Enamelling is the process of fusing finely-ground glass to metal. Painting portrait miniatures in enamel required immense skill – each colour of glass powder had to be carefully mixed into an oily medium before being applied to a metal sheet and fired in a kiln. Artists added enamel to the reverse of the metal sheets – known as counter enamel – to make sure the metal expanded evenly during the firing process. This prevented warping or cracking to the painted image on the front. As the reverse side would generally not be seen by anyone but the owner, counter enamel was often of lower quality, containing more impurities. The bluish tints on the reverse of many enamel portrait miniatures, for example in this portrait by Carl Christian Kanz, are caused by these impurities.

Given that the reverse of a miniature was generally hidden from view, many artists left the counter enamel blank. But some made the most of the extra painting surface by adding an inscription or design. Most often the space was used for signatures and dates. Viewing the Gilbert’s enamel miniatures from the back reveals just how common this practice was.

More and more frequently, enamel painters began to include longer inscriptions on the reverse, visible only to those with an intimate relationship to the object. For example, the inscription on the reverse of a miniature of Queen Charlotte references the full-length oil painting by Thomas Gainsborough that it was copied from.

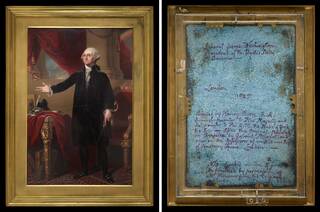

One of the largest miniatures in the collection, a portrait of George Washington, measuring 30 x 20 cm, has a particularly long inscription that reveals how it was made. The enameller Henry Bone (1775 – 1834) notes how the piece ‘Cracked in the 5th fire’ and was only finished with ‘the permission of Mr Williams’, his patron. Here, the crack was likely a result of not applying a dense enough layer of counter enamel needed to retain a high tension. The inscription illustrates how unpredictable enamelling could be even for experienced artists like Bone, who had successfully created his largest enamel painting (measuring 40.5 x 46 cm) a decade before this one.

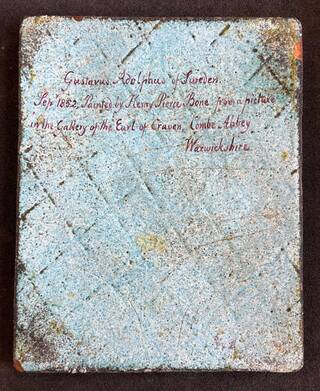

Bone and his son, Henry Pierce Bone (1779 – 1855), almost always included an inscription on the counter enamel of their pieces. The counter enamel on these two portrait miniatures was hidden for decades, but removing their frames has revealed the inscriptions.

The inscription on the reverse of the painting of Frederick Henry has survived in much better condition and is more legible, also showing evidence of tools used in the making process. Both were at some point removed from their original frames, leaving numerous chips to the enamel which makes the copper supports now partially visible.

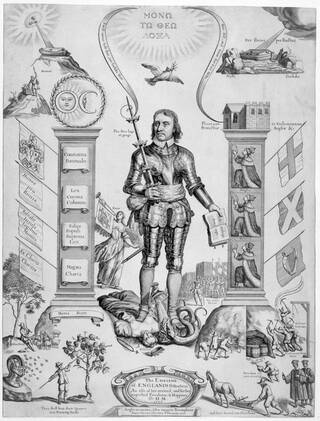

On very rare occasions, artists decorated the reverse of enamel miniatures with unique designs or patterns that would offer a commentary on the personality depicted on the front. For example, a miniature of Oliver Cromwell by Christian Richter (1678 – 1732) from about 1720, includes visual references to an engraving from 1658 known as The Emblem of England’s Distraction. Filled with allegorical symbolism, this reference to a renowned pro-Cromwell image may reveal something about the political views of the person who owned the miniature.

More often than not these secret messages have remained hidden from view, completely enclosed within a locket, gold box, or frame that would be just as decorative as the portrait itself. Counter enamels provided an opportunity for the artist to truly leave their mark, and their uncovering has allowed for a new understanding and appreciation of these wonderful objects.