Box 1

There are two boxes containing a selection of photographs which represent the major 19th and early 20th century photographic processes and techniques.

A Guide to Early Photographic Processes by Mark Haworth-Booth and Brian Coe (Victoria and Albert Museum, 1983) and Looking at Photographs by Gordon Baldwin (J. Paul Getty Museum, 1991) have been used to help define these processes.

Daguerreotype (1839 – late 1850s)

The daguerreotype was invented by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre and introduced to the public at the Academy of Sciences in Paris on August 19, 1839. It was hugely popular as a medium for portraiture until the mid-1850s. This photograph depicts two unidentified girls and it is housed in an oval mount with a papier-mâché case. It can be confidently attributed to Whitehurst as his name is blind-stamped onto the velvet case interior.

Identifying the technique

The daguerreotype is easily damaged by touching and is often protected in a leather case or frame, with a decorative mask or a glass cover. Since the image is in the form of a greyish-white deposit on a shiny silver surface, the daguerreotype has to be held so as to reflect a dark ground against which the image is seen as a positive. If the image reflects a light ground, the image appears negative. This is unique to the process and is the most easily recognised feature when the daguerreotype is in a case.

The Process

The daguerreotype is a direct-positive process. Highly polished silver-plated copper sheets are treated with iodine to make them sensitive to light. After they are exposed in a camera, the sheets are developed with warm mercury vapour until the image appears. To fix the image, the plate was immersed in a solution of sodium thiosulfate or salt and then toned with gold chloride. Exposure times for the earliest daguerreotypes ranged from three to fifteen minutes, making the process nearly impractical for portraiture. Modifications to the sensitisation process coupled with the improvement of photographic lenses soon reduced the exposure time to less than a minute.

Collodion Positive (Mid 1850s – 1860s)

The collodion positive process was invented by F. Scott Archer in 1822 and was widely used by the mid-1850s. Collodion positives are also referred to as Ambrotypes, due to a similar process developed by James Ambrose Cutting in America. This photograph has been hand tinted and is housed in a Moroccan leather case with a decorative, pinchbeck mount. Collodion positives were relatively expensive to have made, and this additional elaborate presentation suggests that the sitters were from a wealthy background.

Identifying the technique

Collodion positives are often confused with daguerreotypes. Both processes are usually found among small, cased objects which feature sharply defined images. Both were also primarily used for portraiture. However, collodion positives do not have the problematic surface reflections typical of daguerreotypes, and the highlights are soft and creamy rather than crisp. Collodion positives were easier to tint, and faster and cheaper to make than daguerreotypes. Collodion positives rapidly replaced the daguerreotype process in the late-1850s, but were replaced by tintypes and cartes-de-visites in the 1860s.

The process

A sheet of glass is hand-coated with a thin film of collodion (guncotton dissolved in ether) containing potassium iodide. The coated glass is then sensitised to light using silver nitrate, which creates a collodion negative. The back of the glass is either painted black or covered with a piece of black paper or cloth in order to achieve the effect of a positive image.

Autochrome (1904 – 1940s)

The autochrome was one of the most popular of the early colour photographic processes, both with amateurs and professionals. This is a particularly good example of the autochrome process, characterised by rich and varied colour tones. The location and the maker of this image are unknown, which is not unusual due to the widespread use of this process.

Identifying the technique

Autochromes are coloured transparent images on glass, similar to slides, that are rich and dense in natural colours. Autochromes are intended to be viewed by being held up to the light or projected onto a surface. Looking closely, images have a grainy quality because of the starch grains used in the development process. Autochromes, therefore, usually appear to have a slightly softer focus.

The process

Developed in 1904 by the Lumière brothers in France, the technique involves coating a glass plate with a mixture of potato starch grains that have been dyed in the three primary colours: red, green and blue. This is what gives the image the grainy appearance. A coat of varnish is added over this layer of grains, which is followed by a gelatin-bromide emulsion that is sensitive to the full light spectrum. The plates are then developed and washed, making a negative. This negative is placed in a chemical bath to bleach out the negative impression, before being exposed to a white light and redeveloped. This draws out a residual positive, coloured image that should be fixed, washed and then varnished.

