The Gilbert Collection is one of the most important collections of decorative arts in the world. It consists of 1,000 dazzling items of gold and silver, snuffboxes, portrait miniatures, pietre dure and micro mosaics. Stunning as they are, some of these beautiful objects conceal a troubling history. As part of the V&A’s commitment to proactive research into the history of ownership – or provenance – of the items in its care, a special display, Concealed Histories, tells the story of eight Jewish collectors and their families under the Nazis. It is the first of its kind by a UK museum.

Looted and restituted

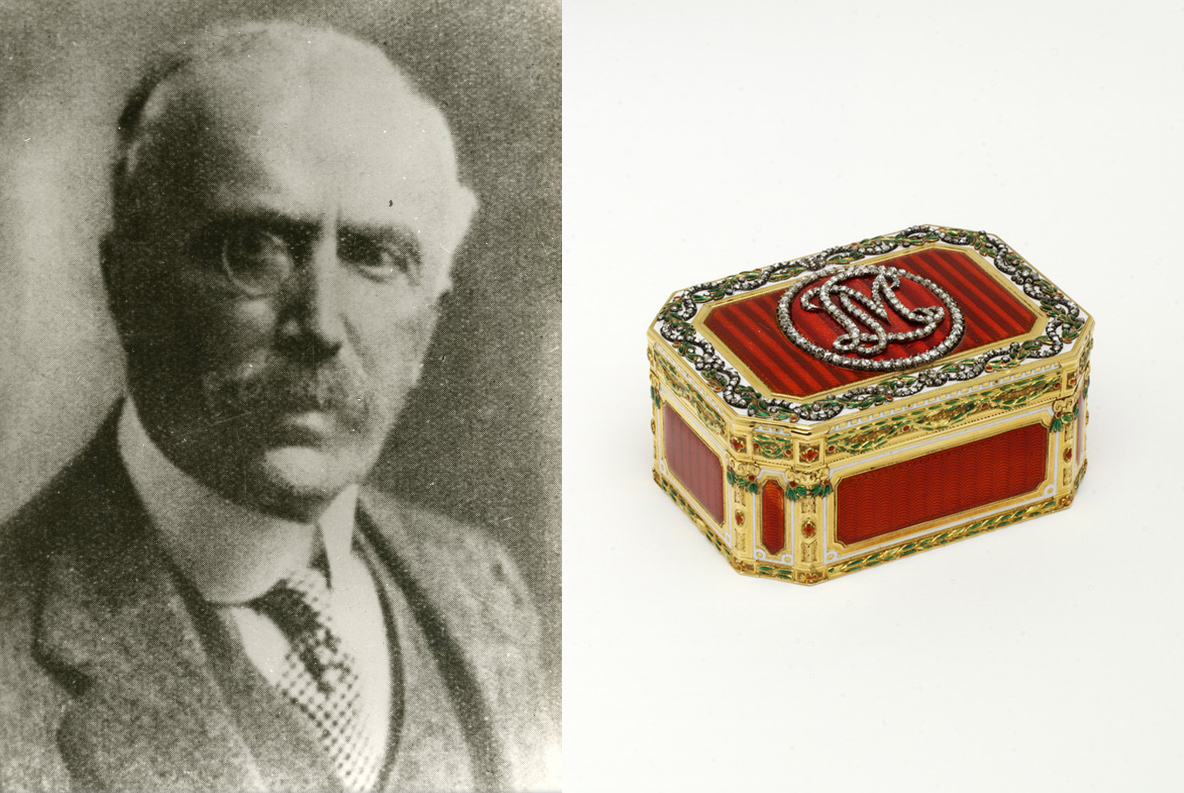

Some of the objects on display were looted by the Nazis but were restituted after the war. A striking example is that of a Louis XVI enamelled gold snuffbox with a diamond-set monogram ‘LM’, which once belonged to Maximilian von Goldschmidt-Rothschild (1843 – 1940). A successful banker who married into the Rothschild banking dynasty, Maximilian von Goldschmidt-Rothschild was one of the wealthiest individuals in the German Empire. In November 1938, the Nazi mayor of Frankfurt exploited the anti-Semitic violence engulfing the city and forced him to sell his entire art collection to Frankfurt’s museums. After the war Maximilian’s grandson, who served in the American military, demanded the restitution of the collection. We know that this snuffbox was returned to the family in 1949 through archival records kept by the Museum of Applied Arts and the City of Frankfurt.

