great. And a clear example of somebody turning to what he calls Europe is Peter the Great, founding Saint Petersburg, specifically as a European city, breaking with traditional Russia. And part of it is, of course, making women wear modern European dress and having European make-up.

And I think this idea of, again, I come back to cities, Saint Petersburg is specifically intended to be a European city and it's partly based on his travels to London and Amsterdam. In fact, part of it is called New Holland. And later there's French culture.

Dr Christine Guth: Christine Guth - I'd like to pick up on a couple of themes that have come up, one of them about the use of the term Europe, and the other about translation. Anna said, "Well, can we do away with the term non- European?" But we might also want to question the degree to which it's appropriate to ask about the perceptions of, say, Japanese or Chinese or the Ottomans of Europe.

And let me speak for a moment from the perspective of Japan; the idea of Europe came extremely late, as it did in China, and the first contacts were, of course, with Portuguese and Spaniards. And we now very often understand that they were referred to as Namban, meaning southern barbarian; a term that didn't refer to their nationality but that referred to the fact that they came from the south, via Batavia.

But, to pick up on Anna Grasskamp's comment about historical revisionism, well, it now turns out that this term which we had long assumed had been very much in play in early modern Japan, turns out to have been popularised since the 1920s by scholars who were trying to emphasis the division, to create kind of binaries between us and them.

So, that's just one term. I - let me - just wanted to pick up two other terms that I think are relevant to this conversation. In terms of material culture, the kinds of ambiguities of identifying things that come from other parts of the world, is implicit in the term karamono, which means collectively things Chinese. And there are lots of representations of stores selling karamono in Japan.

And what they contain is things from China as well as from, say, glass, from parts of Europe. And many other things. They are a mish-mash. So, the point that I want to make about the word karamono is that in Japan, in early modern times, as in Europe, a lot of the rest of the world was reduced to a single kind of homogeneous term, a catchall for a wide range of heterogeneous people and things.

Professor Bill Sherman: Thank you. Can we do away with the term non- European? I would like to, because every time I come to the airport I have to go down the non-European avenue. And I wonder if there's, just as Michael was talking about, the way we can think about books imagining ... a difference between how books imagine and how objects imagine, in a way.

I just wonder, when we think about people and objects, citizenship is a massive issue for the European and non-Europeans. So, you know, in some ways those categories mattered then and matter now, hugely. And again, every time I have to get out my American passport and justify my presence and in fact my income in this country, that comes up. But how does it matter for objects, I think?

Well, in what ways does non-European as a category matter in the material world or in, in the object world. And I would be curious to hear if people have interesting explanations.

Ms Avalon Fotheringham: On the inverse of that, one of the interesting terms I've come across - sorry, Avalon - reading about the Indian perception of Europe and Europeans, again, like China and Japan, the concept of Europe as a geography doesn't come until very late. But the first impressions, some scholars put into a class of Europeans without Europe, there's a perception really just of the people and the objects that they are bringing, without too much concern about the geographies from which they come.

So, the question of what is a non-European object, what is a European object, how is Europe representing itself through these wonders that it's bringing very much for the purpose of making introductions and enabling trade? What are we trying, or what was, rather, what was Europe trying to say about itself? How is it representing itself in order to do that through objects?

Dr Lisa Skogh: In reference to the topic about non-European, and in light of collecting history in the early modern period, if I take the example of Rudolf II's post-mortem inventory from 1607, it's interesting to see that all so-called non- European objects, whether they are from Africa, from the Far East or from the so-called new world, they are called Indianische.

If you look in French inventories of the same time period or in other ... or in Italian, these objects are often called l’indienne that's something to think about, that are we talking here about foreignness and our perception in categorising that? Whether it's our interest in general to try to categorise.

Whether it's like writing a book; you have to start and end somewhere, as with the gallery, you have to start somewhere and you have to end somewhere, and you have to take these decisions. The same goes with the early moderns, and I think that is something to think about. And also in reference to what Philip was talking about and Christine, about Japan and Russia, the concept of the foreign from a Russian perspective was a German. And still today that word is used, Nemetsky.

Dr José Ramón Marcaida: If I can add to that, in many ways, many Southern European countries, with respect to Northern European powers, are also regarded as the Indians of Europe. Spain was regarded as ... the Spanish were regarded as the Indians of Europe, which brings me to another question which is the question of naming. So, we're talking about objects and their labels, but something that is on top of this is the question of using names and language.