Box 2

Calotype (1840 – about 1855)

These images are examples of photographs made with the calotype process. This process, which William Henry Fox Talbot (1800 – 77) invented in 1840 and patented in 1841, is the direct ancestor of modern photography because it creates a positive image from a negative. Unlike the daguerreotype, which is a direct positive process, the calotype negative could be used to make multiple prints. The word calotype comes from the Greek 'calos', meaning beautiful.

In 1849, B. B. Turner took out a licence to practice paper negative photography from W. H. Fox Talbot. Turner’s photographs were based on the traditionally picturesque style and subjects of watercolour painting, and exploited the camera’s ability to record the fine textures of the natural world.

Identifying the technique

There are several ways to recognise a calotype negative. The negative is made on writing paper and the image is a deep brown colour. The image becomes part of the paper (rather than lying on the surface of it), and contains fine particles of metallic silver, which cause the brown tint to the calotype positive image. Calotype prints are capable of showing quite fine detail, but can be identified by the characteristic mottling produced by the paper fibres in the negative. Mottling is most easily seen in areas of even, mid tones or at the edges between dark and light areas. The process was popular with amateur photographers, mainly for landscape or architectural work, until in the 1850s when it was superseded by the wet collodion process.

The process

A calotype was made by brushing a silver-nitrate solution onto one side of a sheet of high quality writing paper and drying it. Then, by candlelight, the sheet was floated on a potassium iodide solution, producing slightly light-sensitive silver iodide. The sheet was dried again, this time in the dark. Shortly before taking the photograph, the paper was again swabbed with silver nitrate, this time mixed with acetic and gallic acids. This made the paper very light sensitive.

The sensitised sheet could be used damp in the camera. Damp paper was more sensitive to light and therefore held a better image. Exposure of ten seconds to ten minutes was necessary, depending on the subject, weather, time of day and intensity of the chemicals employed.

At this point the image was not visible, but latent, in the paper. To develop the image, the sheet was again dipped in a bath of silver nitrate and acids. To fix the negative image, now wholly visible on the paper, the paper was washed in water, then bathed in a solution of bromide of potassium, washed in water again and dried again. The negative was then fixed with a solution of sodium thiosulphate (also known as 'hypo'). Sometimes the calotype negative was waxed to improve the transparency and retain more details, and was then printed in sunlight onto salted paper.

Salt Paper Print (1839 – about 1855 & 1890s – 1900s)

Salt prints are the earliest paper prints and were normally made by contact printing. They were usually printed from paper negatives (calotypes) but were occasionally printed from collodion negatives on glass. W. H. Fox Talbot (1800 – 77) invented the photogenic drawing process in 1840. Salt prints were an advancement of this.

William Sherlock was a talented amateur photographer and exhibited in many of the same photographic exhibitions as Benjamin Brecknell Turner (1815 – 94), but today is a relatively obscure figure in the history of photography. He documented British pastoral life in the 1850 – 60s and depicted the people who lived and worked in the countryside. Many of Sherlock's prints have faded over the years, probably because he did not rinse them thoroughly enough. A number of photographs that were once attributed to an artist named John Whistler are now believed to be by Sherlock.

Identifying the technique

A finished salt print is matt in tone, reddish brown in colour, and has no surface gloss. If toned it is purplish brown; if faded, yellowish brown. The highlights are usually white. Although the prints are quite resistent to fading caused by light, the unprotected silver image is very vulnerable to airborne pollutants, and the prints frequently fade to yellow at the edges, or all over. The uncoated paper surface is characteristic; very light albumen prints may be confused with salted paper prints, especially if faded, but the albumen print will generally show distinctly yellow highlights.

Salted paper was superseded in the 1850s by albumen paper, but salted paper enjoyed a revival in the 1890s and 1900s when it became popular with pictorial photographers. The term ‘pictorial’ referred to the artistic aesthetics of contemporary painting.

