The first objects to be installed into the Europe galleries were the period rooms, which are now all fully built. There are three period rooms in the galleries – a 17th-century painted French room, a late 18th-century Italian mirrored cabinet and a late 18th-century Parisian cabinet. When the old galleries were de-installed, each of these rooms was taken down into at least a hundred separate parts. These parts were all individually numbered, and after conservation the V&A technicians had the mammoth job of re-building the rooms on site.

Having previously been divided across two sides of a gallery, the 17th-century French room has now been re-assembled as a complete interior. Bought by the Museum in 1903, it was originally a bedroom in the Manoir de la Tournerie, in Normandy. There is a raised bed alcove on one side of the room, across from a fireplace that was originally flanked by two windows.

The walls and ceilings of the Tournerie are made-up from painted and gilded panels, many of these framed with painted red-and-gold or blue-and-gold chequering. Large panels on the main walls are covered with stamped and painted leather. This leather was made in 1903, when the room was acquired, imitating earlier fragments. These large leather panels are unusual as a wall treatment with painted panelling, and they may have been an early replacement for paintings that were inset into the walls and subsequently sold from the house.

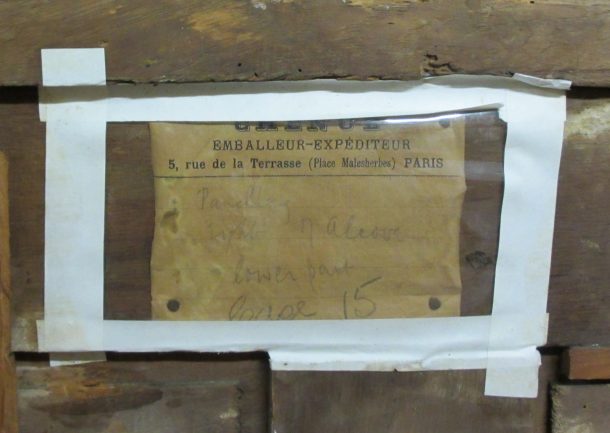

One of the most interesting things about installing the period rooms was being able to see their external structure. On the outside of the Tournerie panels there are packing labels from when the room was delivered to the V&A. It was transported by the French shipping company Chenue and this label, marked ‘Panelling / right of alcove / lower part’, suggests the difficulty which has always been involved in reassembling a room of this size and complexity from many flat panels.

This photo shows the Italian mirrored cabinet being built. Viewed from the outside the structure of the room is remarkable: a perfect self-supporting oval with curved ceiling.

