We are all familiar with the important collections of fine and historic photography held by the V&A and other institutions. But in many ways those are merely the tip of the Museum’s very large photographic iceberg.

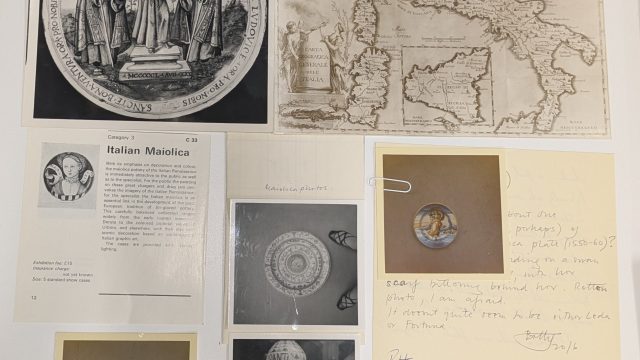

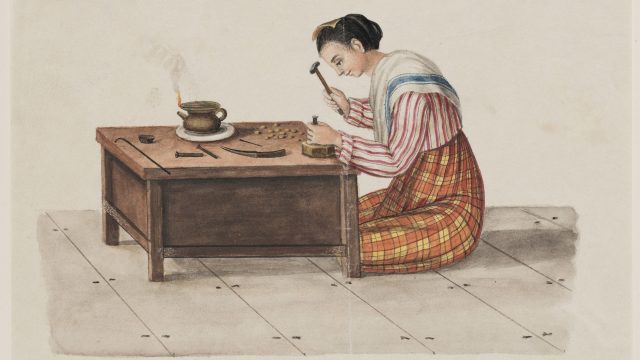

During my time as Andrew W. Mellon visiting professor, I have been thinking about the cultures of photography across the V&A. These different processes and outcomes reveal its history, and inform its present and future. Museums are saturated with photographs and photographic practices as they record and make their object collections available. One could argue that photographs have been the mortar that holds together the very practice of museums for at least a century. In effect, in some sense museum objects become a sum of the photographs taken of them: inscribed in accession and collections management; ‘contextual’ photographs (tucked into related documents files perhaps), conservation photographs, loan and condition reports, gallery prints, marketing and sales, publications, all sprawling over structures of curatorial practice – museum collection, archive, library.

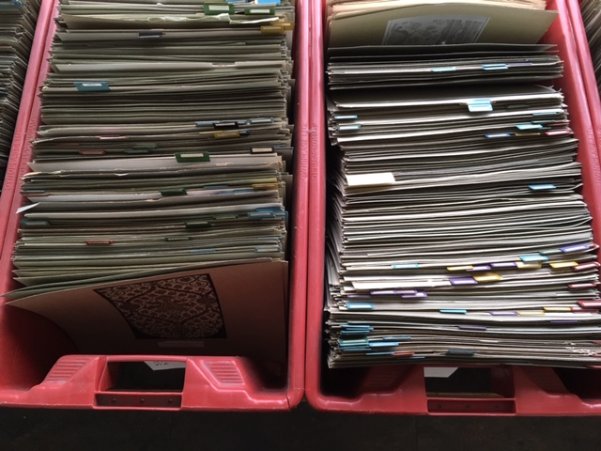

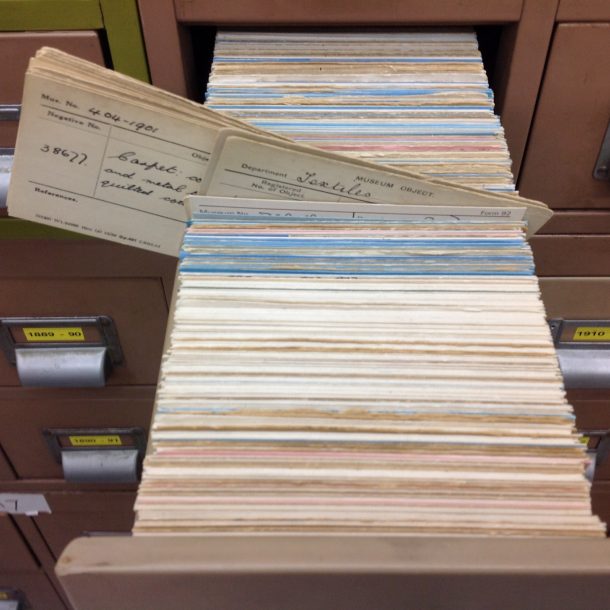

Such photographs also exist in multiple material forms, all of which have discrete material, functional and historical identities – negatives, prints, digital files, lantern slides, 35mm transparencies, publication prints, copies of copies, copies of copies of copies, a vast network of dependencies, all of which are historically located. The apotheosis is perhaps the museum shop, where ‘collections’ of objects are reduced to a series of consumable printed photographs, and spread across innumerable forms.