The process

A salt print was made by sensitising a sheet of paper in a solution of salt (sodium chloride) and then coating it on one side only with silver nitrate. Light-sensitive silver chloride was thus formed in the paper. After drying, the paper was put sensitive side up, directly beneath a negative, under a sheet of glass in a printing frame. This paper-negative-glass sandwich was exposed glass side up, outdoors in sunlight, i.e. it was contact printed.

The length of the exposure, up to two hours, was determined by visual inspection. When the print had reached the desired intensity, it was removed from the frame and fixed with sodium thiosulphate (also called 'hypo'), which stopped the chemical reaction. It was then thoroughly washed and dried. The print could be toned with gold chloride for greater permanence and richer tone.

Albumen Print, from a wet collodion negative (1850 – about 1900)

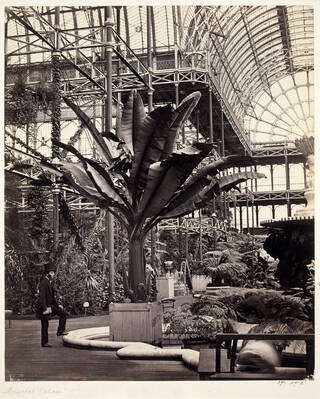

This image is an example of an albumen print made from a wet collodion negative. The albumen print was invented in 1850 by Louis-Désiré Blanquart-Evrard (1802 – 72), and until about 1890 it was the most popular type of photographic print. Philip Delamotte was commissioned to document the reconstruction of the Crystal Palace exhibition building at Sydenham in 1854. The bright light of the glass interior made it possible to take interior 'news' photographs.

Identifying the technique

This photograph can be identified as an albumen print by the slight sheen on the top surface. The fixed albumen print had a reddish-brown image color; residual silver compounds in the albumen reacted with sulphur compounds in the atmosphere to produce a yellow stain in the whites, or highlights, of the print. This yellowing provides a useful means of distinguishing a lightly coated albumen print, of the sort common in the 1850s, from a salted paper print, in which the whites would normally be clean.

An albumen print can sometimes be identified as being produced from a wet-collodion negative. The easiest way to do so is to find white dots on the print, where dust or other impurities have stuck into the collodion. Occasionally, when the collodion has been poured unevenly onto the glass plate, the print can appear streaky, reflecting the varying thickness of the collodion. The collodion process produces crisp, grainless prints that have more detail than the calotype and generally a much richer tone.

The process – Wet Collodion Negative

The wet collodion process was invented in 1848 by Frederick Scott Archer (1813 – 57). It was prevalent from 1855 to about 1881. Wet-collodion-on-glass negatives were valued because the transparency of the glass produced a high resolution of detail in both the highlights and shadows of the resultant prints and because exposure times were short, ranging from a few seconds to a few minutes, depending on the amount of light available.

Collodion is guncotton (nitrocellulose) dissolved in ethyl alcohol and ethyl ether. In the wet- collodion process, collodion was poured from a beaker onto a glass plate and tilted to quickly produce an even coating. When the collodion had set, but not dried, the plate was made light sensitive by bathing it in a solution of silver nitrate. This combined with the potassium iodide in the collodion to produce light-sensitive silver iodide. The plate in its holder was then placed in the camera for exposure while still wet – hence the name of the process. After exposure the plate was immediately placed in developer and the image became visible in a few seconds. When development was complete the developer was then washed off with clean water and the plate was fixed in a solution of sodium thiosulphate. Immediate developing and fixing were necessary because, after the collodion film had dried, it became waterproof and any subsequent solutions could not penetrate it.

The process – Albumen Print

An albumen print was made by floating a sheet of thin paper on a bath of egg white (albumen) containing salt, which had been whisked, allowed to subside, and filtered. This produced a smooth surface, as the pores of the paper filled with albumen. After drying, the albumenised paper was sensitised by floating it on a bath of silver nitrate solution or by brushing on the same solution. The paper was again dried, but this time in the dark. This doubly coated paper was put into a wooden, hinged-back frame, in contact with a negative. The negative was usually made of glass but occasionally of waxed paper. After printing (which could take from a few minutes up to an hour or more), the resultant proof, still unstable, was fixed by immersing it in a solution of sodium thiosulphate and water. It was then thoroughly washed, to prevent further chemical reactions, and dried.