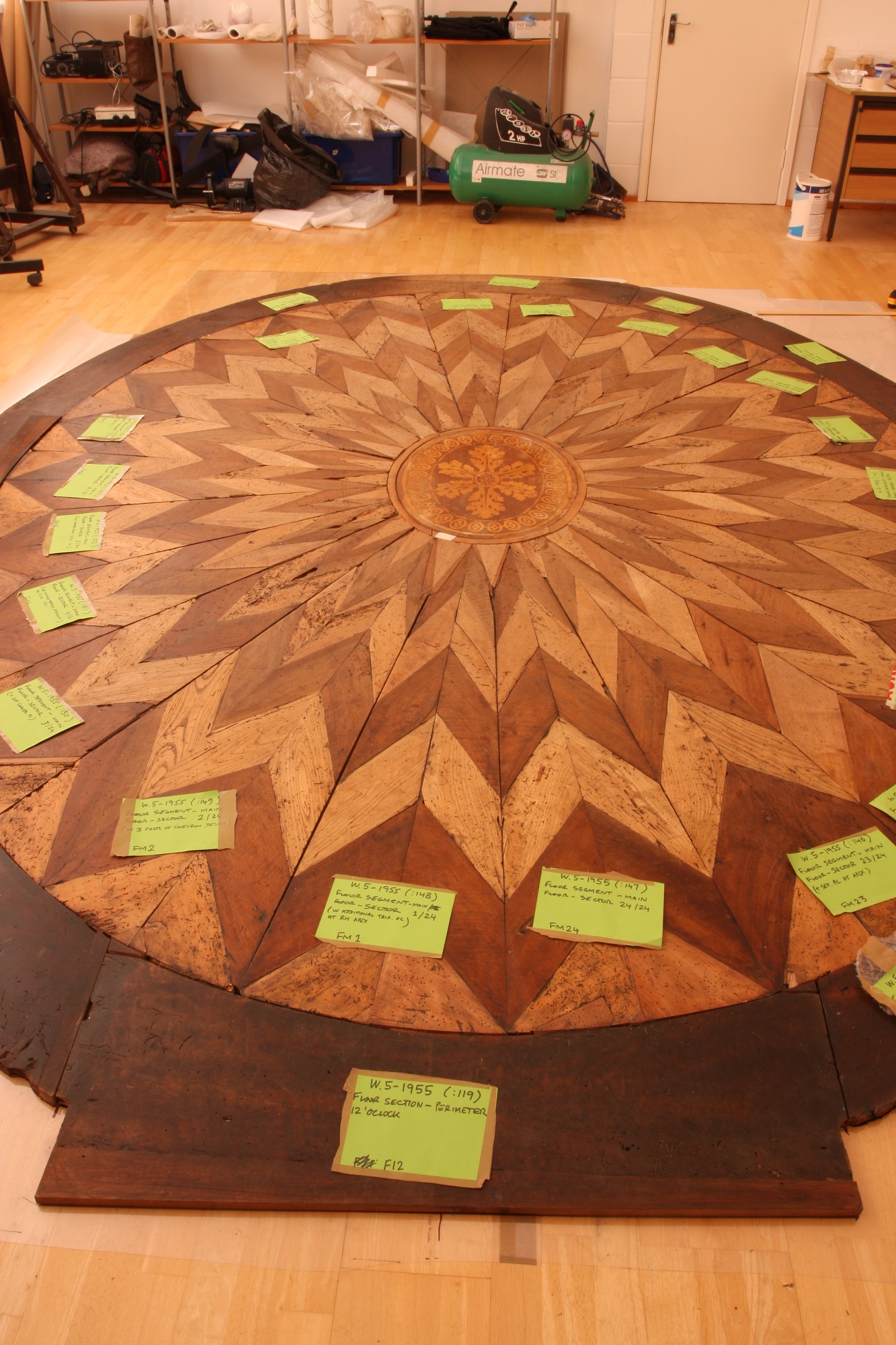

Both the Tournerie and the mirrored cabinet retain their original floors, in the mirrored cabinet the floor is made up from wedges of parquetry, fitted together along grooved edges and held in place by a central medallion.

The mirrored cabinet was given to the V&A in 1955 by Sir Chester Beatty, having been collected by his wife, Edith Beatty. Edith Beatty also had a large collection of French 18th-century furniture, including several important pieces which were given to the V&A with the room and will be on display in the Europe galleries (For example, this chair came from the Edith and Chester Beatty collection: https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/conservation-blog/the-conservation-of-marie-antoinettes-chair).

There is no record of where Edith Beatty bought the Italian cabinet, although we believe it to be from Lombardy, based on the existence of other similar small rooms in Milanese houses of the 1780s.

The Sérilly cabinet was bought by the Museum in 1869. Made in around 1778 for the hôtel particulier of the Sérilly family, the room appears to have been dismantled from the house and bought by the French dealer Paul Recappé in 1867.

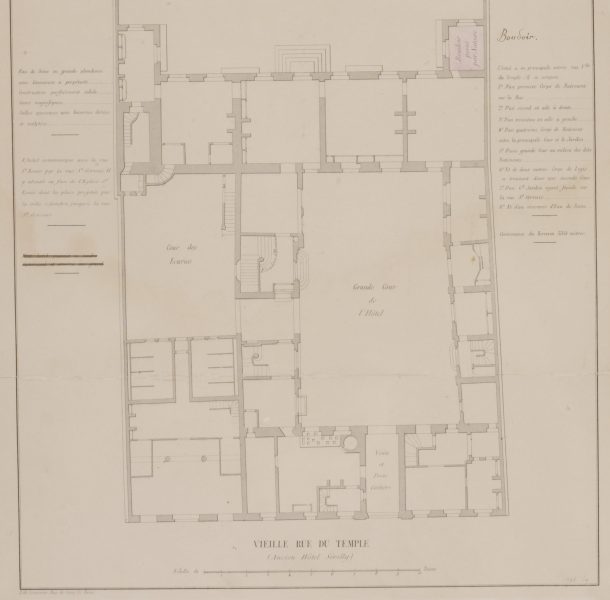

The Hôtel de Sérilly was at 106 Rue du Vielle Temple, in the Paris district of the Marais. The V&A’s tiny cabinet was attached to one wing of the house, and is visible as the pink rectangle projecting from the right-hand side of the main building, on this 1850s plan.

