Studio pottery encompasses a range of object types, from tableware to one-off pottery vessels, small-scale figures to large-scale sculpture. In recent decades, it is not uncommon for ceramic artists to work on commissions for architecture and interiors, or to make forms of installation art. Yet despite this great diversity of forms, the use of a common material, clay, and its associated range of techniques, is a unifying factor for those who work with it.

The individuality that is inherent in handmade objects is an essential attribute of studio pottery and sets it apart from industrial production. This individuality – which has a humanising effect – is present both in consciously artistic 'individual pieces' and in the repeat production by hand of standardised tableware shapes, known often as 'production pottery'. Studio pottery is then in essence an anti- or at least non-industrial practice where the work is undertaken by a single person or small team in a studio or small workshop. This aspect of studio pottery distinguishes it from 'art pottery' – pottery made for artistic purposes by larger ceramic manufacturers and smaller commercial potteries from around 1870 onwards. The line between studio pottery and art pottery can nevertheless sometimes be indistinct.

Early studio potters

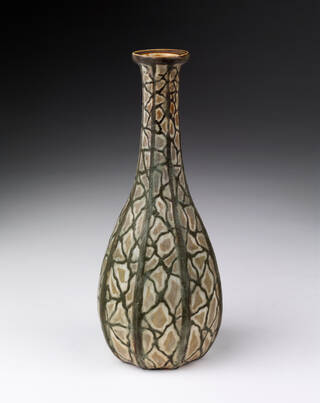

The first precedents for the resolutely independent practice of studio pottery can be found among the art potters of the late-19th century. Inspired in part by the rugged, expressive character of traditional Japanese Seto and Bizen pottery shown at the Exposition Universelle (world fair) in Paris in 1878, potters in France turned to stoneware, a durable high-fired ceramic material associated previously with everyday, functional objects. Some, like Jean Carriès, used it for sculptural purposes, while for others, including Auguste Delaherche, it became a vehicle to explore rich, high-temperature glazes, in particular streaked copper-red and purple flammeés. Ernest Chaplet also concentrated on these high-fired glazes, but on porcelain, working independently from 1887. In England, the sibling potters the Martin Brothers, worked collaboratively making salt-glazed stoneware from 1873. The eldest of the four brothers, Robert Wallace Martin, transformed jars into the caricatured birds for which the Martins are best known. In the 1900s, the younger Edwin Martin began to explore gourd-like vase forms that showed a degree of Japanese influence. Like the work of Chaplet and the French art potters, these were celebrated for wholly reflecting the art of the potter, rather than, for example, relying on painterly skill for their artistic impact.

In Mississippi, United States, meanwhile, the maverick showman and self-proclaimed 'greatest art potter on earth', George Ohr, revelled in the individuality and physicality of his output. Ohr railed against factory-made art pottery made by several hands, stating "it Don’t Take a Doz [dozen] to Accomplish Art Pottery".

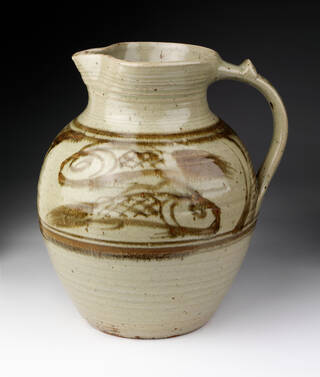

Among the first artists to become firmly associated with studio pottery was the English potter Reginald Wells. A trained sculptor, Wells began experimenting with ceramics around 1907 – 08 and built a kiln at his home at Coldrum Farm, near Wrotham in Kent. There he set about making slip-decorated earthenware based on historic local types. This interest in reviving regional traditions was characteristic of the new studio potters, as was Wells' growing enthusiasm for early Chinese ceramics. Around 1909, he moved his pottery to Chelsea, London, and in the years before the First World War, began emulating their restrained surfaces and forms. The interest among collectors, critics and potters in early Chinese wares of the Song (960 – 1279) and Yuan (1279 – 1368) dynasties was fuelled by examples being unearthed from tombs during construction work in China, and subsequently coming onto the market.