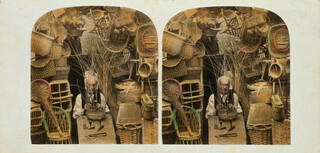

Stereographs (1850s – 1920s)

Stereographs, an early form of three-dimensional photographs, were the first ever mass- produced photographic images sold. They were major tool for popular education and entertainment in the latter part of the 19th century. The genre owes its origins to Sir Charles Wheatsone (1802–1875) in 1838 and Sir David Brewster (1781–1868), who invented an early form of the stereoscope (used to make stereographs) in 1849. The stereoscope was improved by Jules Duboscq, who made stereoscopes and stereoscopic daguerreotypes. He is also the maker of a famous picture of Queen Victoria that was displayed at The Great Exhibition in 1851.

Identifying the technique

Stereographs were a popular format for the presentation of albumen photographs (see Albumen print). Stereographs consist of two photographs of the same object, taken from slightly different angles, which were then fixed side-by-side on a piece of cardboard. The images were often hand-painted or tinted. Stereographs are intended to be looked at through a stereograph viewer. This merges the two images to make one, three-dimensional image.

The process

The stereoscope is an instrument in which two photographs of the same object are taken from slightly different angles. When they are simultaneously presented, with one image to each eye, the images merge to become one, three-dimensional scene.

Cyanotype (1842 – present)

This image is an example of a cyanotype photogram, or blueprint. The cyanotype process was invented by the astronomer and scientist Sir John Herschel (1792 – 1871) in 1842. Anna Atkins trained in botanical illustration but later turned to the ‘beautiful process of cyanotype’. She quickly realised the benefit of using this process to record specimens of plant life. In 1843, Atkins became the first person to print and publish a photographically illustrated book, British Algae, Cynotype Impressions, Part 1.

Identifying the technique

Images produced by the cyanotype process are bright blue with a matte surface. Aside from plant matter, typical subjects included architectural and engineering drawings (popular in the 1880s) and snapshot negative imprints. The cyanotype process was often used it was often used by amateurs for ‘proofing’ snapshot negatives in the 1880s and 1890s.

The process

The process developed from the discovery iron salts being light sensitive. A sheet of paper was brushed with iron salt solutions and dried in the dark. The object to be reproduced – often a plant specimen, a drawing or a negative – was then placed on the sheet in direct sunlight. After about 15 minutes, a white impression of the subject formed on a blue background. The paper was then washed in water where oxidation produced the brilliant blue – or cyan – that gave the process its name.

Photogravure (about 1880 – 1940s)

Photogravure, also known as heliogravure, is arguably the finest photomechanical means for reproducing a photograph in large editions. It was invented by W.H. Fox Talbot (1800 – 77) in 1858 and came into commercial use around 1880, after improvements by the Austrian printer Karel Klic (1841 – 1926).

The process was used for the printing of facsimile copies of paintings (often coloured), as well as for quality reproductions of the work of many of the best-known pictorial photographers in the 1890s and 1900s. The quarterly photographic journal Camera Work, published by Alfred Stieglitz from 1903 to 1917, is known for its many high-quality photogravures and for its editorial purpose to establish photography as a fine art.

This photogravure by P.H. Emerson first appeared in his book Pictures of East Anglian Life (1888). It was part of his vigorous opposition to prevailing tastes in art photography, represented by crude combination printing, glossy albumen papers, wholesale retouching and disregard for the aspect of natural conditions.

Identifying the technique

Photogravure registers a wide variety of tones, through the transfer of etching ink from an etched copper plate to special dampened paper run through an etching press. The unique tonal range comes from photogravure's variable depth of etch – the shadows are etched many times deeper than the highlights. Unlike half-tone processes which merely vary the size of dots, the actual quantity and depth of ink wells are varied in a photogravure plate, and are blended into a smooth tone by the printing process.

The process

The photogravure process depends on the principle that bichromated gelatin hardens in proportion to its exposure to light. A tissue was coated on one side with gelatin sensitised with potassium bichromate. It was exposed to light under a transparent positive, which had been contact printed from the negative of the image to be reproduced.