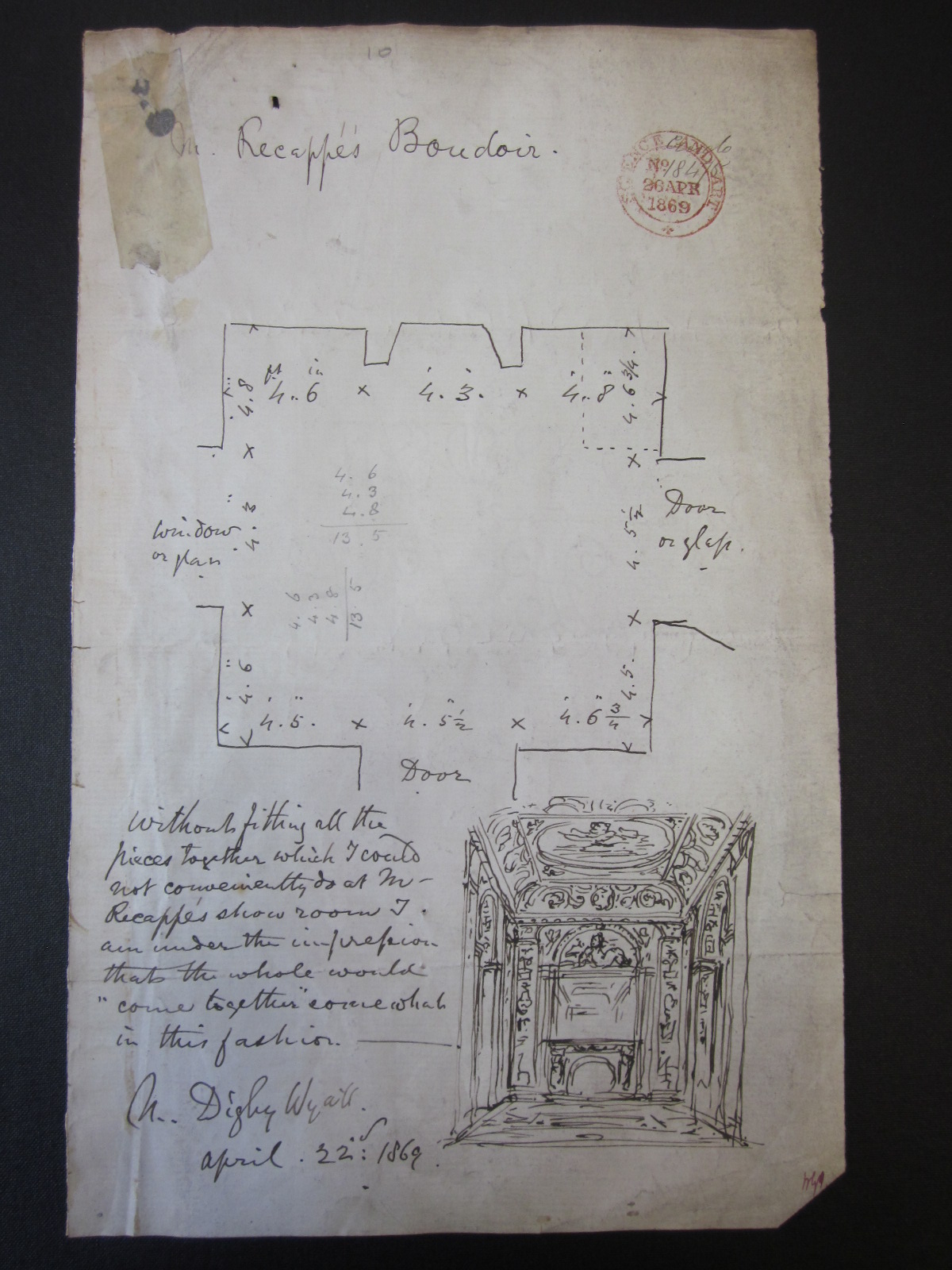

Over the course of its life at the V&A, the room has been assembled in several different configurations. The report written when it was first proposed for acquisition shows it with doors or windows on three sides of the room, although M. Digby Wyatt writes ‘Without fitting all of the pieces together which I could not conveniently do at M. Recappe’s showroom I am under the impression that the whole would “come together” somewhat in this fashion’.

Given that one of its walls adjoins the house, and the other is the fireplace wall, it is now clear the the room must only have had one window and one door. From the plans, it seems as if the cabinet was accessible only via a door from the garden, making it a perfect private and pleasurable room.

The plan of the Hotel de Serilly shows a narrow passage from the house into one corner of the boudoir – presumably this gave direct access through one of the corner concealed cupboard doors.

Dear Ashley,

Thanks very much for your comment, I’m sorry for my delay in replying. You’re right, there does appear to be some kind of passage into the room marked on the 1850s plan of the house. We aren’t sure, however, whether this apparent entrance dates from the the 18th or the 19th century. As the fireplace must have been on this wall in the original configuration of the room, any door or entrance in that spot would also have been very narrow, meaning that it probably wouldn’t have been used as the main entry into the room.

Thanks very much for pointing out this detail on the plan – I hope that you’ve been able to see the room in its new configuration in the Europe galleries.

Best wishes,

Lizzie.