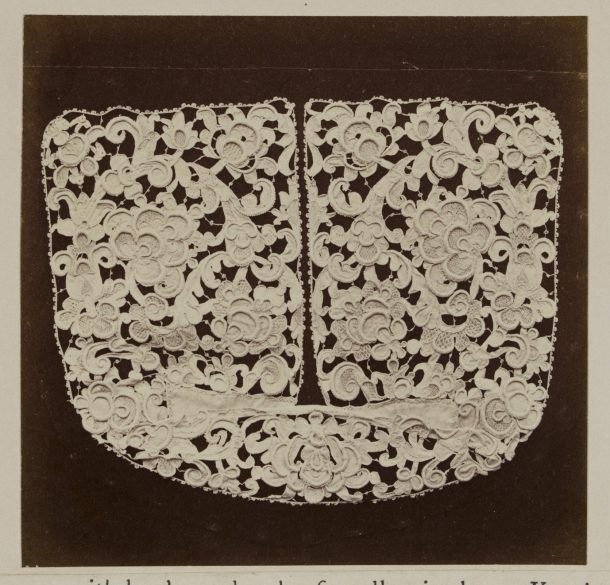

We can describe these as ‘non-collections’ – that is, they are present in the institution in huge numbers but are not accessioned or recognised as part of ‘the collection’, yet they have profound impacts and are deeply embedded into museum history. Significantly, in the mid-nineteenth century, albums and portfolios of mounted photographs of objects, whether in actual museums or not, and be they arms and armour, ceramics or paintings, themselves became known as ‘museums’. This is interesting because it reveals a long and continuing tradition of museums being made up of photographs and photographs making up museums.

The all-saturating and all-supporting work of photographs in a museum might be seen as an ecosystem. An ecosystem is, as we all know, a barely perceptible yet palpably present network of finely balanced, yet vital, sets of interconnections, dependencies, benefits and threats. It sustains a particular environment expressed through, in our context here, practices, materialities, hierarchies and values. This ecosystem demonstrates exactly what photographs are ‘doing’ in the Museum.

These connections are crucial to museums because photographs constantly suggest both the existence and experience of objects. How often in daily practice are photographs of objects looked rather than the object itself, as if those photographs were the object itself, in a continual slippage between object and record? Even ‘collected’ photographs themselves are subject to such practices –copy negatives are made, file prints gathered, and postcards produced. This raises questions about which photographs a museum treats as ‘important’. On one register, all such photographs are important because they are not simply ‘of objects’. Rather they embed the history, values, structures and hierarchies that formulate ‘museum collections’ – they reveal what the museum is ‘doing’.

This prompts questions about what informs these structures and hierarchies.

What is the interplay between ‘collections’, and ‘non-collections’, the invisible photographic practices that shape those structures and hierarchies? What kinds of photographs are deemed to have curatorial ’identity’ in their own right, and what are merely gathered as an accrual around other classes of object? What is curated, what survives through benign neglect and what is disposed of? What remains submerged? How do photographs change category over time and under what conditions? ‘Non-collections’ photographs, in fact, vastly out-number those seen as ‘important’ under one rubric or another. However, the presence of the former is often hardly acknowledged as they too often remain, uncatalogued, in ‘service’ corners of museums. What might we learn from an expanded concept of ‘significant photographs’ in the museum?

We have now started to think about its photographic activities in this expanded way. The acquisition of the Royal Photographic Society collection provided a major impetus because it brought different kinds of photographic object into the museum, and so highlighted our own photographic practices.

The glories of the National Collection of Photography at the V&A remain, but among the objects in the new Photography Centre are new forms of treasure. Such photographs are testimony to the depth and breadth of the Museum’s relationship with photography, such as photographs taken by the Museum’s first female studio photographer. It is a relationship that can not, I think, only be expressed through the collections of fine art photography, but through an understanding of the whole ecosystem of often-invisible photography that allows the institution to be what it is.