So, the idea of how can you just name a new land New Spain, for example. Or the new island, call it Espanola. In a way, by naming, by putting these names, you're imposing the set of author, power, et cetera. But you're also, in a way, equalling and putting a contrast but also a correspondence between these old categories, these old places, and these new realities.

By naming a location in Mexico, Central America, New Spain, in a way we are bringing some older ... we are bringing some old terms, old classification, old schemes into these new realities. So, the use of names and the way names ... I mean, we've been making reference to labels in inventories. How many times we see Mexican items described as Chinese, for example?

Or Indians, or many of these items are referred to as exotic. But with this very specific label. So, in the name, we have a sort of idea of the ambiguity of the location, but in the name also we have a way of imposing sort of a category, a preliminary category at least.

Prof Margot Finn: Margot Finn. I've got two points. One's to pick up your point about naming and the other's to go back to Bill's on the problem of citizenship and whether we can talk meaningfully about citizenships of objects vis-à-vis citizenships of persons. But let me start with naming. So, I work on the East India Company.

And one of the things that is striking in my eighteenth century and nineteenth century sources is the number of my English and Scottish men or women in the East India Company world who refer to themselves in India as European; a term they would not be caught dead using in referring to themselves when they're in Britain.

So, I think that the naming in the East India Company context, which is in which Europeanness is hybrid, it becomes the choice of other ... the term of choice, precisely to separate them from those Indians, those Chinese, those other persons. But the moment they're on the East India Company ship back home, they are becoming British and English and Scottish, and refusing their Europeanness.

So, that's my point about naming. To go back to Bill's point about citizenship, there's a wonderful book by a US-based anthropologist whose surname is Ong, O-N-G, and she wrote a wonderful book called ‘Flexible Citizenship’, which she wrote just at the point before Hong Kong went back to the Chinese. And it's a study of the ways in which Hong Kong Chinese families prior to the handover dispersed their families globally in order to participate in as many legal citizenship regimes as they could.

Gaining ... one nephew might gain citizenship status in Canada, in Vancouver, and thus an ability to bring family members over and gain Canadianness for them whilst his brother might go to Britain and gain an entitlement in Britain. And this is a global phenomenon in many ways. Now, citizenship for persons is partly a matter of birth, which I'm going to make a terrible analogy here, which you're going to now destroy.

If we think of the birth or the manufacturing of an object, so we might think about birth as one of the ways of creating this identity, and yet citizenship is also a juridical status that one can gain by going to Vancouver, by going to these other places. So, these kind of trans-cultural translations, to go back to your point, which are movements, are also ways of changing citizenship.

But once one is instantiated in a particular citizenship regime, one can reproduce other new persons that possibly are born to having that citizenship status. So, perhaps we can think through the different modalities, mechanisms, regimes, that give the different kinds of citizenship, and whether there are any analogies more meaningful than the completely specious one I've just used.

Dr Beth McKillop: I think it's great to talk in these galleries, called the Europe Galleries, about European and non-European and to think in this museum of how we have categorised our collections and presented them to the public and to scholars. I'm Beth McKillop. And I wonder if everyone in the room is conscious of a kind of intellectual approach to the dispersal of the collections around rooms in this museum.

Where the lower galleries are thematic, sometimes called cultural, and the upper galleries are conceptualised as technical and more focused on process. And I think it's very important to be conscious as we sit in these galleries that they are going to provide for a generation of visitors, families, children, a visual picture of the history of Europe.

And it's a big responsibility because we know that many of our non-academic visitors, if I can put them like that, those who haven't a serious scholarly interest in our subjects, are going to overlay what we show with the ideas of the modern nation state. And that's a real danger for us, because everything that we have to do is so compressed in its moment of encounter with the visitor.

And I think that this kind of event and its dissemination, perhaps online, and I hope in other ways, can help to give a bit of texture and a bit of pause to the fast visitor, and I hope to the students of the future who are going to come through these visitors as children or as young people, and one hopes be taken in a longer journey.

So, I think, I really welcome this complication of the simple naming that we are forced by practicality to undertake in presenting galleries like this, and which Lesley, as the curator of the galleries, is hugely conscious of.

