One of the greatest things about working in the V&A, the world’s leading museum of art and design, is the opportunity to care for its amazing objects. The renovation of the newly named Ruddock Family Cast Court has allowed me to work on a remarkable collection of plaster casts of early medieval carved stone Christian monuments . While cleaning and conserving the them, I have been able to pick up fascinating information about their history, construction, condition and previous restoration treatments.

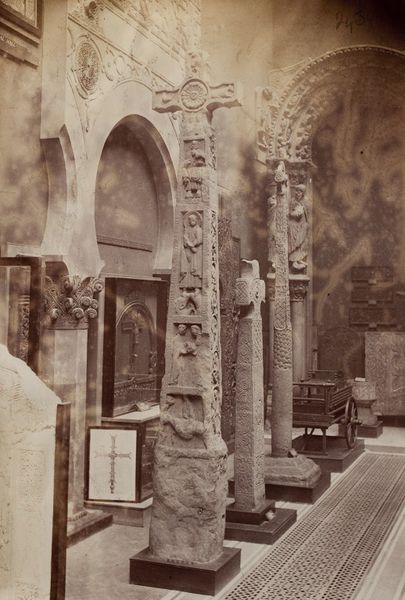

The crosses are arranged in the gallery between the bottom half of the colossal copy of a Trajan column from Rome, which is displayed in two halves due to its 35-metre height, and a 17-metre-wide cast of a the Pórtico de la Gloria, a 12th-century façade of the cathedral at Santiago de Compostela. The crosses rise from their plinths, reaching for the light as if they were trees, creating an avenue between the gigantic architectural casts from Rome and Santiago.

The original crosses, which date from the 7th century onwards, are scattered in various churches and Church yards across the British Isles. The Museum acquired the plaster copies between the 1880’s and the 1920’s.