Other early studio potters were active in London in the 1910s, including Dora Lunn and Frances Richards. But it was in the 1920s that studio pottery became an identifiable movement, after the leading potters established studios in the years following the First World War. Among the most prominent of these was William Staite Murray. Murray had briefly made painted earthenware around 1915, but in 1919 he founded a workshop in Rotherhithe, London, and turned his attention to highly accomplished stoneware based initially on early Chinese types. He went on to become the pre-eminent British potter of the 1920s and '30s, exhibiting alongside the leading modern British painters Christopher Wood, Ben Nicholson and Winifred Nicholson, and becoming associated with the development of Modernism in Britian. For Murray, pottery was a connecting link between sculpture and painting, and a form of abstract art.

Bernard Leach and his circle

The most renowned of all studio potteries – the Leach Pottery – was, however, established in St Ives, Cornwall in 1920. Its founder, Bernard Leach (1887 – 1979), had spent his early childhood in East Asia before coming to England to be educated. After training at art school, he returned to Japan in 1909 with the intention of teaching etching, but there discovered pottery and was – in his own words – "seized with the desire to take up this craft". With his friend Tomimoto Kenkichi, he became apprenticed to an elderly potter, Urano Shigekichi, known as Kenzan VI, and subsequently established his own workshop in Tokyo in 1913. In his final year in Japan, Leach gained technical support from a gifted young potter, Hamada Shōji, who accompanied him to St Ives. Together, they built the first Asian-style climbing kiln in Europe (a multi-chambered kiln, built on a slope) and began making slipware, stoneware and raku (a traditional Japanese type of rapidly-fired pottery). Informed by the Arts and Crafts movement, Leach's values were profoundly anti-industrial, and he described the enterprise at St Ives as 'the counter-revolution, the refusal of the slavery of the machine.' After three years Hamada returned to Japan, where in time he established his own kiln in the traditional pottery town of Mashiko. Among the most revered and influential of potters, Hamada became closely associated with the development of the mingei (folkcraft) movement in Japan, alongside others including Tomimoto and Kawai Kanjiro.

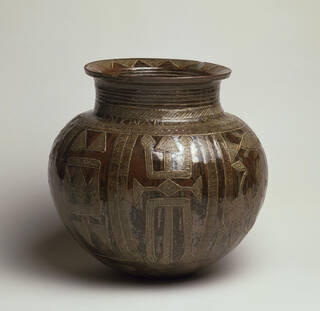

Despite technical and financial difficulties at the Leach Pottery, the influence of Leach and his work continued to grow, furthered by a succession of brilliant students who trained at the pottery, including Michael Cardew, Norah Braden and Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie. Then, in the late 1930s, Leach wrote A Potter's Book, which would have a profound and transformative influence on studio pottery in the post-war era. Published in 1940, A Potter's Book was part manual, part polemic: it gave an impassioned statement on the role of the contemporary potter and of Leach's aesthetic values and offered an enticing vision of an independent creative life. Its impact was substantial, encouraging many to follow Leach's path and establishing Leach-influenced schools of practice as far afield as the United States, Australia and New Zealand. Meanwhile, Leach's former student Cardew was drawn to Africa, working first in the Gold Coast (now Ghana) and later in Nigeria. Employed by the colonial government, he established a Pottery Training Centre at Abuja (now Suleja), where he produced stoneware inflected by Nigerian pottery traditions, working with trainees and alongside talented Gwari women potters including Ladi Kwali.

Post-war avant-garde movements

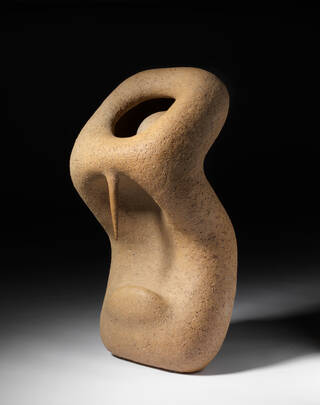

While Leach and those of his circle drew upon historical sources and made pottery that conformed to a recognised canon of forms, others in the post-war era were more radical in approach. Avant-garde schools of studio pottery in America and Japan in particular challenged convention, making sculptural ceramics in an uncompromisingly contemporary spirit and revelling in the physicality of their materials. In Kyoto, Japan, a succession of progressive groups of potters were established in the late 1940s, including the Shikōkai, and most notably the Sōdeisha (literally 'Crawling through Mud Association'), founded by Yagi Kazuo, Yamada Hikaru, and Suzuki Osamu among others. These potters reacted against the conservatism of the established ceramic community, instead exhibiting non-vessel based ceramic forms and seeking to explore 'the very limits of ceramics'.