When wet, this tissue was firmly pressed, gelatin side down, onto a copper printing plate that had been prepared with a thin, even dusting of resinous powder. In warm water, the tissue- paper backing was peeled away and those areas of the gelatin that had not been exposed to light dissolved. The copper plate with its remaining unevenly distributed gelatin coating was then placed in an acid bath.

Where the gelatin remained thick (the highlights of the print to come), the acid ate away the metal slowly; where the gelatin was thin or absent, the acid bit faster. The plate was therefore etched to different depths corresponding to the tones of the original image. When inked, the varying depths held different amounts of ink. The inked plate was then used in a printing press.

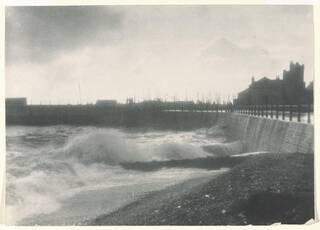

Carbon Print (about 1860 – 1930s)

Carbon prints were patented in 1855 by Alphonse Louis Poitevin (1819 – 82) and improved in 1858 by John Pouncy (1818 – 94). However, they only became fully practicable in 1864 with the patented process and printing papers of Joseph Wilson Swan (1828 – 1914).

Paul Martin pioneered candid street photography in London when, in the early 1890s, he began using a camera disguised as a parcel to photograph people unawares. Here, Martin has turned the camera to the landscape rather than its inhabitants.

Identifying the technique

Carbon prints show dense, rich, glossy tones that are either black or a deep brown in colour. Various pigments were used to give a greater range of colours (such as dark blue, green and violet). The prints also show slight relief contours (thickest in the darkest areas) as a result of the process used. The most important feature of a carbon print is its permanence; it contains no silver impurities that can deteriorate. Carbon printing was much in use for book illustrations and commercial editions of photographs in the 1870s and 1880s.

The process

A sheet of lightweight paper is coated with gelatin containing potassium bichromate and a pigment – sometimes carbon black, hence the name of the process. Gelatin becomes insoluble when exposed to light, proportionately to the amount of light received. This lightweight paper is exposed in daylight, placed under, and in contact with, a negative. This exposure is timed, as the dark-coloured paper does not show an emerging image. The dense part of the negative protects the carbon ‘tissue’ from light and keeping the gelatin soluble. Elsewhere, in proportion to exposure, the gelatin hardens.

In order to wash away the unhardened gelatin and reveal the image, the face of the exposed carbon tissue is squeezed in contact with a second sheet of gelatin-coated paper. This ‘gelatin sandwich’ is then soaked in warm water. The paper floats free and the unhardened gelatin washes away, leaving the image attached to the second sheet. The sheet is then immersed in water containing alum, which hardens any remaining gelatin and removes any yellowish bichromate stains.

The carbon image can be transferred to practically any surface: glass, ceramics, wood, leather, metal, as well as all kinds of paper.

Platinum Print (1873 – about 1920)

The process for making platinum prints was invented in 1873 by William Willis (1841 – 1923). Willis continually refined it until 1878, when commercially prepared platinum papers became available through a company he founded.

In 1897, Queen Victoria’s Jubilee year, Sir Benjamin Stone announced the formation of the ‘National Photographic Record Association’. Its aim was to record Britain’s ancient buildings, customs and other ‘survivals’ of historical interest. The Tynwald court, founded in 1979, is said to be the oldest parliament in continuous existence. It met annually on Tynwald Hill on July 5th to proclaim new laws.

Identifying the technique

Platinum prints are recognisable by their subtle tonal variations, the plain paper surface and permanence of the image. They are characterised by rich black tones and completely neutral, almost silvery-grey mid-tones.

The process

The process depends on the light sensitivity of iron salts. A dried sheet of paper, sensitised with a solution of potassium chloroplatinate and ferric oxalate (an iron salt) is contact printed under a negative in daylight until a faint image is produced by the reaction of light with the iron salt.