Dr Tessa Murdoch: Tessa Murdoch again, from the V&A. I just wanted to focus from cosmetic to exotica and I think one of the vibrant experiences of the new European galleries and indeed the British galleries above is this extraordinary sense of colour. And I'd like to refer again to the sources of the principal dyes. We've heard about cochineal, and I'd like to mention the importance of indigo, which was used in naval uniforms and again, from South Carolina.

But then I'd also like to conjure up that wonderful picture of the bird of paradise and the wonderful trade in exotic feathers, and to remind you of some of those extraordinary confections that were made out of weaving together exotic feathers and a certain great bed which is in the [unclear] Palace in, I think, in Potsdam, that was actually complied and woven by Huguenot merchants in Putney, London, for that market. So, there we have a world picture but a very colourful one. Thank you.

Prof Simon Schaffer: Hi, Simon Schaffer. I think that what's just been said is really, really valuable. Two thoughts occur to me. One is so it would be - going back to Anna's demand - it would be really, really useful and helpful to take as seriously as I know museum curators do, the many different ways in which objects and material culture were appropriated in the period covered by the galleries, by people not from Europe.

You see the way I didn't use non-European there? And what comes to mind immediately is a really important text which I think illuminates the museological dilemma a lot, which is a text by Marshall Sahlins called ‘Cosmologies of Capitalism’; the Evans-Pritchard lectures given in the late 1960s. Sahlins' argument there is that we very often - and he's right - we very often make the following mistake: We suppose that there are enormous cultural variants in taste for and demand for suites of objects. But we assume that there's a universal, which is capitalist appropriation. So, we note the way in which the goods from the south are highly desirable, so there is a market for them. We note the way in which Indian things are much sought after, though, so there is a market for them.

But one of the things you see wonderfully well in the V&A is the enormous cultural variants in the mode of desire. The example that Sahlins offers is exactly in the period covered by this gallery, and treats almost none of the objects which are in the gallery because he's an anthropologist who works in the Pacific. So, his examples are taken from Hawaii and the Kwakwaka'wakw, from what the Canadians call the Pacific Northwest, bizarrely.

And from Qing China, and he points out the ways in which those three regimes in Beijing, in Hawaii and along the Canadian Pacific Coast, treated goods that were exotic for them in completely different ways. Perhaps as tribute, perhaps as something to be given away in a potlatch.

Perhaps something to be appropriated and rendered the same as the lineage, as in the case of the Hawaiian kings, who take the fact that the colour red is so pervasive on British merchant vessels and incorporate it into the cosmetic cosmology of red, which plays such a crucial role Polynesian culture.

But the modes of appropriation are variable as well as the notion of the exotic. And it seems to me if we're to address this fundamental question, can we make the trans-cultural the new normal, and how can museology contribute to that? That's a way in which it can contribute to that because it's an extraordinary resource for showing the relativity of expressing desire and the modes in which appropriation is executed. And I think a lot of the conversation absolutely illuminates that issue.

Associate Prof Daniela Bleichmar: That was super-useful and I think that we should think not only about the success ... the variants of reactions involves not only the successes but the failures. The things that are not appreciated, the things that are not consumed, not imitated, and when I was looking at the section on ballooning, I was thinking of sort of my favourite study of ballooning, which is by Jane Murphy who's a historian of Arabic science who looks at the answer to the l’Institut d'Egypte and the French science as viewed by Egyptian scholars and the episode in which the French decide they're going to impress with their technology and try to launch a balloon, which fails and so all the Egyptian scholars embarrassedly leave. And then when they finally floated, how the Egyptian scholars are so ... they don't know how to react, because this is not impressive, mathematics impressive.

This, they compare to when a servant flies a kite, right. It's like for children. And so that is a, you know, magnificent failure, but the idea that, you know, in this ... I was thinking about citizenship and this object and sort of diasporic objects. Which of them do well and which of them don't, I think is really interesting. So when you were talking about the realities of the museum curator and of the visitor coming through, as I was coming through today I was really trying to think, well, what are all these visitors taking?

And I was with a friend, and when we left I said, "So, what was Europe 1600- 1815?" And she said, "Rich people had lots of beautiful things." And I wonder whether one thing that you may incorporate are these voices that are talking back to the objects, and expressing diverse viewpoints, right? The people who were impressed by the balloons and the people who weren't, the people who loved the clocks and the people who found that, you know, they broke down, they didn't work for anything.

