One day while I was searching the V&A’s collections database of Michelangelo’s art, I stumbled upon a peculiar item – a solitary plaster nose from the statue of ‘David’. Since I’d had first-hand experience in cleaning and examining the nose of the Museum’s full-scale replica of David (which still has a nose!), I wondered who created the copy and for what purpose? Was the mould for the copy taken directly from the face of the full-scale figure and what was the copy doing hidden away in our store?

Unable to find an image of the mysterious object I managed to track down its location. To my amazement, I was soon sent out to the very same store where the nose was kept to assess a group of tombstones. At the store, I convinced my colleagues to help me find the nose and after a brief search, it was uncovered in a crate with other small plaster objects, tucked in beside a cast of an Egyptian King. Excited by the discovery we decided to take the nose back to the Museum, wrapped it carefully in tissue paper, and drove it back to South Kensington.

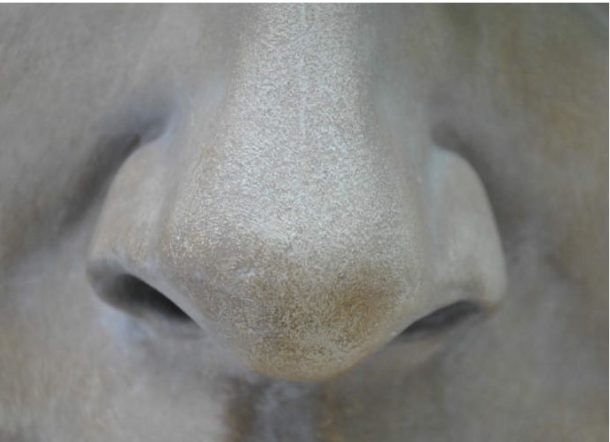

Back at the lab, I unwrapped the nose and examined it. Interestingly it had faint raised seamlines, typically left by the casting process, which are also noticeable on the full-scale David. The surface was covered in years of ingrained dirt and it looked as if it had never been cleaned. Sadly, it had suffered from abrasions and chipping but despite its flaws it was structurally stable and looked remarkably poised.

As I stood there examining the nose, I remembered a surreal story from 1836 by Nikolai Gogol. The story goes that a nose belonging to a St Petersburg official, found inside a loaf of bread, ends up as a high-ranking officer and starts roaming around the streets of St Petersburg wearing a uniform. Below is a clip of Shostakovich’s adaptation of Gogol’s satire which was shown at the Royal Opera House in 2016.

The nose was inscribed by Domenico Brucciani & Co, London and dated in 1891. The base was inscribed with a mysterious code 2250 A, which later turned out to be its catalogue number. It was marked as the second copy out of six and I wondered why the company had only produced such a small number of casts. Could they be prototypes for a mass production or a special edition?

Brucciani & Co. were a renowned London-based Italian family of plaster modellers. Domenico Brucciani (1815-1880) ran a lucrative business from his company’s headquarters in Covent Garden. He produced plaster copies of objects held in the collections of museums such as the V&A, British Museum, the National Gallery and Natural History Museum. In 1891 D. Brucciani & Co was run by plaster modeller Joseph L. Caproni (1846-1900). Thus it is possible that the nose was used as a teaching material at the National Art Training School in the Department of Science and Art at the V&A.

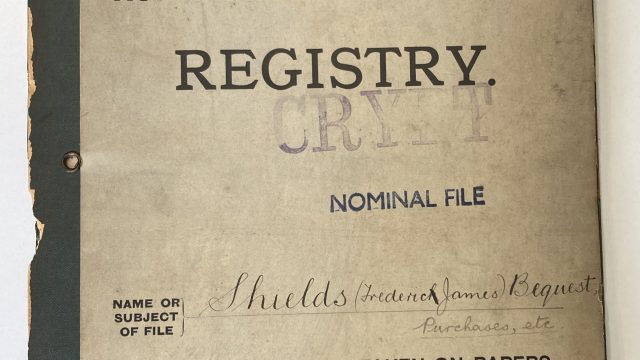

The V&A still has several of Brucciani’s plaster casts, such as David’s famous fig leaf (although unsigned) and the full-scale replica of ‘Portico de la Gloria’, a 12th-century façade at the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. The Board of Education took over Brucciani’s business after the company was placed in voluntary liquidation on 8th April 1921. The V&A ran an on-site casting service until 1951, when the business was closed. Keen to learn more about the location of the casting service, Brucciani’s business and the nose, I decided to pay a visit to the V&A Archives.