The paper is developed by immersion in a solution of potassium oxalate. This solution dissolves out the iron salts and reduces the chloroplatinate salt to platinum, in those areas where the exposed iron salts had been. So, an image in platinum metal replaces one in iron metal. By developing the print in a hot developer, a warmer, almost sepia platinum image is produced. The paper is washed in a series of weak hydrochloric baths to remove any excess iron salts and the yellow stain, which forms in the earlier steps. Finally, the print is washed in water.

Platinum printing went out of fashion after the First World War due to a dramatic rise in the cost of the metal. The process was partly replaced by the cheaper palladium printing process. In recent years platinum printing has been revived by some photographers.

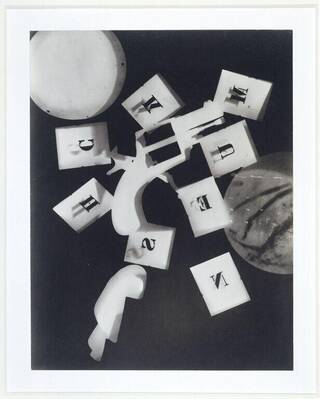

Photogram (1830s – present)

A photogram is a type of photograph made without a camera or a lens. Camera-less techniques were explored at the dawn of photography in the 1830s, were popular again during the 1920s, and have been rediscovered by contemporary image-makers in the midst of the digital age.

Man Ray was an artist of enormous international standing, who worked in many media including photography. He began to make ‘rayographs’, the photograms he named after himself, when he moved to Paris in 1921. The photogram process was linked to his interest in Surrealist photography, in which the photographer cedes control of the final outcome of the image. Photograms represent ordinary objects in an ambiguous way, capturing their forms and shadows rather than describing their structural or tactile qualities. By concentrating on the play of light and shadow, the most familiar of everyday objects take on a strange and unexpected character.

Identifying the technique

The usual result of the photogram process is a negative shadow image which shows variations in tone, depending on the transparency of the objects used. Areas of the paper that have received no light appear white; those exposed through transparent or semi-transparent objects appear grey.

The process

Some of the first photographic images made were photograms. William Henry Fox Talbot called these ‘photogenic drawings’, which he made in the 1930s by placing leaves and pieces of material such as lace onto light-sensitive paper, then leaving them outdoors on a sunny day to expose. This produced a dark background with a white silhouette of the object used. In a darkroom, objects are arranged on photographic paper and then exposed with light, usually by switching on an enlarger or another artificial light source. The material is then processed, washed and dried.

To find out more about the photogram you might also like to look at Garry Fabian Miller’s work Year One, 2005-06 in the wooden cabinet in the Prints & Drawings Study Room and consult the book Shadow Catchers: Cameraless Photography by Martin Barnes (Merrell, 2010).

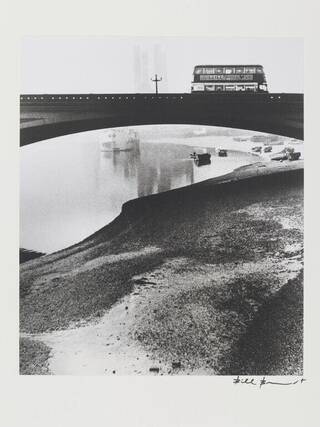

Gelatin silver print (about 1880 – present)

Bill Brandt (1904 – 83) is one of the finest British photographers of modern times. He photographed with imagination, compassion and humour, presenting vivid interactions of social life. Though born in Germany, he moved to Britain in 1933 and later renounced his German heritage. His best known work was made in Britain, where he reinvigorated the major artistic genres of portraiture, landscape and the nude. This photograph was taken on Battersea Bridge in south London. Battersea Power Station, still a hallmark of south London’s skyline, is visible in the background. This photograph has been made with high contrast, which, combined with the foggy weather, evokes a sense of drama. The V&A holds over 600 prints by Bill Brandt, which you can request in the Prints & Drawings Study Room.

The gelatin process superseded the more complex wet collodion process and revolutionised the world of photography.