Gaps in the provenance

While it was possible to establish a clear chain of ownership for Goldschmidt-Rothschild’s snuffbox, this is not always the case. Gaps in provenance are not unusual, particularly for the kinds of objects collected by the Gilberts. However, when those periods relate to the 1933 – 45 years of Nazi rule, and if we know that a given object previously belonged to a Jewish collector, these blind spots in an object’s biography are of course deeply troubling.

The Concealed Histories display puts objects on show in the hope that someone might be able to come forward with information that will help us fill this crucial history. A striking example is that of a colourful Johann Christian Neuber snuffbox, decorated with numerous hardstones, which once belonged to Eugen Gutmann (1840 – 1925), the founder of the Dresdner Bank. His wealth enabled him to build a collection of gold and silver treasures, which, according to a catalogue from 1912, included this box. However, apart from this 1912 catalogue, there is no trace of the snuffbox until it reappeared on the art market in 1983. This long gap is concerning: after Eugen Gutmann’s death in 1925, the bulk of his collection went to his son, Friedrich (1886 – 1944) in the Netherlands. After the German invasion in 1940, Nazi art dealers descended on the Gutmanns’ home. In 1942, they compelled Friedrich to send his father’s collection to Munich. In 1943, Friedrich and his wife Louise (1892 – 1944) were deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto, and were later murdered.

Why conduct provenance research?

This pioneering special display provides insight into the ongoing research into the provenance of the Gilbert Collection. This research is necessary because in many cases it is unclear who owned these pieces before they were acquired by Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert. This uncertainty can be alarming: between 1933 and 1945 Jewish people in Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe had their possessions systematically taken from them. Art collections were confiscated, sold, scattered or destroyed by the Nazis. Despite significant efforts after the Second World War by the Allies and European governments, many of these objects were never returned to their rightful owners. Instead, many objects ended up in public and private collections, often acquired without knowledge of their background, or whose hands they had passed through.

As children of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert were acutely aware of Nazi crimes. But, like many other collectors, they did not ask in-depth questions about the provenance of these masterpieces. It was only in the late 1990s that the art world began to address this dark legacy following the Washington Conference, at which 44 nations pledged to find ‘just and fair solutions for artworks still not returned to victims of the Nazis’.

How do you research something that doesn’t want to be found?

When the Gilberts acquired these masterpieces, the art market was booming, turnover was high, and sellers usually only provided information about illustrious royal or aristocratic provenance, as this would dramatically increase an object’s value. Gaps in the history of ownership were not seen as cause for concern.

Today we seek to discover more. We look to alternative sources, like the catalogues commissioned by the original collectors, or auction records where the auctioneer scribbled the name of the buyer into the margins. We also examine documents compiled by Nazis officials, such as inventories compiled by Jewish collectors.

Documents hidden in the archives in Germany, Eastern Europe, the USA and the UK often hold crucial evidence. But, in many cases, the provenance of objects taken by the Nazis cannot be traced because the relevant information was destroyed during the Second World War. This special display showcases our ongoing research into the provenance of the Gilbert Collection, and the complicated paths we have to tread in search of the answers.

Provenance research at the V&A

During the Second World War and its aftermath, V&A curators were actively involved in the recovery and restitution of Nazi-looted art. Before he became the V&A’s silver specialist in 1946, John Hayward was a member of a unit known as the ‘Monuments Men’, established by the Allies to protect and rescue artworks seized by the Nazis. Hayward was responsible for coordinating the return of Jewish libraries confiscated by the Nazis for the Hohe Schule, their centre for ideological research and education.

In the 1990s, Britain’s museums became aware that the Nazis’ widespread looting of art across Europe had left traces even in the UK. In 1996, the V&A received the only known complete copy of the inventory of the so-called ‘degenerate art’ confiscated by the Nazis from German public collections. Visitors will be able to explore this important document via a digital terminal and on our website as part of Concealed Histories. From 1998 onwards, the V&A was a driving force behind the efforts of UK museums to systematically research their collections in order to identify pieces which had been looted by the Nazis and were not restituted after the war. In 2018, it became the first art museum in the UK to appoint a Provenance Curator, dedicated to the Gilbert Collection. In addition to conducting proactive provenance research, the V&A is committed to sharing what it finds with a broad audience. Our goal here is to give our visitors from all over the world the opportunity to learn more about the darkest chapter in European history and, at the same time, to widen our appeal for further information on these objects.

Concealed Histories: Uncovering the Story of Nazi Looting, runs at the V&A South Kensington, Friday, 6 December 2019 – Sunday, 10 January 2021. Admission is free.

Curated by Dr Jacques Schuhmacher (Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Provenance and Spoliation Curator) and Alice Minter (Curator, The Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection). Email: j.schuhmacher [at] vam.ac.uk