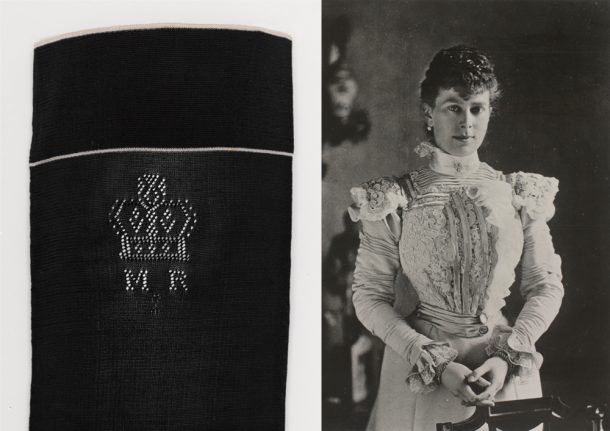

I first encountered Queen Mary several months ago when I found myself handling her stockings.

Let me explain – the stockings were among the thousands of objects in the Clothworkers’ Centre at Blythe House which I have been auditing and photographing in preparation for their upcoming move to our new Collections and Research Centre.

In one drawer of fairly plain hosiery, I came across two pairs of stockings and another single stocking all sporting a crown motif and the initials ‘M R’. After researching their date and place of manufacture, I reasoned that they must have been made for Queen Mary (1867 – 1953), information which hadn’t been noted on the catalogue record. Although pleased with my detective work, I didn’t think any more about it until I noticed that her name was cropping up on several other catalogue records. It was then that my curiosity piqued and I decided to look further into her connections to the V&A.

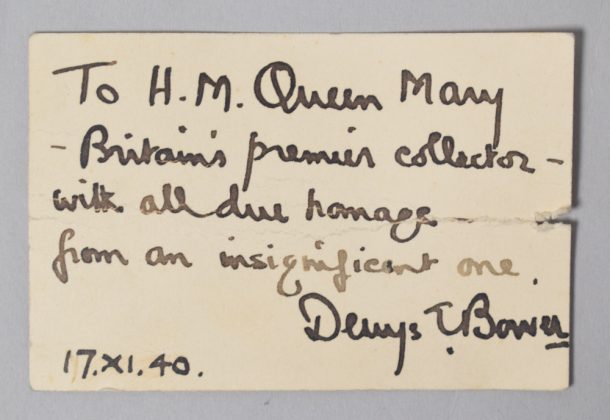

Queen Mary was the consort of King George V (reigned 1910 – 1936) and the grandmother of the current queen, Queen Elizabeth II. Like some of her predecessors, she had a lifelong interest in history and the arts, and was an avid collector of furniture, paintings and objets d’art. But unlike previous royal collectors, she also loved to personally research, organise and display her finds. Nothing delighted her more than cataloguing and labelling her latest acquisitions or discussing them with fellow collectors. She also spent years improving the documentation and arrangement of the Royal Collection, identifying misplaced treasures in the myriad rooms of the royal palaces and buying back pieces that had been sold by previous generations. Queen Mary was undoubtedly Britain’s curator queen.

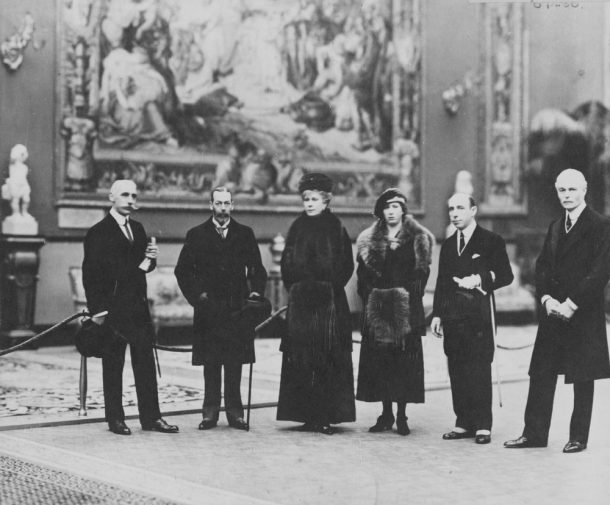

Given her interests, it is not surprising that Queen Mary loved visiting museums and galleries. She was especially fond of the V&A, perhaps because of the historic link between them – Mary’s favourite residence, Marlborough House, had been the V&A’s original home before its move to South Kensington in 1857. The Queen took a keen interest in the Museum’s work, and not just on a superficial level. She asked to be informed of new acquisitions, requested copies of publications and sought curatorial advice about pieces in her own collection. She visited frequently, spending hours strolling from one gallery to another, scrutinising and discussing the objects around her. Even in the photograph below, Queen Mary’s head is blurred, as if she was too busy looking around at the displays to keep still for the camera.