In the United States, a similarly radical school of ceramics grew up around the Californian potter Peter Voulkos (1924 – 2002). In 1954, Voulkos founded a ceramics course at the Los Angeles County Art Institute (later Otis College of Art and Design), where he worked directly alongside his students in an atmosphere of wild and abandoned creativity. Allied with the Abstract Expressionist movement in painting, his practice placed emphasis on gesture and the processes of making. In doing so, he and his circle extended the sculptural possibilities of wheel-thrown pottery. Other avant-garde movements in ceramics followed on America's west coast. Many potters focused on colour and surface finish, producing pots that were slick and clean, following a Pop Art idiom. Others created work that was brash or self-consciously crude, with a deliberately amateurish look – a genre that became known as Funk.

In Britain, new approaches were also being taken in the post-war years. Ceramics made by Pablo Picasso in the south of France made an impact when they were exhibited in London in 1950, encouraging potters like William Newland and Margaret Hine to make lively pottery and figures with a contemporary spirit and strongly Mediterranean flavour, evident in their chosen imagery of doves, bulls and harlequins. Increasingly, potters also began to explore handbuilding methods to form their pots, rather than throwing them on the wheel, constructing them instead from coils or slabs of clay. This allowed more sculptural possibilities to be explored, producing forms that were often either organic or architectural in character. Staff and former students of the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London, including Gordon Baldwin, Gillian Lowndes and Ruth Duckworth led these new developments.

The arrival of Lucie Rie (1902 – 95) brought fresh impetus. Having fled the Nazi regime and settled in London in 1938, she brought a modern European sensibility to British studio pottery. Rie was joined in her studio by fellow émigré Hans Coper (1920 – 81) in 1946, who increasingly developed sculptural vessel forms constructed from thrown sections, which seemed poised between the contemporary and the archaic.

New directions

By the 1960s, studio pottery had become a vibrant, widespread artistic practice with a strong international community. In some countries, particularly those of Scandinavia, a close association between studio pottery and industry developed, as potters were invited to work in studios within the factories of Gustavsberg in Sweden, and Arabia in Finland, among others. But by-and-large studio potters worked independently, their ability to do so supported by teaching programmes, the sharing of information through manuals and journals, and the commercial availability of equipment and suitable materials – all a far cry from the hard-won independence of the movement's early pioneers. With studio pottery practiced widely by both professional potters and enthusiastic amateurs, it is perhaps unsurprising that a more conceptual concern for ceramics developed at its cutting edge. This is nowhere more clearly seen than in the work of the progressive group of women potters – principally Elizabeth Fritsch, Jacqueline Poncelet, and Alison Britton – who emerged from the Royal College of Art, London, in the early 1970s. These potters took the ceramic vessel as a subject for conceptual enquiry as well as formal exploration, in doing so establishing the basis of the 'new ceramics' of the 1970s and '80s.

Studio pottery has since moved forward strongly in numerous directions, despite the decline in its teaching as a separate discipline. Its development as a form of sculpture has been a dominant trend. Figurative work has seen a resurgence, and associated with this, the exploration of narratives and identity. More expansive forms of studio ceramics have also emerged, with the development of assemblages of pieces as installations, of large-scale work for public spaces, and of ceramics as a form of performance. And while the production of more utilitarian, everyday pots by the studio potter has diminished, the making of one-off individual vessels continues, and in the hands of the most accomplished – such as the Kenya-born potter Magdalene Odundo – achieves the very highest level of artistic expression.