Many familiar with the V&A’s collections may immediately think of Tipu’s tiger, one of the most famous objects in the museum today. This wooden automaton was made for Tipu himself, and was looted from his palace at Seringapatam by soldiers of the British East India Company during their final assault on Tipu’s capital in May 1799. But how did a porcelain bust of France’s most famous queen also find itself amongst the loot from that palace? And how did it end up in the V&A’s collection?

Tipu Sultan and the French Court

Tipu Sultan became ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore in 1782, in the midst of the second in a series of four wars between the Sultanate of Mysore and the army of the British East India Company, known as the ‘Anglo Mysore Wars’. At this time, there were tensions between French and British interests in India, and French troops lent some support to Tipu in his conflict with Britain as a result.

In 1783, the signing of the Treaty of Paris officially put an end to any French challenges to Britain’s interests in India. However, Tipu remained hopeful of securing French assistance in future conflicts with Britain. He therefore decided to send an embassy to France, in the hope of persuading King Louis XVI to agree to a formal alliance.

On 16 July 1788, three ambassadors from Tipu’s court arrived in Paris: Mohamed Dervish Kahn, Akbar Ali Khan, and Mohamed Osman Khan. They brought gifts for the royal couple, including cotton robes and jewellery made from diamonds and pearls. They also came with requests from the Mysore ruler, not only for the alliance itself, but also for various objects of French manufacture that he wished to have brought back to India. Amongst the items on Tipu’s wish list were items of Sèvres porcelain.

During their time in Paris, the three ambassadors made a visit to the Sèvres porcelain factory, next door to the royal gardens at St Cloud. There they were presented with a custom-made porcelain service designed especially for Tipu, with instructions given to use only floral motifs (apparently out of concern for possible cultural sensitivities regarding images of people or animals).

As well as being given gifts to deliver to Tipu, the ambassadors were also presented with gifts of their own. Amongst these were three pairs of porcelain busts of King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette (one pair for each ambassador). Speaking through an interpreter, the ambassadors apparently stated that ‘‘les bustes de leurs augustes peronnes du Roy et de la Reine leur rappelleraient à chaque instant de leur vie l'accueil gracieux et mémorable à jamais de S.M. lors de leur présentation’’: ‘‘the busts of the august persons of the King and Queen would remind them at every moment of their lives of the gracious and forever-memorable welcome of His Majesty during their presentation’’.

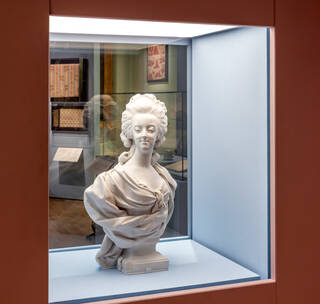

At around 40cm tall, these magnificent large-scale examples of porcelain sculpture were certainly designed to make an impression on the ambassadors. There can be no doubt of the couple’s stately power as they sit surrounded by dramatically rendered drapery. The busts are in ‘biscuit’ form, meaning the porcelain is left unglazed. Produced from the early 1750s, biscuit porcelain was an innovation of the Vincennes factory (which transferred to Sèvres in 1756) that quickly became a highly prized material, with comparisons being drawn between its surface quality and that of marble. Only the finest sculptors and modellers could turn their hand to biscuit porcelain as, with no glaze, there was no way to hide mistakes, flaws or imperfections. Indeed, the bust of Louis XVI is after a model by the great sculptor Louis-Simon Boizot (1743 – 1809) who directed the sculpture workshop at Sèvres from 1773, and its counterpart of Marie Antoinette has also been linked to Boizot on stylistic grounds but the author is unknown.

Having received a warm welcome in Paris, the ambassadors departed on 9 October 1788 on the frigate Thétis, transporting with them the many gifts they had received – including their porcelain busts.

Third Anglo-Mysore War and French Revolution

While the embassy had enjoyed a warm reception in Paris, it was only moderately successful in achieving its stated aims. Louis XVI welcomed the opportunity to strengthen commercial links with Mysore, but a formal military alliance was not forthcoming. By the start of the Third Anglo-Mysore war in 1790, France was already in the early stages of its revolution, leaving little prospect of Tipu receiving any further assistance from the French King. That war culminated in the signing of the Treaty of Seringapatam in March 1792, which saw Tipu forced to cede half of his territories to the British. Less than a year later, in January 1793, Louis XVI was executed by guillotine. Marie Antoinette met the same fate in October of that year. Tipu went on to make contact with Napoleon Bonaparte (then Commander-in-Chief of a French military expedition) when the latter landed in Egypt in 1798, but the alliance he long hoped for was never realised.