Better melt, you know, the metal or whatever it was. But that ... not everything was a success, I guess is the point.

Dr Lindsay Allen: I just have one quick question I guess to put to all the curators in the room as well - this is Lindsay again - to answer that question of how do we make trans-cultural the new normal, is one way of doing that to be more transparent about the modern object biography of everything in the gallery? Because this cropped up in my head just as Anna brought up this wonderful Peruvian textile made with Chinese silk, of which a very similar example was recently in Boston, I think, on display.

And I was thinking is that part of the same textile? How did that textile get here? How was that textile there? So, that one is at least in the Americas, but this one is over here and it's a smart piece. So, if we talked, this idea of incorporating diversion, voices and speaking back to the story of Europe, this hermetic system of Europe between these dates, is actually by talking about all the messy edges of these objects and how they've got to the museum.

But that unfortunately does complicate the curator's job, so I'm asking is that reasonable or is that crazy?

Ms Joanna Norman: Joanna Norman from the V&A. Yes. This is one curator speaking, not all. As various people have pointed out, it is complicated because there are so many layers of meaning in just about every single object of the 1,100 that we have in these galleries. And as you very rightly pointed out, Daniela, we can only say ... we have 60 words on a label in which to give any kind of commentary.

So, although we have other means at our disposal, where we can use the ... search the collections online, we can add to catalogue records, we can explore things in publications, in blogs, it's very difficult to actually do it within the context of a gallery display. And similarly, in terms of the modern object biographies, that's also very difficult to convey because you'll have noticed on label strips, you have about this much space to deal with the origin, which is in itself problematic, a sense of designer or manufacturer, which is often problematic, materials ...

And then you get onto actually the modern biography of the object and how it came to be in the museum. And also there's the added complication that often that piece of history is very lacking in detail. We assume that - or it's often assumed, I think - that we know everything that there is to know about how things came to be here, but we really don't.

And so the edges, as you say, are very messy. And it is quite a big challenge to actually convey any of that sense of messiness within the way that visitors experience the objects in the galleries themselves.

Dr Olivia Horsfall Turner: I'm Olivia Horsfall Turner. As an architectural historian, I've been thinking about that group of objects, large objects, which don't fit inside the museum at all, apart from this wonderful structure that we're sitting in. But, you know, buildings are such an important part of not only private realm but public realm, and finding a way to represent those within the museum setting is hugely challenging.

Trying to rise to Simon's invitation to think of objects that are eloquent about some of the issues that we've been thinking about, I was ... and which also I think an example that speaks to the breaking down of European, other than European, outside European, non-European, if we venture to use that again. But there's, instances in the 1600s where architects are travelling abroad, using networks through the Royal Society as well, to travel, for instance, to Istanbul, which, as we've discussed before, might or might not be considered within Europe or outside Europe. And they're travelling there to look at centrally- planned buildings, to look at centrally-planned churches. To rediscover not another history but their own history. So there, an example where there aren't these boundaries, there's not a sense of us an them. This is actually people from, you know, inside England, which, as we've discussed, might or might not be, at different points, inside Europe.

And going to rediscover themselves at a different point in time, that there's a sense of travelling somewhere different, to go to a different period of history as well, and not treating the primitive as something which is idealised, fetishised, but which has some objective truth about it, and thereby to rediscover themselves.

And so we have appropriation, a cultural appropriation, perhaps, in one view. But actually a re-appropriation of one's own identity, because that identity survives in another manifestation, in a different place, at the same time.

Prof Simon Schaffer: We've run out of time. Let's give the three speakers each a chance to respond, starting with Jose.

Dr José Ramón Marcaida: Very, very quickly, I think my, in a way, conclusion out of this conversation is that we should stick to mess and complication. I completely sympathise with the team of curators, and both in these galleries ... But let's keep in mind the other side. So, we have mess, complication, but then we have the temptation of order and this reference that I made to appearances and cosmetics to make things look beautiful, interesting and innocent, in a way.

So, are we interested in the complete object or are we interested in the broken pieces? In a way, there is interesting tension here in the broken pieces.

