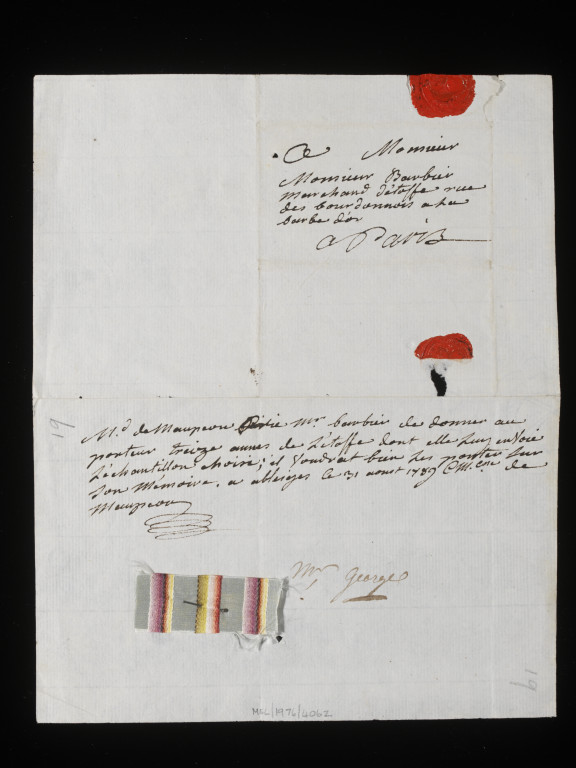

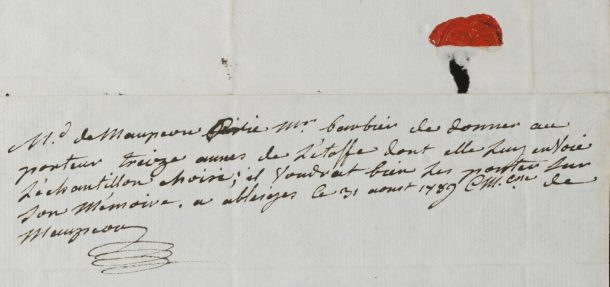

Mde de Maupeou prays Mr Barbier to give the courier thirteen aunes of cloth following the selected sample; he would also like to put them on his bill.

Ableiges 31 August 1789 Mde de Maupeau

The Europe Galleries will boast a display dedicated to ‘Silks’. Considering the progression of 18th-century silk fashions ‘from design to garment’, the display will show the design process from paper textile design to textile sample, and from lengths of silk to garments made up in silk. It will also illustrate a variety of fashionable silks, with woven and embroidered patterns, that would have been used for men’s and women’s dress.

Whilst greatly admiring the eye-catching 18th century silks that will feature in the display, it is a brief handwritten missive that provokes a more personal response in me. An ephemeral, day-to-day object, it provides a simple reminder of the human efforts, realities and individuals involved in the retailing of fabric in the 18th century. I feel it tantalising suggests a ‘more direct’ or personal connection with people of the past, in a similar way to Jacob Arend’s letter hidden in the Würzburg writing cabinet.