At the archives I looked through mountains of documentation about Brucciani, but unfortunately there was no mention of the nose. However, after going through pages after pages of memos about the process of handing over the business, I came across a 1933 ground plan of the Museum’s Cast Department. It was three stories high, with workshops on the first floor, sales rooms, offices and the drying room on the ground floor, and cast stores in the basement. It was located at the back of the museum, which today houses conservation studios and mount makers’ workshops.

Back to the nose. Whilst contemplating what to do with it I was introduced to George Eksts, an artist and a photographer from the Word and Image Department, who was keen to create 3D images of objects in the Museum’s collections. I invited him to take images of the nose, which were then formatted in software that creates 3D images in the form of photogrammetries. This means that the nose is now well documented for when we put it back in store.

Unable to get the nose out of my head, I thought what to do next. I’d heard that the British Museum had sold copies of David’s nose in their shop and I wondered whether I should contact them in case they knew something about Brucciani’s original mould. By chance, I was contacted by Martin Declève, a photographer from Brussels, requesting to photograph historic piece-moulds representing characters of the antique Greece and Rome. Since the V&A had no piece-moulds in the collection, I wrote to the British Museum to find out if he could photograph their moulds. I also took the opportunity to ask if by any chance they had the mould for the nose, and surprisingly I was told that the BM did indeed have it and it corresponded to the catalogue number 2250A.

George also made this sequence of the nose mould. Video George Eksts, courtesy of the Trustees of British Museum.

https://vimeo.com/194971343/cad843b605

They also had moulds of David’s other facial features such as his eyes, lips and ears, which George and I arranged to visit and photograph.

I also managed to trace the casts for David’s left eye and lips in the V&A collection, and I arranged for these to be photographed as well.

The British Museum put me in touch with their facsimile specialist Michael Nielson, who creates facsimiles from the museum’s collection, and has a special interest in Brucciani. Michael invited me for a chat about Brucciani and the nose, and he told me an interesting story about Brucciani’s association with the British Museum. This story and more information about David’s nose will be included in a new series of posts coming to the V&A blog very soon!

In the next post, Dr. Rebecca Wade, Assistant Curator (Sculpture) from Leeds Museums and Galleries/Henry Moore Institute will describe how David’s nose was used for art education. Stay tuned for Follow your nose: Brucciani’s plaster casts of the face of Michelangelo’s David as object lessons for art education.

Acknowledgements:

I would like to extend my sincerest thanks and appreciation to Anthony Spence, Angela Rawbottom and Michael Neilson from British Museum for giving me access to study and photograph their collection of moulds. I would also like to thank George Eksts for photographing the moulds and the casts and formatting them to 3D, and special thanks to Miranda Wesson, Rebecca Knott and Sherrie Eatman for helping to edit my text.

Did you know you could touch the scan of the nose using haptic technology. ……I have been working for the past 5 years creating Gallezeum which is a unique interactive console we will be launching at INNOVATE UK at the NEC Birmingham 8-9th November. We have trialed the system at Manchester Museum and recently won a Jodi Award Commendation for accessible digital Culture. We are a small company based in Stoke On Trent http://www.gallezeum.org more inclusive digital access to collections like the classic object you have found

The cast of David was made up of dozens of small cast elements. The wooden-framed moulds for these were thrown out by the V&A many decades ago. Sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi found them in a skip and reclaimed many of the smaller ones to use himself. As a result I (and many others I suspect) have a cast of David’s nose by Eduardo from the original mould.

Are the casts still available? I have the nose and mouth and would now like the eye and ear. Thanks. Jy

When I visited the British Museum in the late 90s, four of the plaster casts were available for sale in their store. I purchased them with the intent of giving all to my eye/ear/nose/throat doctor for his new office. Unfortunately he died before I could present them. I still have them sitting on a mantel.

From Josep:

We’ve in our instituion some classical plaster casts.

Actually we’re requesting information concerning to our ( size scale 1/1 )

Phidias’s Illisos plaster cast.

Thanks to your article, not discard the Brucciani’s authority or some later successors.

Joanna do you know any other british cast makers from after the ’50s ?

Thank you¡