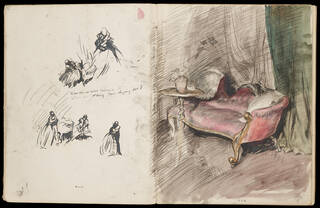

Clarke Hall began to draw Wuthering Heights from around 1899. She placed Heathcliff and Catherine not in their eponymous shared childhood home but in her own surroundings, the historical properties of Great Tomkins and then Great House estate and farm where she lived as a newly married woman in rural Upminster, Essex. Some scenes she depicted were not explicitly taken from the text of the novel, while others are more faithful renderings relocated into her home. On one page of a sketchbook dated to 1900, she choreographs multiple small sketches of Heathcliff and Catherine in quick strokes of black ink, embracing on the same settee depicted in a detailed drawing on the other side of the page. Inside the arc of these images Clarke Hall wrote down a quotation from the dramatic scene they illustrate, spoken by Catherine: ‘Let me alone! If I’ve done wrong, I’m dying for it’.

These words are Catherine’s response to Heathcliff’s condemnation of her choice to marry Edgar Linton, the conventional and ‘civilised’ gentleman who is the exact opposite of the passionate and elemental Heathcliff she claimed as her soulmate. He demands: ‘Why did you betray your own heart, Cathy?’ It is striking that Clarke Hall focused on this scene because it draws attention to the devastating impact of her own recent marriage in 1898, aged 19, to barrister William Clarke Hall (1866 – 1932).

Edna Clarke Hall was a prodigal and prize-winning talent at the Slade School of Fine Art from 1893 to 1899, aspiring to pursue a professional career as an artist. Yet her husband did not keep his promise to support her vocation, disappointed by her lack of interest in emulating large-scale late Victorian oil paintings in an academic style. To avoid criticism, Clarke Hall would often conceal her work and set up a private studio space at the top of a barn on Great House’s farm. She looked back with nostalgia to her years at the Slade, just as Catherine of Wuthering Heights longed to be a girl again, ‘half savage and hardy, and free’.

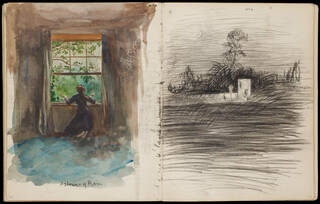

Clarke Hall identified with the wilful and vibrant Catherine, who is framed unsympathetically by the narrative voice of her practical servant Ellen Dean. ‘Why does Catherine hold the imagination?’ the artist wrote in her memoir, ‘You could realise that she was wanting to expand, that she was starving for something else that could not be given to her’. Clarke Hall made drawings that suggest the confinement that both she and Catherine experienced in their respective domesticity. She repeatedly draws windows in her sketchbook, their frames often heavily outlined in ink or enclosing restless skies in high-keyed watercolours. Beside them the figures of women look out to the world beyond the glass. Obliged to practice her art secretively and at home, Clarke Hall echoed the way Emily Brontë and her sisters wrote their novels over half a century before.

Clarke Hall’s responses to Wuthering Heights demonstrate her persistent commitment to her creative expression. She collected vintage clothing from London’s East End and negotiated a lack of models by drawing herself, or sometimes her sister Rosa, as both the adult Catherine and Heathcliff. This doubling embodies the characters’ own belief in their inseparability: Catherine memorably declares ‘I am Heathcliff’, while Heathcliff laments that he cannot live ‘without my soul’ after her death. At the same time, it alludes to the equation made by Clarke Hall and her friends as young women of artistic freedom with unconstrained masculinity. Close friend Ida Nettleship (1877 – 1907) had encouraged her in a letter of 1896 to pursue art single-mindedly and ‘be a man for a time’. Within the world of Wuthering Heights, Clarke Hall could experiment with this advice through fantasy, playfully adopting different gender roles.

Heathcliff and Catherine’s otherworldly connection to nature aligned with Clarke Hall’s own romantic view of the transcendent qualities of the natural world, which she would later channel through her Poem Paintings. The etching Catherine’s Dream (1920) shows Catherine almost impressed into the earth, the shape of the ground also suggesting the contours of a bed. This image evokes the character’s transgressive renunciation of heaven in favour of her beloved moors. ‘Heaven did not seem to be my home’, she says of her dream, ‘and the angels were so angry that they flung me out into the middle of the heath on the top of Wuthering Heights; where I woke sobbing for joy’. It is implied at the end of the story that Heathcliff and Catherine’s reunited ghosts haunt the landscape, just as they haunted Clarke Hall’s imagination.

After establishing a studio in London from 1922, Clarke Hall took printmaking classes at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. She started to reproduce many scenes from Wuthering Heights as etchings, returning to her sketches and making multiple impressions of the same image. Exhibited much more frequently throughout the 1920s and 1930s, her depictions of the novel found an external audience. They became some of her most popular and enduring works of art and began to enter public collections. These works felt so personal to Clarke Hall that their removal from her proximity was a wrench. She wrote in 1938 to Lawrence Haward (1878 – 1957), curator of Manchester City Art Galleries, that they had ‘lived with me for so long through so many adventures and reverses’.

With a considerable number now residing in museums and galleries like the V&A, Clarke Hall’s Wuthering Heights pictures constitute a formidable body of work, bearing testament to the solace of the imagination. They weave together the art of two singular women separated by time and geography, uniting the searing force of Emily Brontë’s novel with Clarke Hall’s artistic powers in bringing it to life.

Discover more illustration in the V&A's collections.