Cube Quest is a shoot ‘em up arcade game, where the player guides a spaceship through various environments, which are structured as a cube, to reach the Treasure of Mytha. While it was not a huge commercial success, it is celebrated in the gaming community due to its advanced use of computer graphics at the time.

Here is an edited extract of a conversation between Paul Allen Newell and Livia Turnbull, Assistant Curator of Design, Architecture and Digital at the V&A, in which Paul reveals how he found his way into game design and the complex process of making Cube Quest.

Livia Turnbull: I’m interested in how you got into game design in the first place? It’s obviously a field that still needs a lot of skill today, but back in the 1970s I imagine it was really hard to access that kind of training.

Paul Allen Newell: Back in 1970, I was a graduate student in film and video at UCLA. I was doing experimental video with Shirley Clarke and and computer animation with the pioneer John Whitney.

LT: What kind of equipment were you working with at that time?

PAN: The amount of equipment UCLA had for doing computer animation was almost non-existent. The film school’s animation department didn’t include computers and the Art Department only had a Tektronix 4051. It convinced me that I needed to go and find somewhere that had the facilities that I needed. Somehow or another – I can’t remember the exact way it happened – I ended up with an invite out to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab where Bob [Robert] Holtzman was leading the computer graphics lab. I convinced him to let me use his equipment there.

David Em was working there at the time as the official artist in residence – so the joke was that I was the unofficial artist in residence. I wasn’t allowed there during the day, but at night when everybody was gone, I had free use of all the equipment. At the time, Jim Blinn was working on the Voyager missions to Saturn and Jupiter.

LT: And you were still studying at the time?

PAN: Yes, I got my Master of Fine Arts (MFA). Rumour had it that it was the first computer animation film that was awarded an MFA at UCLA. The problem with it is that nobody can verify it because the professor of animation did not believe in computers and did not think it worth acknowledging.

LT: Can you tell me about that pivot to games?

PAN: I needed a job once out of graduate school and answered an ad for videogame programmers. This was a new domain so pretty much just having experience computer programming to make images, movies, interaction was enough to be considered. I got the job and started in June 1981 by programming for the original Atari 2600 VCs, and the Vectrex home units. I loved it! After doing those home game systems, I had the opportunity to do an arcade game.

LT: That was Cube Quest with Simutrek?

PAN: Yes.

LT: Am I right in thinking that was a new company when you joined? Could you tell me a bit about some of the challenges with equipment that your team faced?

PAN: When we formed Simutrek, there was nothing – we showed up in the office on the first day and we had to start from scratch, even inventing our own hardware.

We started by getting permissions from the company that made the Vectrex, that I had already programmed a game for, so we could use one of their units for development. It was a great start because it gave me a way to have a display with a system that I already knew how to programme. So I did the first iterations of the game in Vectrex. This allowed me to develop the game on existing hardware while the real arcade hardware was being created.

LT: What was the concept for that game?

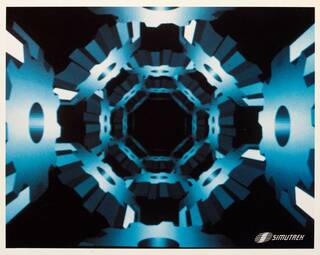

PAN: One of the defining features of the game is that the 3×3 cube consists of 54 corridors – it was modeled after a Rubik’s Cube and each of the nine planes could be rotated clockwise or counter-clockwise. For the game play, you effectively do battle in each corridor and fly down to go to the next. As the game involves surfaces which were a bit like a Rubik’s Cube, it meant it continuously changes where you’re going. Each of the corridors is unique, and we did them in different ways – the majority with computers. There are a couple that are made using traditional animation – an artist sitting down and drawing, like the one in the display.

The team was doing the background imagery with the American production company Robert Abel and Associates. It’s a lot “sexier” than the simple animation. We’re not just branching down paths, we’re using loops so you can play endless corridors – we had our own custom laser disk player that was enabling all this. So it uses a laser disk for the backgrounds, and a line buffer for the graphics, combining those two techniques.

LT: And how did the release go?

PAN: Oh, the game totally failed. Tanked. Blew up!

LT: I think you’re underselling it! Even without commercial success, it was this huge leap forward in graphics, and it’s still celebrated today as an important innovation.

PAN: Well, that’s the thing, technically it was a major increase in what arcade video games could do, up until that point it was either pixels (think Pac-Man) or you had vector (which Tempest used). That means it’s actually being generated line by line, and that’s the precursor to frame buffers in videogames.

Video of Cube Quest game play

LT: So do you have any ideas about how the two image stills from Cube Quest ended up in Patric Prince’s collection here at the V&A?

PAN: Well, I met Patric through her husband Bob Holtzman, at the time when I was using the equipment at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab. When we released the game, we had to go down and show it in New Orleans at the annual arcade show. The company made some promo material, and the two pieces you have in the collection were part of this promo material. Patric got in touch with me to ask for copies at this point – I sent them over to her as a friend.

We actually stayed in touch and ended up working together a little. When she did her 1986 SIGGRAPH art show, I was the one who put together the six-hour video retrospective for her. I was surprised to see that these stills ended up in her collection, and then at the V&A. Patric’s interest was generally more artistic, and this is a purely commercial product.

LT: That’s really interesting to hear. I think her collection is really unique in that a lot of the works have come in through her personal connections to artists.

PAN: She definitely had one-on-one personal relationships with a large number of these artists. Looking back it was really important that she collected and cared for this kind of material.

LT: Paul, thank you so much for taking the time to talk to me.