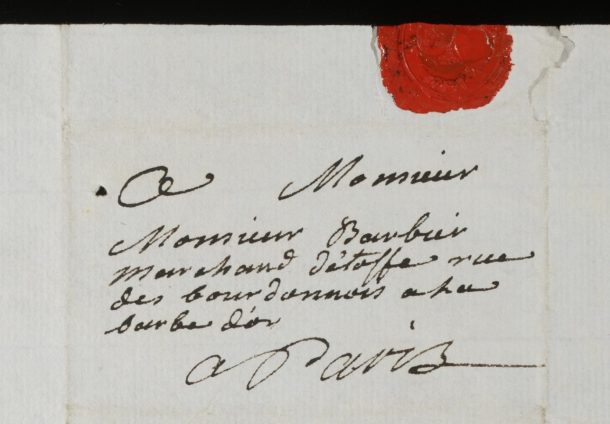

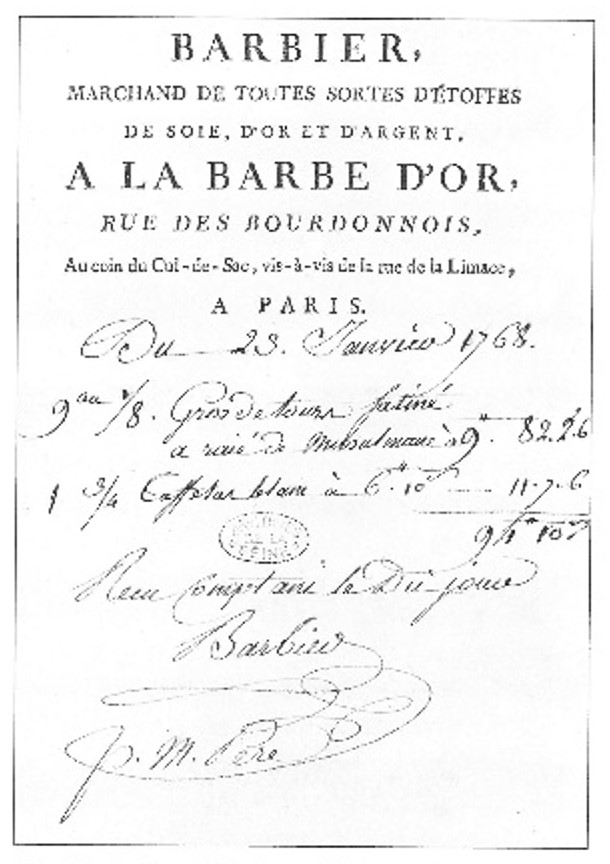

The letter is addressed to M. Barbier, who ran a family business retailing luxury textiles from the rue des bourdonnois in Paris during the second half of the 18th century and into the early 19th century. Its brief and to-the-point message (just over four lines in total) requests that lengths of a specific silk design be given to the courier who has brought the message [see my translation above].

The sender is Mde de Maupeou, who is writing from Ableiges, a commune in the Val-d’Oise department in northern France. The House of Maupeau was a French noble family. The name was made famous by René-Charles and his son René-Nicolas, both of whom were keepers of the Seals and lord chancellor of France during the reign of Louis XV .

Mde de Maupeou requests thirteen ‘aunes’ of cloth – the ‘aune’ or ‘aulne’ was a unit of measurement used for lengths of fabric. Its exact length varied throughout Europe in the 18th century, however by the late-18th century it was equivalent to about 46 ½ English inches. This means that Mde de Maupeou was requesting just over 15.35 metres. Mary Schoeser Boyce has posited that to produce a woman’s gown would require between 10 and 15 ‘aunes’, which suggests that Mde de Maupeou’s order was likely for such a purpose.

A sample swatch (echantillon) was attached to the letter to illustrate exactly which silk design Mde de Maupeou desired.

In the 18th century, fashion was expressed more through fabric, colour and pattern rather than through its cut. The most expensive material used was silk, which was woven into plain and patterned textiles. The main European centre of silk production was Lyon, in the south of France. Its designers supplied manufacturers with new patterns every season, which travelling salesmen and retailers sold across Europe. Having obtained their desired silk, customers would then usually employ a tailor or dressmaker to have their garments made to measure. In accordance with this, Barbier supplied textiles not only to customers who came to his shop in Paris but also clients (such as Mde de Maupeou) who requested items long distance.

Mde de Maupeou’s request is just one of around 486 letters and orders addressed to M. Barbier and his partner Tétard between ca. 1755 and ca. 1795, which are held in the National Art Library’s Special Collections (reference number MSL/1976/4062). The assortment of correspondence includes orders for silks, tafettas and other materials, mainly for clothing. In some cases, such as here, original samples of fabric are enclosed. Looking through the collection, Mme de Maupeou is found to be a repeat customer, as another letter records her ordering some striped ‘petit taffetas’.