Identifying the technique

Since the rise of this process in the late 19th century, manufacturers have offered a great variety of paper suitable for gelatin silver printing. Thus, the tones and surface gloss of gelatin silver prints varies. Generally, however, the tone of is neutral black. They can also be either be a cool blueish tone or a warm brown tone, depending on how they have been printed. Highlights are white unless the underlying paper support has been tinted. Gelatin silver prints often have a high surface gloss.

Photographers from the 1880s and afterward did not normally coat their own papers but obtained them from commercial sources. Gelatin silver prints had generally displaced albumen prints in popularity by 1895 because they were more stable, did not yellow, and were simpler and quicker to use.

The process

The gelatin print is a developing-out process; after a brief exposure to a negative, the print is immersed in chemicals to allow the image to develop. However, it can also be a printing-out process, similar to the albumen process. With either method, gelatin, an animal protein, is used as an emulsion to bind light-sensitive silver salts – usually silver bromides or silver chlorides – to a paper or other support. For the developing out process, the image is exposed under a negative and then immersed in chemicals to allow the image to develop or emerge. For the printing out process, the photograph is placed under a negative and under a light until the image appears in its final form.

Solarisation (1840 – present)

The solarisation effect is one of the earliest known effects in photography. In 1840, the astronomer and scientist Sir John Herschel (1792 – 1871) observed the reversal of an image from negative to positive by extreme over-exposure.

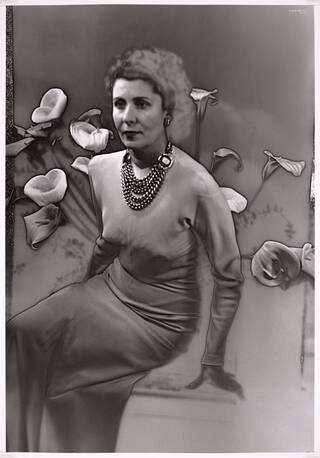

Ilse Bing was one of several successful European women photographers of the inter-war period. Born into a Jewish family in Frankfurt, she initially pursued an academic career, before moving to Paris in 1930 to concentrate on photography. She first experimented with solarisation in 1934. This partly solarised gelatin-silver print of Baroness Van Zuilen uses light and stark outlines to surreal effect. The lilies behind are abstracted and frame the sitter as she appears to float in her elegant outfit.

Identifying the technique

Solarisation is a phenomenon in photography in which the image recorded on a negative or on a photographic print is wholly or partially reversed in tone. Dark areas appear light and light areas appear dark. A narrow band is formed at the boundaries between highlight and shadow areas. If the film negative is treated, the line is light, which produces a dark line in the print. When the print itself is processed it produces a white line around areas of high contrast.

The process

Solarisation happens when negatives are exposed to specific amounts of light in the darkroom during developing or printing, producing partly reversed images. The effect was usually caused by exposing an exposed plate or film to light during developing.

C-type Print (1942 – present)

The term C-type print stands for chromogenic colour print. The first commercially available chromogenic print process was Kodacolor, introduced by Kodak in January 1942. Kodak introduced a chromogenic paper with the name Type-C in the 1950s, and then discontinued the name several years later. The terminology Type- C and C-print have remained in popular use since this time.

In the late 1980s, British photographer Nick Waplington spent four years documenting the daily lives of two families on a council estate in Nottingham, England. Rather than embracing the contemporary photographic conventions of social realism, Waplington chronicled the lives of these families in saturated colour, capturing an intimate narrative with poignancy and an unexpected humour.

Identifying the technique

Chromogenic colour prints are full-colour photographic prints made using chromogenic materials and processes. It is the most common type of colour photographic printing.

The process

Chromogenic colour images are composed of three main dye layers – cyan, magenta, and yellow – that together form a full colour image. A light sensitive silver halide emulsion is present in each layer, which makes a silver image during exposure. After exposure, this silver image is developed in a special colour developer which contains a dye coupler. During this reaction, the colour developer oxidises areas of exposed silver and reacts with the dye coupler. This is the chromogenic reaction: the union of the oxidised developer and the dye coupler form a colour dye. A series of processing steps follow, which remove the remaining silver and silver compounds, leaving a colour image composed of dyes in three layers.