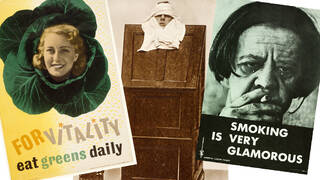

1. Wash your hands

An understanding of the importance of hand washing to prevent the spread of infectious diseases has been known since the 18th and 19th centuries thanks to the discoveries by medical pioneers, such as Charles White, James Young Simpson, Ignaz Semmelweis, Alexander Gordon, Oliver Wendell Holmes and Florence Nightingale. But despite this, it seems we always need to be reminded. Here we have a poster from the 1920s, issued by the Health and Cleanliness Council, promoting the use of soap and water, though we are probably more familiar with recent hand washing campaigns around the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

2. Wear a coif

Up until the end of the 17th century, it was common for women to wear a close-fitting cap – a kind of fabric helmet – called a 'coif' (they fell out of fashion with men in the 14th century). It was worn mainly indoors or outside in public under a hat as a way to protect against chills and disease. Plain linen versions were worn by the working class, whilst more luxurious versions, embroidered in coloured silks and embellished with precious metal threads and pearls, were worn by the upper classes.

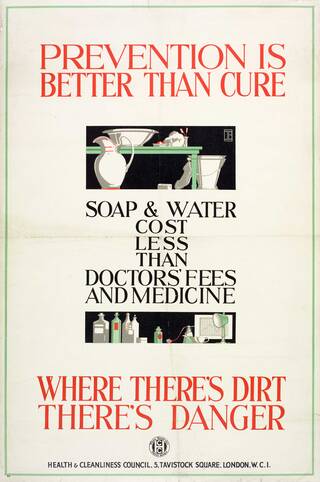

3. Move to Milton Keynes

Relocating can have health benefits, especially if that move is from a large polluted city to a small town in the countryside. This poster from 1973, issued by Milton Keynes Development Corporation, promotes moving to the new town of Milton Keynes in South east England as a way of improving your health.

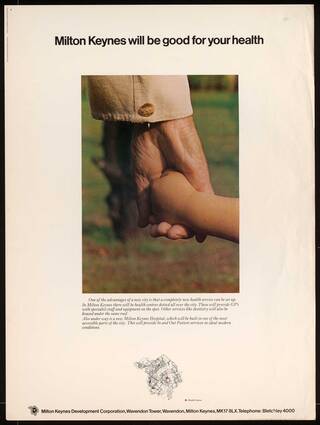

4. Tie your shoes laces

Another poster, this time reminding us of the importance of tying our shoe laces. Issued by the Ministry of Labour and National Service during the Second World War, its hard-hitting message warns us of the damage an untied shoe lace can do both to ourselves and the war effort.

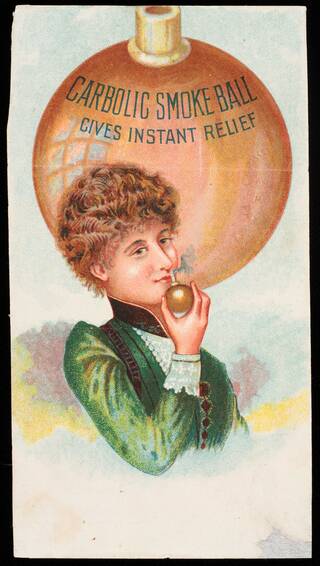

5. Use a Carbolic Smoke Ball

In 1891, the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company ran a series of newspaper adverts promoting a product called the 'smoke ball', which they claimed was a cure for influenza. The smoke ball was a rubber ball containing carbolic acid (now known as phenol) with a tube that was inserted into the nose and squeezed to release the vapours. So confident was the company with their product that they offered £100 (equivalent to about £16,000 in 2025) to anyone who contracted the flu after using it:

£100 REWARD will be paid by the CARBOLIC SMOKE BALL CO. to any Person who contracts the Increasing Epidemic, INFLUENZA, Colds, or any Diseases caused by taking Cold, after having used the CARBOLIC SMOKE BALL according to the printed directions supplied with each Ball.