Dr Anna Grasskamp: I couldn't agree more on the messiness and I would love to stick with the messiness as well, because messiness is a chance also. And I think identity is a mess, or finding identity is a mess for objects, for citizens, for people, for people from Europe from people who are born outside of Europe. And yeah, as you've said, Jose, as well, I mean, the museum as a frame tries to imply order and work against this messiness and there are limits to this order.

And relating to the idea that we had of object citizenship and so on, objects have power and objects can transcend boundaries. I think that's pretty clear. But they can also subvert certain orders and messiness has this power to subvert certain orders and I was wondering what then is the object passport and if the object passport is the label, if that is the passport then you're writing it and we are writing it.

Associate Prof Daniela Bleichmar: Okay. I guess there's been lots of wonderful ideas and to conclude with I think complication is always a scholar's temptation. Although I understand it might not be, you know, part of the curatorial mission or of the visitors' desired experience, because people come to a museum to see things and to leave with ideas about what they saw.

And I guess that what I think is that the visit is not only a conversation with a object, and with a curator who has placed the object there, but also with the past. And with the categories and the preoccupations of the past, and something that a lot of people brought up, it's the categories like European, were not active in this period. There were many ways to think about geography.

And while, Bill, I really, you know, personally share your practical problems with moving places and citizenship, if you think travelling with an American passport is bad, you know, don't travel with mine. But the concept of citizenship is one that emerges towards the end of this period, right. Citizens are invented in the, you know, last quarter of the eighteenth century.

And so I think that is part of helping visitors visit the past, bringing the period ideas about place, about movement, about materiality, in 60 words or less, however you do that. But to really keep the historical moment that you are materially capturing here as part of the sort of intellectual takeaway of the galleries.

Prof Simon Schaffer: Thanks a million to everybody. A few closing thoughts, then. One is so we like messiness, we like hybridity, we like mestizaje. That is, remember, while quite infeasible for anybody, except the genius curators who work in this museum, to put on a label. It is, after all, an extremely edgy political lesson.

The Prime Minister of this country, a country which, Daniela, still doesn't acknowledge the notion of citizenship. We're subjects here. We're not citizens. The Prime Minister of this country thinks that it works if you describe a group of refugees as, and I quote, "A bunch of migrants." And it would be salutary, it seems to me, if, on the entrance signage on this gallery, it said, "Europe 1600- 1815, a bunch of migrants."

That's four extra words, I know it would be difficult. But I think it would be a welcome intervention and I'm sure you could get cross-cultural sponsorship for the enormous expense of changing the four signs. Second, it's a very familiar point both for our curatorial friends and for scholars and researchers, that there is a kind of professional deformation in favour of the study of and celebration of invention, rather than, or at least much more than, tracing the object biography, tracing adoption, use, fate, disappearance, and recovery. One way of doing that, and the V&A does that a lot, is constantly to reframe its collections. This is not the only way of framing this material. We were, helpfully, I think, reminded of the implicit geography, topography, of the various rooms in this building.

Interesting too, then, for us, to think about, for example, where is Japan in the London museums? Here, are you sure? Has its own room, guys. But also the British Museum. But there are some cultures that only exist here and not in the British Museum. And there are some cultures that only exist in the British Museum, like America, which doesn’t exist here at all - yet.

So, those kinds of triage obviously have an ancestry. It's fascinating to think about those ancestries. We've been reminded that they're patchily documented, very often. And extraordinarily patchily documented in some cases. The fate of the Museum of Mankind collections, the origin and provenance of the India Museum, and so on, are really good examples.

That's probably enough. I just wanted to remind you of the future, the final of the four Salons is next month, on March the 9th. And almost, but not quite as though it had been planned, the theme of the final salon is Ephemeral Europe, and Mike's going to talk. And Tina Asmussen is going to talk. And Elaine Tierney is going to talk to us, so I hope many if not all of you can come.

LISA SKOGH: Thank you, Simon. But most of all, thanks to all of you here and to our three main speakers; Anna, Daniela and Jose. Let's give them a round of applause. Thank you.

Thank you for listening to What was Europe? A New Salon. We would also like to thank the British Academy for generously supporting this new Salon series. In the next Salon our journey into the past continues with the last of our four British Academy funded conversations about Europe. And this time the topic will be on ephemeral Europe 1600-1815. We hope to see you then.