An outstanding example of architectural woodwork displayed at the Legion of Honor, part of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, is a painted and gilded wooden ceiling, or artesonado, from the lost palace in Torrijos, near Toledo, Spain. One of four such ceilings in the four towers of the palace, it was built in around 1490 for Gutierre de Cárdenas, Lord of Maqueda (about 1440 – 1503), a prominent advisor to Isabella I of Castile, and his wife, Teresa Enríquez de Alvarado (about 1450 – 1529). Following the demolition of the palace at the turn of the twentieth century, the ceilings were sold and dispersed. You can read further details in one of the earlier posts in this series. The ceiling currently in San Francisco embarked on an odyssey spanning four decades, arriving at last in a corner of the world that, though an ocean and a continent away from Torrijos, fittingly has a strong Spanish colonial legacy.

Artesonados are elaborate, geometric wooden ceilings consisting of multiple interconnected, richly painted and gilded beams and panels. They adorn such notable structures as the Alhambra in Granada and the Aljafería in Zaragoza, and became a component of the so-called Mudéjar style of architecture. They often combine Christian and Islamic design elements, fusing or synthesising two of the cultures that inhabited the Iberian Peninsula in the medieval period.

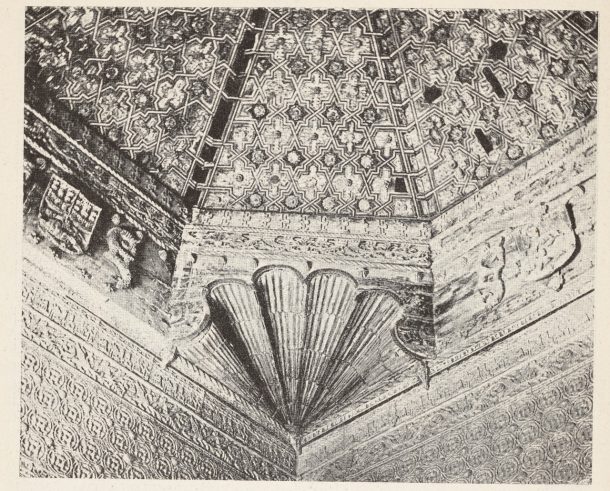

The artesonado at the Legion of Honor spans 5.5 metres (18 feet) across and consists of 17 panels. A central octagonal panel is bordered by eight trapezoidal panels to form an octagonal dome. These are in turn framed by four rectangular wall panels and four corner squinches carved like scallop shells. The nine dome panels are decorated with Islamic latticework patterns, while the middle of the central panel features a carved muqarnas boss.

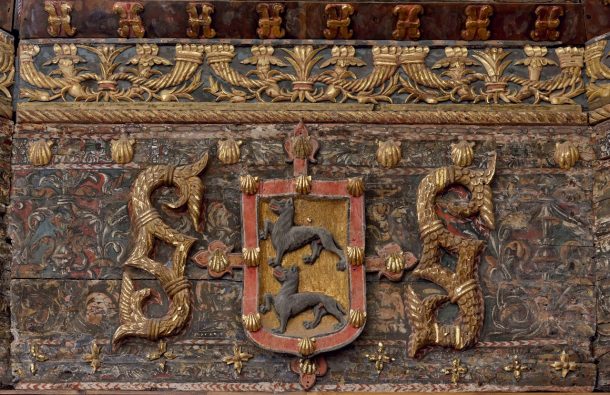

The border panels, by contrast, display the distinctly European coats of arms of Doña Teresa (gilded crenellated castles on a red field and a gilded lion on a white field shaped like a teardrop) and of Don Gutierre (two black mastiffs on a gilded field encircled by gilded scallop shells).

The scallop shell motif, repeated on a far larger scale in the four corner squinches, symbolised Christian piety during the fifteenth century, its radiating lines recalling the convergence of pilgrimage routes at Santiago de Compostela, the shrine of Saint James the Great. The patron saint of Spain, James was one of the twelve apostles of Christ. He allegedly had a vision of the Virgin Mary while preaching at Compostela in the northwest of present-day Spain and his remains were interred there. He was also known as James Matamoros (‘Moor slayer’), due to his legendary appearance during the ninth century to lead an outnumbered Spanish Christian army to victory in battle against the Arabs (the ‘Moors’), some 800 years after his death. Santiago de Compostela had special significance to Gutierre de Cárdenas because he was also chief commander of the military order of Santiago. The scallop shells thus complement his coat-of-arms and serve as a reminder that, despite the synthesis of Gothic and Islamic elements in the palace’s decoration, it was constructed at the same time as the Spanish Christians’ victory over the Muslim Nasrid sultanate of Granada in 1492.

When the palace was demolished, the four tower ceilings were dismantled and sold. The Legion of Honor ceiling was purchased by an American businessman named Charles Deering (1852 – 1927).

Born in South Paris, Maine, he was the son of William Deering (1826 – 1913), who co-founded International Harvester, a manufacturer of agricultural machinery. Charles Deering was an officer in the United States Navy from 1873 to 1881, when he resigned to assume leadership of his family company. During his naval postings overseas, he travelled widely in Europe and Asia and developed a keen interest in the arts. His artist friends included John Singer Sargent (1856 – 1925), the Swedish painter Anders Zoorn (1860 – 1920), with whom he studied in Paris in 1893, and the Catalan artist Ramón Casas i Carbo (1866 – 1932), who painted the above portrait in 1914.

Charles Deering was particularly enamoured of Spanish art. In 1910, the year of his retirement, he acquired an old hospital building in the town of Sitges, just south of Barcelona. With the help of Spanish designer Miguel Utrillo (1862 – 1934), the building was refashioned into a palace museum, the Palau Maricel, incorporating various Spanish architectural styles and fragments. The palace survives today as a civic cultural venue used by the town of Sitges for concerts and events.