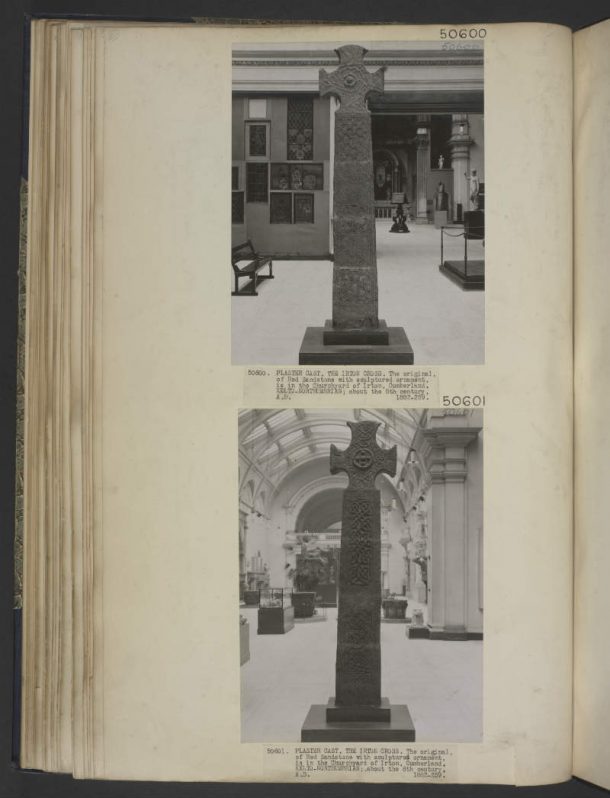

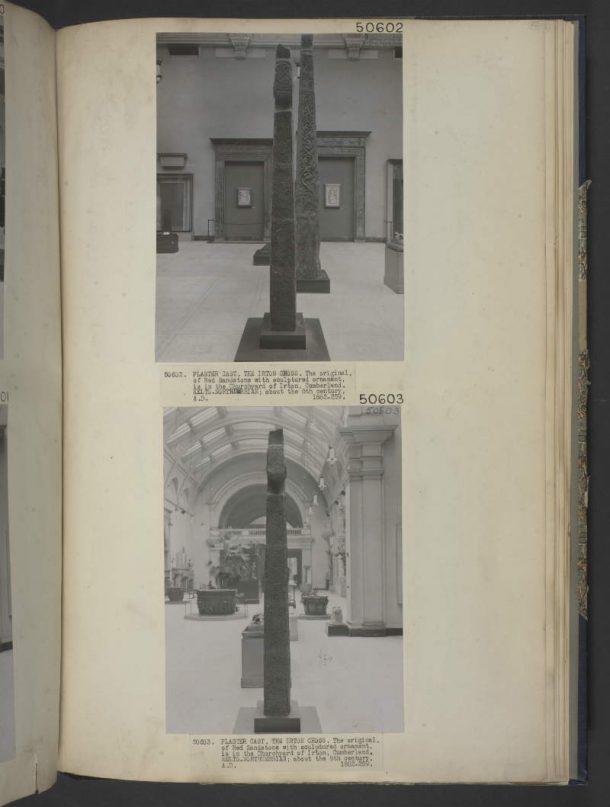

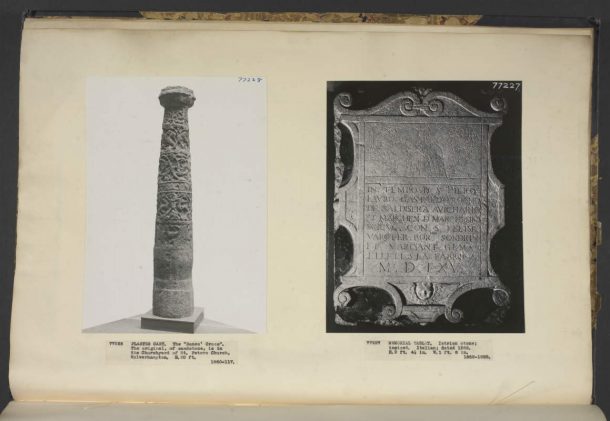

The Museum’s archival collection of Guard Books contain photographs of the crosses previously displayed in the galleries which now house the Museum’s collection of Medieval and Renaissance art.

Each cross has their own individual characteristics, colour and form. They also differ in height and proportions, as some are quite broad and some are thinner.

The crosses were manufactured by various 19th century plaster modellers, although some of their makers are yet to be identified. Copies of the eighth-century Pictish cross-slab at Nigg, which is one of Scotland’s greatest art treasures, were manufactured by a London based Brucciani & Co. who also modelled a number of other objects for the V&A, including the 1866 Pórtico cast and sections of Michelangelo’ David, including his nose, left eye and lips, offered copies of the 8th-century cross-slab at Nigg for sale. However, the earliest complete Nigg casts, including the one in the V&A, were made by Edinburgh-based Joseph Cavagnari. The Ruthwell Cross was cast by an Edinburgh-based figure-maker, Leopoldo Arrighi (c.1834-1899) and the Wolverhampton, Irton and Gosforth Crosses were cast by a Royal Engineer, Sergeant Bullen, who worked in the Museum as a ‘Foreman Moulder’. The smaller Manx crosses which originate from the Isle of Man, were cast in 1866 by London-based Giovanni Franchi whose company manufactured electrotypes, copies in plaster and fictile ivories.

The plaster casts of the high crosses are all painted to resemble their original counterparts which are carved from various types of stones. Remarkably the surface of the casts shows the condition and texture of the original crosses when the moulds were taken. Some of them have also small traces of raised seamlines and other markings which have been left by various casting processes.

The crosses have undergone several restoration campaigns in the past but unfortunately none of the previous conservation records survive. However, I am looking forward to the results of the analysis of the samples taken from the crosses by the Museum’s scientists.

Most of the old repairs are relatively easy to spot as the materials to fill missing gaps have either disintegrated or are uneven, or the over paint to disguise the repairs is slightly different colour. Interestingly, most of the crosses have also been treated with mixtures of wax and other unidentified materials, probably to protect them and to make them easier to clean. The Muiredach’s High Cross is covered in a particularly thick coating of wax and on its top part I noticed a stain which could possibly be residue of a a casting material indicating that perhaps another mould was made from the V&A cast. Interestingly the sides of the Muiredach’s High Cross cast are better preserved than the front and back, as they tend to be less clogged up with dirt and over-paint.