£1000 is deposited with the ALLIANCE BANK, Regent Street, showing our sincerity in the matter.

A legal case was brought against them after they refused to honour the promised payout to a Mrs. Louisa Elizabeth Carlill, who caught the flu on 17 January 1892 despite using the product three times daily for nearly two months. The company attempted to claim it was not a serious contract, but they lost the case, which is still frequently referenced in matters of contract law.

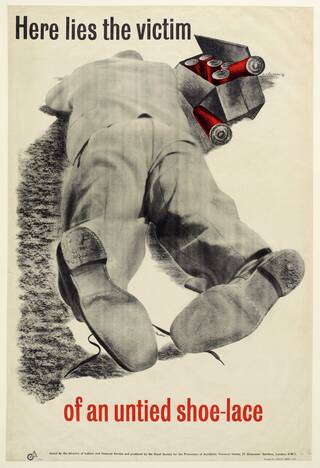

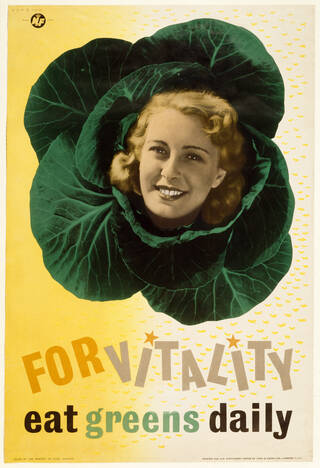

6. Eat your vegetables

A month after the outbreak of the Second World War, the Ministry of Food launched the infamous ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign, encouraging Britains to use every spare inch of land to grow fruit and vegetables. The aim was to replace the deficit caused by the lack of imported food, keep the nation healthy and boost morale. Recipe ideas were shared widely in an effort to improve nutrition and provide ideas for bulking out meals during rationing. Characters such as 'Doctor Carrot' and 'Potato Pete' were conjured up to make eating vegetables appealing to children. Clearly the anthropomorphising of vegetables was a successful tactic as the overall health of the nation actually improved during the war years.

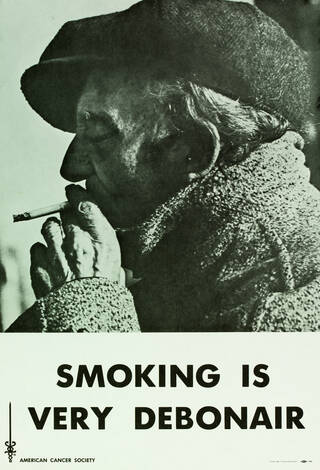

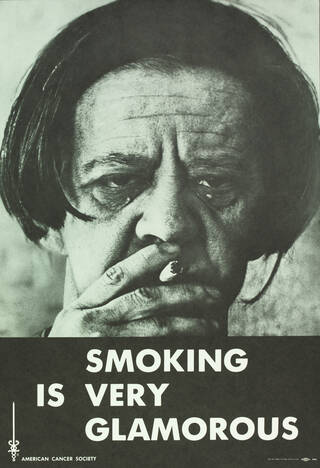

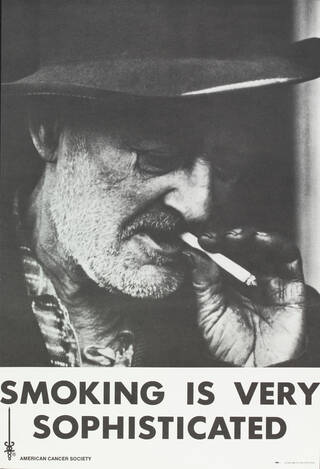

7. Quit smoking

An anti-smoking poster campaign by the American Cancer Society in the 1970s aimed to counteract the image portrayed by many Hollywood actors of smoking being sophisticated, sexy and glamorous. Using images of haggard, unkempt people with cigarettes in their mouths alongside contradictory statements, such as 'SMOKING IS VERY DEBONAIR', was intended to stress the consequences of smoking on physical appearance.