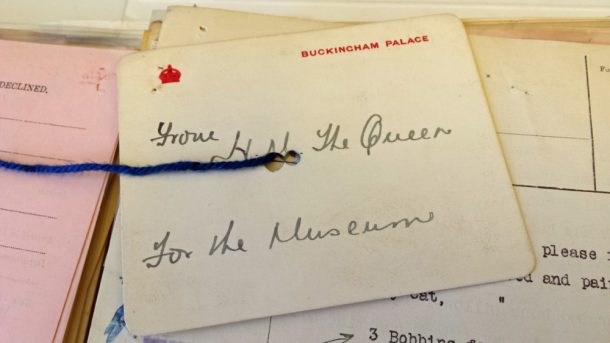

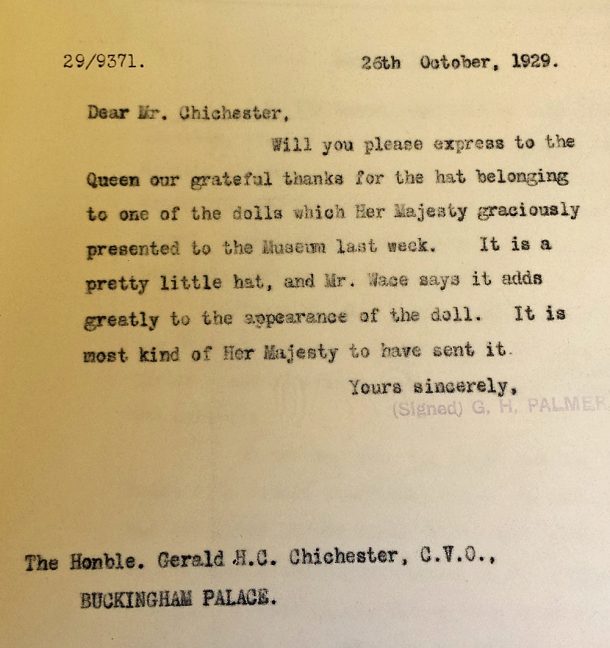

Her love for the V&A was also evident from her frequent offers to give and lend objects to the Museum. Some of these were from her own collection, some were official gifts she received as Queen, and others she bought especially for the Museum. The immense volume of documentation in the V&A Archive relating to these objects shows just how prolific her collecting was. Sometimes barely a week went by without another note from the Queen landing on the Director’s desk, such as:

You will be tired of my handwriting but I am sending you six more of the Japanese ivory masks which I have just come across. Please add them to the collection. [To Sir Cecil Harcourt Smith, 18 January, 1924]

Or:

The Maharani of Jodhpore [sic] has just sent me the accompanying beautiful Indian dress. I should like to lend it to the Indian Museum where I think it ought to have a case to itself for I think it is the best Indian gold embroidery I have ever seen. [To Eric Maclagan, 8 October 1925]

Altogether, Queen Mary presented the V&A with over 300 objects including ceramics, textiles, furniture, toys, books and drawings. While some of her offers were politely declined, the files suggest that the staff still accepted more than they really wanted!

Her gifts were certainly eclectic. Although she could be distant with her own children, she had a particular fondness for children’s toys and anything miniature. This is best demonstrated in the exquisite craftsmanship of Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House at Windsor Castle, which was made as gift for her in 1921 – 4. However, she also gave some smaller dolls’ houses and dolls to the Bethnal Green Museum (now the V&A Museum of Childhood). In fact, when she saw an unfurnished 18th-century dolls’ house on display during a visit to the Museum, she donated a set of furniture for it! She also presented a collection of miniature books and children’s books to the National Art Library and even some miniature guns to the Metalwork department.