Death of Tipu and the looting at Seringapatam

On 4 May 1799, Tipu was killed when the army of the British East India Company launched their final assault on Seringapatam. Widespread looting of the city followed on an unprecedented scale, before a formal ‘Prize Committee’ was appointed to assess and distribute the contents of Tipu’s treasury. The committee’s sales of items raised ‘prize’ money totalling over £1.1m, which was shared between commanders, officers and soldiers in vastly unequal proportions according to rank. Much of the loot taken in the aftermath of the assault, however, did not pass through the ‘official’ channel of the prize committee, and many more sales, auctions and exchanges of objects between individuals took place in the days following the defeat of Tipu.

Many objects taken from Seringapatam – including the famous tiger automaton – ended up in the Company’s Indian Museum, whose collections were eventually transferred to the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A) in 1879. This was not, however, the case for the Sèvres busts of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, which did not find their way into the museum’s collection until over a century later.

John Adamson Rice

At some point following the looting at Seringapatam, a young civil servant of the British East India Company named John Adamson Rice took possession of one of the pairs of busts. John was born in Dover in 1778 to Henry and Sarah Rice (née Samson). His father was a captain in the East India Company, as were his mother’s uncles. John was educated at Westminster School and ‘instructed in writing and arithmetic’ at Finsbury Square Academy, before entering into the service of the British East India Company in 1796 as a writer, aged just 18.

On 1 October 1798, John Adamson Rice arrived in India, and some time in early 1799 he was appointed to the administrative position of ‘Second Assistant Under the Collector of Canara’. By October 1799 he was in Seringapatam, though it is unclear exactly when he arrived there. It is therefore also unclear whether he could have acquired the busts of the French royal couple in the immediate aftermath of the British assault on the city, or whether he may have purchased them some time in the following months.

However he came to acquire them, the busts were not in John’s possession for long. On 21 October 1799, John Adamson Rice died at Seringapatam, and was buried there. His death and burial were reported in a letter from the Commandant at Seringapatam, to the ‘Secretary to the Government at Fort St George’ who wrote that ‘Mr Rice who was on his way to Cannara as assistant to the Collector there died at this place yesterday evening – his remains were interred this morning and the corpse was attended to the Grave by the Chief officers and staff of this garrison’. His cause of death was not specified. The busts then appear to have been sent to England, presumably along with John’s other personal possessions.

1983 sale and ‘saved for the nation’

In 1983, the busts of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette acquired by John Adamson Rice were auctioned at Christie’s auction house in London. The provenance of these objects as former gifts to Tipu’s ambassadors was well known at this time – the catalogue for the sale stated that ‘when Tippu was defeated and killed at the sack of Seringapatam in 1799, the busts were acquired by John Rice, then in the service of the East India Company’. The catalogue also explained that after Rice’s death, the busts were ‘returned’ to England (a curious choice of words, given that the busts had never been in England previously), and passed by descent to the anonymous vendor at the 1983 sale.

The busts were purchased by a UK dealer who soon found an overseas buyer for them. When the dealer applied for an export licence to send them out of the country, however, they caught the attention of curators at the V&A, who decided to appeal to the Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art to have the objects ‘saved for the nation’.

Established in 1952, the Reviewing Committee has the power to designate an object as a ‘national treasure’ if it meets one or more of three criteria known as the ‘Waverly Criteria’: that it be ‘closely connected with our history and national life’, ‘of outstanding aesthetic importance, and ‘of outstanding significance for the study of some particular branch of art, learning or history’. In the case of the two busts, the V&A’s curators in 1983 argued that they fulfilled all three criteria, being ‘inextricably tied to the history of this country, and of its conquest and rule of India’. The Reviewing Committee at the time agreed, and the V&A was granted the opportunity to purchase the busts for the museum’s collection.

The two busts of the French royal couple have now been at the V&A for over 40 years, although 2017 saw them temporarily travel back to Paris when they were lent to the Chateau de Versailles’ exhibition Visitors to Versailles. Together, the busts of Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI present a striking visual depiction of the French king and queen, while their provenance reveals a complex history of diplomacy, conflict and colonial violence that saw them travel from France, to India, to Britain.

The authors Alexandra Watson Jones, V&A Provenance Research Curator and Simon Spier, V&A Curator of Ceramics and Glass, would like to thank Lesley Shapland at the British Library for her assistance with consulting India Office records.