The Torrijos ceiling was installed in the palace’s chapel. The north and south walls were decorated with Mudéjar plasterwork. In these walls were set two baroque altars. Above was a frieze decorated with Arabic calligraphy and above this was a frieze decorated with shells. Similar friezes are mentioned in a description of one of the four tower rooms in the Torrijos Palace in Miguel Antonio Alarcón’s 1893 biography of Teresa Enríquez, and there are Arabic inscriptions in the plasterwork accompanying the Torrijos ceiling now in the V&A. This suggests that Deering and Utrillo may have intentionally recreated aspects of the original tower room in the chapel at Sitges to display the ceiling. Today, an octagonal canopy denotes where the ceiling was once situated.

Charles Deering hoped that the Palau Maricel would be a centre for artists to work and study, as well as a repository for his extensive collection of Spanish art. This included paintings by Zurbarán, Goya, Rusiñol, and others, as well as Gothic sculptures and antique furniture from Castile, France, and Flanders. In 1921, however, he abandoned this plan and the Palau Maricel altogether and relocated to Chicago, taking his collection with him. Following Deering’s death in 1927, much of his collection was given to the Art Institute of Chicago. However, at the suggestion of the Art Institute’s director, Deering’s daughters gave the ceiling to the De Young Museum in San Francisco in 1946. The ceiling panels had, apparently, remained packed in crates during their decades in Chicago.

Why the De Young was chosen remains unclear, as any correspondence between Charles Deering’s daughters and the museum has not been preserved. One possible reason is the strong Spanish legacy in California. Following the arrival of Spanish explorers led by Gaspar de Portolá in 1769, the Misión San Francisco de Asís, the first Catholic mission in what is now the city of San Francisco, was established in 1776. The adobe church is the oldest building in San Francisco today. In 1821, California became a territory of an independent Mexico, before it was acquired by the United States in 1847 during the Mexican-American War (1846 – 1848).

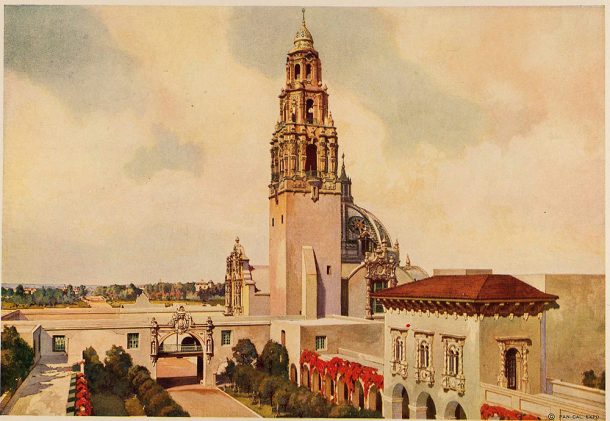

There was also, from around 1880-1940, a strong interest among Americans in Spanish Colonial Revival or Mediterranean Revival architecture, particularly in former Spanish colonial possessions like California and Florida. The popularity of these styles peaked in the 1920s and 1930s, following the Panama-California Exposition of 1915 – 17. This exposition was intended to showcase San Diego in Southern California as the first American port of call for ships sailing northward from the Panama Canal. Architect Bertram Goodhue (1869 – 1922) designed the pavilions in a novel revival style inspired by elaborate Spanish and Mexican Baroque architecture, as well as Spain’s Islamic architecture. Examples survive in San Diego’s Balboa Park, including a tower inspired in part by the Almohad (12th-century) minaret now known as La Giralda in Seville. Following the Exposition, Spanish Colonial Revival became the preferred historical style for administrative and residential buildings in California – to the present day.

While the Spanish Colonial Revival is more visible in Southern California, perhaps the most significant example in Northern California is La Cuesta Encantada or ‘the Enchanted Hill’ near San Simeon. Better known as Hearst Castle, it was designed by architect Julia Morgan (1872 – 1957) for the publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearst (1863 – 1951) and built from 1919 to 1947. Hearst was inspired by Goodhue’s designs for the Panama California Exposition and also had Morgan base her designs directly on Spanish examples, such as the Church of Santa María la Mayor near Málaga. The eventual result was a vast, sprawling complex with 115 rooms. In Hearst’s words, the castle was intended to be a ‘museum of the best things I can secure’, and numerous architectural fragments that Hearst had acquired in Europe – doorframes, chimneypieces, and panelling – were incorporated into the structure.

These also included some 30 artesonados from Spain. The ceilings of the castle’s morning room and of Hearst’s bedroom likely came from palaces in the Spanish city of Teruel. The ceilings were meticulously restored in 2020. Given California’s Spanish heritage, the popularity of the Mediterranean Revival styles, and a history of collecting Spanish architectural elements, it is perhaps fitting that one of the Torrijos ceilings ended up in that particular part of the world.

The ceiling was installed at the De Young Museum in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park from 1948 to 1989, when it was dismantled for extensive conservation. Hundreds of hours were spent cleaning the panels, removing poorly restored overpaint, and restoring the gilding. It was determined that the uppermost registers of the four wall panels, decorated with gilded H-forms, had been lost around the time of the 1948 installation. These were reproduced according to photographs in Spain’s National Archives. Finally, in 1995, the ceiling was installed at the Legion of Honor (the Legion of Honor and De Young having merged to form the Fine Arts Museums in 1972), where it complements a collection of early Renaissance paintings and sculpture and represents a key moment in the architectural history of Spain, as well as one of the chief influences on architecture in California.

Exceptional piece – thank you.

We might also note our fine dom Gutierre was also the Mayor of Toledo, and the first one in to the, after 700 years, liberated Alhambra Castle