While examining the crosses I noticed that many of them had suffered damage to their highest and lowest parts. The damage to the lowest parts is mostly abrasions and chipping caused by people touching (which shows how damaging this can be). The damage on the highest parts, where the painted surface has suffered from losses and flaking, is probably caused by a combination of exposure to sunlight and moisture. The old glass roof in the gallery used to leak but it has been now has been replaced with new glass.

All the crosses have been constructed from several sections and the joints are clearly visible. Many of the sections have uneven edges and the fills to cover the gaps were found to have either cracked or they were loose or they were missing sections. As part of the conservation treatment, I refilled missing gaps on joints, and retouched them to match the surrounding colours. Some of the joints were also found to be slightly misaligned which may be because the crosses were moved to a different locations within the Museum and the gallery space.

The Wolverhampton cross had a removable cover on its top, which has now been replaced, as the old cardboard cover had warped. Underneath, I discovered a supporting wooden channel and the plaster panels were attached to the it with metal pins. I tried to peer inside the Muiredach’s High Cross through a few millimeter gap on a joint at its very top and I am sure that I saw a similar wooden structure as I had seen inside the Wolverhampton Cross.

It wasn’t possible to take the crosses apart to examine their internal structure but even so I believe that they all have wooden structural supports on their insides. Many of the crosses have several nails and screws which have been attached through the plaster to an internal support.

The copy of the Pictish cross-slab from Nigg has a fascinating construction. The cross is made of sections containing thin layers of plaster supported with hessian and metal wire on the interior. Sadly, due to the way it was mounted in the past, the plaster panels have fractured. The iron screws which have been sunk in to the plaster through the wooden mount had corroded and expanded opening up a fine network of cracks. In addition to cracking, much of the crosses painted surface has also been damaged requiring extensive work to stabilise it.

The process of cleaning and examining the crosses has been exciting as I could closely monitor their condition, and at the same time, reveal their beautiful decorative details.

I took fairly subtle approach to cleaning. After dusting their surfaces with soft brushes under vacuum suction, I removed more stubborn dirt with either specialist dry- or wet-cleaning sponges. I felt that the patina on their surface was part of their history and charm. To clean the crosses and to reach their very tops I had to climb up and down various scaffold structures. Despite the crosses being structurally sound, I had to be extremely concentrated and gentle while I handled them as they swayed at the lightest touch. To treat abraded surfaces and areas of flaking paint, I applied small amounts of adhesive for stability. To finish the work, I retouched them with acrylic colours to match the surrounding colour schemes.

Conserving the crosses has been an exciting undertaking and I am honored to have been given the opportunity to care for such exquisite and wonderful objects. I also hope that visitors will be able to appreciate them in a new light. There are many interesting websites that provide fantastic information about the original crosses, for example, some of the crosses have also been replicated using 3D visualation techniques by the Centre for Advanced Irish Archaeological Research on their Discovery Project.

I’m grateful to Allchurches Trust for their generous funding towards the conservation work. I’m also grateful for my colleagues Mariam Sonntag and Chloe Stewart who supported me in the final stages of the conservation work. I would also like to thank Nicholas Smith in the V&A Archives, Valentina Risdonne, Dr. Lucia Burgio, Charlotte Hubbard and Dr Sally M Foster.

Stay tuned for the next blog in the series: ‘Scottish agency in the V&A Cast Court Collection’ by Dr Sally M Foster.

Johanna, thank you for your interresting article. I am sculpture conservator too and I am interrested in materials you use for conservtion of plaster casts. Can you give me some details (what materiál did you use for fillings) or recomend me some article where you or your colleague wrote and where the used materials are desribed? Thank you Jakub

Dear Jakub, thanks for your comment. I used many different types of materials depending on the area I was working on. You can read more about the casts and their treatments on the V&A blog and on the following publications: Víctor Hugo López Borges, Johanna Puisto: The conservation of the Cast Courts at the Victoria and Albert Museum. The Cast of the Pórtico de la Gloria. Copia e invencion: modelos, réplicas, series y citas en la escultura europea, pages. 227-242, Museo Nacional de Escultura (2013).

Angus Patterson, Marjorie Trusted: The Cast Courts, V&A Publishing (2018).

Best wishes,

Johanna Puisto