Letters are addressed to at least two Barbiers (father and son), silk merchants specialising in woven silks whose business operated ‘à la Barbe d’or, rue des Bourdonnois’ for at least 68 years (1755-1823). Jean Nicolas Barbier (1750-1823) was the son of Jean François Barbier. Little is known of Jean François and due to our letter being dated 1789 it was presumably addressed to Jean Nicolas.

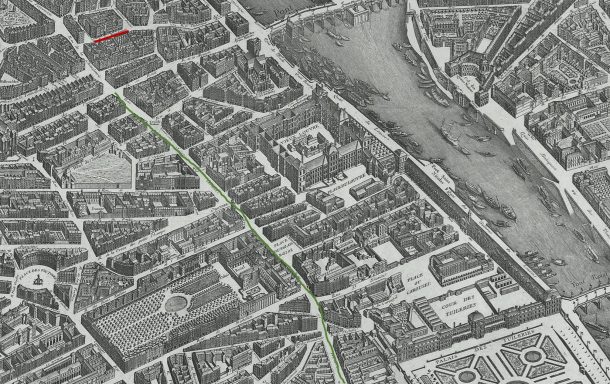

During the 18th century the rue St Honoré and the surrounding area came to be occupied by some of Paris’ wealthiest and highly regarded mercers and be renowned for the luxury goods on offer. Barbier’s shop on the rue des Bourdonnois was just 900 meters from the end of rue St Honoré, (if Google maps are to be trusted) it is just an 11 minute walk between the two.

Barbier had an extremely respected reputation, evidenced by the letters and orders received from members of the French aristocracy and from other customers, some outside France. Notably, he served as silk merchant to the French royal family (marchand de soie de la famille royale), between 1760 and the French Revolution. Orders were received from the Princess Lamballe (a favourite of Marie Antoinette), the Baron de Batz, Mme Campan (Marie Antoinette’s lady-in-waiting) and members of the court at Versailles.

[NB: I was interested to see that in ‘The Dauphin (Louis XVII): The Riddle of the Temple’ (1921) G. Lenôtre mentions an account for 1961 livres 17 sol for ‘silk materials supplied to the Temple by Barbier and Tetard, Rue des Bourdonnais’, connected to when the royal family were held there.]

Carolyn Sargentson’s ‘Merchant and Luxury Markets’ (1996) describes how Barbier was supplied by over eighty Lyonnais merchants. Despite being supplier to the King and having over two-hundred high-ranking clients, in 1762 severe cashflow problems brought Barbier into bankruptcy, with his debts and assets each calculated as totaling over four million livres. His stock alone was valued at over one million livres!

Barbier’s extensive business was recognised as being of great importance to the Lyonnais silk producers and a number of other enterprises that relied on it. The king therefore intervened and, with the Lyonnais, set up a syndicate to support and ensure the continuation of the business. This endeavour proved successful, as Mde de Maupeou’s letter testifies.

Mary Schoeser Boyce’s article ‘The Barbier Manuscripts’ (1981) takes a broader look at the contents of the collection in the National Art Library. She highlights a variety of interesting details which help to give an insight into some aspects of a silk mercer’s trade in 18th century Paris. Collectively, the letters have what Schoeser Boyce terms ‘great charm of unobserved conversation’. They include tantalising glimpses of daily human drama, such as a possibly mislaid key (alluded to in a postscript to a request for taffeta): ‘Monsieur Barbier is not able to give the taffeta which Mde de Tilly demands, for want of the key to open his shop.’

NB: If you have found this blog entry interesting, you may also like to read Lesley Miller’s ‘Selling Silks’ (2014). This publication demonstrates the important role of sample books in the selling of silks. It focuses on a merchant’s sample book in the V&A collections, which contains hundreds of silk samples and is believed to have been confiscated by British Customs in 1764. As well as faithfully reproducing the whole album, it provides a record of the 18th-century French and English silk industries and their commercial practices.