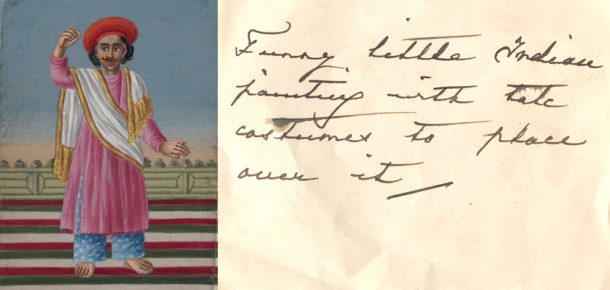

Although dedicated researcher and cataloguer, she was not always particularly knowledgeable or discerning. Her chief interest was the history of the extended royal family, and her expertise on this subject was widely acknowledged. But in other areas of collecting, her tastes were considered old-fashioned and bourgeois. She had an especially poor eye for paintings; after her death her watercolours of flower-gardens were allegedly valued at ‘a quid a piece for the frames’. Once, when informed that a painting she had attributed to Josef Nollekens was actually by Philippe Mercier, she coolly replied ‘we prefer the picture to remain as by Nollekens.’ Her attitudes to cultural difference were of their time; when she presented a set of Indian costume paintings to the V&A in 1938 she enclosed a label, in her own hand, describing one of the paintings in what now seem condescending terms as a ‘Funny little Indian painting with talc costumes to place over it.’

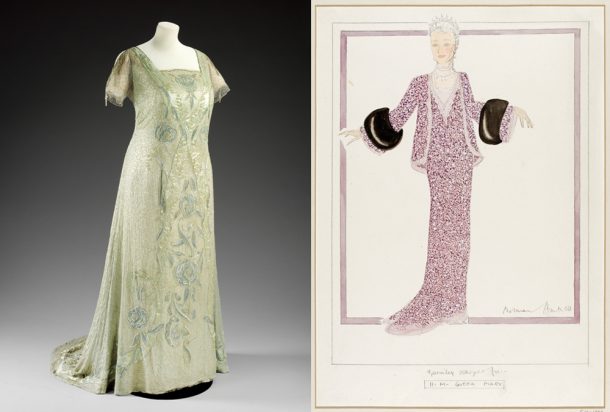

As well as pieces from her varied collection, the V&A also holds several items from the Queen’s own wardrobe. Some of these were donated by the Queen herself, others by her family or the makers who supplied them. These include five hats given by her grandson, the Earl of Harewood, a sample of the silk produced by Warner & Sons for her wedding dress, and the wooden lasts which Rayne used to make her shoes. Royal dressmakers Norman Hartnell and Elizabeth Handley-Seymour also donated drawings of outfits they designed for her.

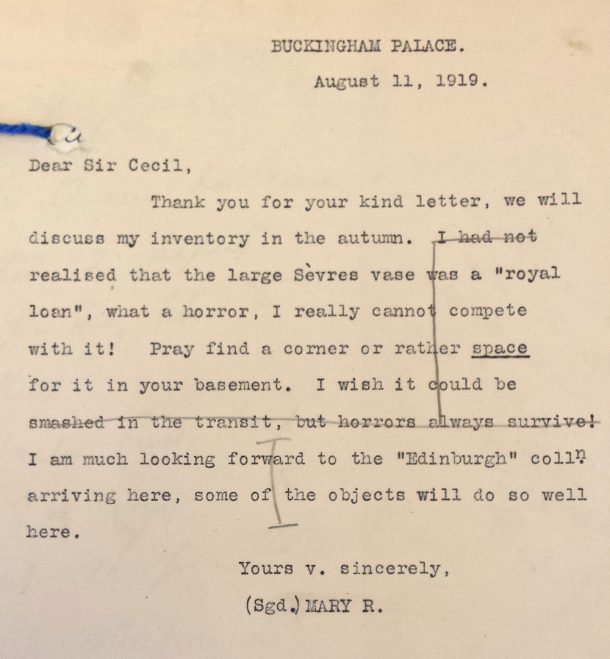

The Queen was so involved with the V&A over such a long period that she also became a kind of consultant on the Museum’s historic royal loans. Successive generations of the Royal Family had deposited some of their official gifts at the V&A on ‘permanent loan’, and over time their status had become unclear. She first reviewed these shortly after the First World War, taking some objects lent by one of Queen Victoria’s sons back to Buckingham Palace. Although, as the letter below shows, she did not want to take everything! Similarly, in the early 1950s, the octogenarian queen spent several days with Museum staff meticulously sorting through all the historic royal loans, deciding which to renew, which to return and which to transfer to other institutions. She remained a regular visitor until a few months before her death in March 1953.

If she were still involved with the V&A today, Queen Mary would undoubtedly be bringing all her organisational and problem-solving talents to bear at Blythe House. As we comb through the stores to prepare our collections for their move to Stratford, all kinds of cataloguing queries are coming to light. Some of these require a lot of research to resolve – exactly the kind of work Mary loved. ‘Oh! dear, oh! dear,’ she once despaired about a collection of royal heirlooms, ‘if only I could find the history of all these things, how interesting it w[ou]ld be, but alas there is no inventory, nothing’.

We know the feeling, Ma’am…

Very interesting read Matthew! Well done!