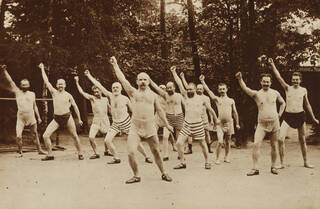

8. Visit a health resort

Andrew Pitcairn-Knowles (1871 – 1956) was a pioneering photographic journalist with an eye for detail, timing and geometry that resulted in his images having a quirky, almost surreal quality.

Having travelled around Europe in the early 20th century photographing the leisure activities, sports and customs of the period, Pitcairn-Knowles founded Riposo (Italian for 'rest' or ‘repose’) in 1913, a Health Hydro & Dietetic Sanatorium in Hastings, Sussex, England. It was one of the first health resorts in the UK to practice 'Nature Cure', or 'Naturopathy'. The basis of most alternative therapies, one of the fundamental principles was that illness results from the accumulation of toxins or waste in the body because of an 'unnatural way of living'.

Pitcairn-Knowles promoted a variety of treatments: Hydropathy (water and steam applications), Heliotherapy (sun, air and light treatment), Dietetics (food and nutrition), Physical Culture (exercise, manual therapy and massage), the Guelpa Cure (fasting, reduced diet and purging), and the Schroth Cure (sleeping in wet sheets followed by a 'dry diet' consisting of four meals a week where only rice, sago – a type of starch extracted from palms, porridge or potatoes – were allowed). The only fluids allowed by patients on the Schroth Cure was wine, limited to four days a week, which helped them to ‘overcome the weariness that the dry diet caused'.

Many diseases were treated in Riposo, including obesity, mental depression, hysteria, insomnia, liver and kidney troubles, rheumatism and skin diseases, but it was also open to healthy people.

Photography was an important tool for Pitcairn-Knowles during the time he ran the resort. He documented treatments, produced educational material and traced the history and methods of the Schroth Cure, which he published, lectured on and exhibited. Riposo eventually closed in 1962.

9. Get outside

The restorative power of nature has long been known. Whether it's a long walk beside the sea, a hike through woodland, a bracing trek across fields and mountains, or even time spent exploring a city, the great outdoors is the perfect way to unwind, get your steps in and discover new things.

10. Drink from a Lemnos clay pot

These cups were made from a special clay from the island of Lemnos in the Aegean Sea. It was thought to have health benefits, including offering protection against poison and plague. The clay was used to make drinking vessels in prehistoric times, and people even ate the clay itself.

In 1453, Lemnos was conquered by the Ottoman Empire and on 6th August each year, the Ottoman governor of the island presided over an annual ceremony to dig up the clay. It is not known whether this was a revival of the tradition from antiquity, or whether the clay had been in continuous use on the island. Because it was only excavated for six hours per year, the clay was very rare, and so vessels made from it were marked with a special seal to prove that they were genuine. The Latin word for a seal, sigillum, gave these vessels the name terra sigillata or 'sealed earth'. Wares made from this clay are also known as Terra Lemnia after the island of Lemnos.

Red clay from Lemnos was particularly prized – it was used at the Ottoman court and even shaved into the Sultan's food. Whiter clay was used to make vessels for sale in the Istanbul bazaar.

11. Purge bad 'humours'

In 1634, Welsh clergyman and astrologer, John Evans, published a pamphlet extolling his new medicinal wonder, the 'Antimonial Cup', claiming its use would, "disperseth the Dropsie; cureth the Jaundise; procureth cheerfulnesse and gladnesse of the heart", among a long list of 17th-century miracle cures. Antimony is a toxic metal that is as potent (and poisonous) as arsenic and lead. In The Universal Medicine: or The Vertues of the Antimoniall Cup, Evans advised that drinking a measure of wine that had been kept warm overnight in one of his antimony cups would, within hours, induce vomiting and diarrhoea, thus purging the body of the bad 'humours' that were thought to cause disease.