In the 16th century, portrait miniatures were painted in watercolour usually on vellum (fine animal skin). The delicate painted surfaces were protected in lockets or small boxes, meant to be worn or carried in pockets. This art form developed from the medieval art of illuminating or illustrating handwritten books, also known as ‘limning’. In the 17th century, the term 'miniature', an anglicisation of the Italian word for limning (miniatura) caught on and was used to refer to something small.

Whilst portrait miniature painting in watercolour had a long tradition in Europe from the 16th century to the 19th century, from the 1630s patrons had the additional choice of miniatures painted in enamel. The earliest known signed and dated enamel portrait was made by Henri Toutin in France but the art was popularised by his student, Jean Petitot, who worked in both French and English courts. This new style of miniature was immediately attractive to royalty and courtiers for their rich colour and durability. Unlike those painted in watercolour, which were easily damaged by fading and damp, the glass of enamel retained its colour and remained sturdy in structure.

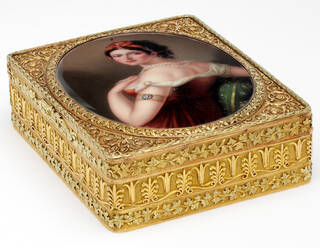

Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert first became interested in miniatures through their collection of gold boxes, some of which were set with small enamel portraits. Arthur was impressed by their vibrancy and technical achievement and often encouraged visitors to examine them through a magnifying glass to truly appreciate the tiny details and the incredible skill that it took to create them.

Painting faces with fire

There are two types of support for portrait miniatures painted in enamel: porcelain or a thin sheet of metal. Metal supports can be fired at a higher temperature than porcelain which makes the final product more resilient and scratch-proof. Enamel miniatures were first painted on gold, as the technique derived from painted enamel scenes on gold watchcases. As the technique developed, copper became used more frequently as it was cheaper and could be fired at an even higher temperature. The miniatures in the Gilbert Collection are painted on gold or copper and often decorated with gold, gemstone, or wooden frames.

To create enamel miniatures, the portraitists had to be skilled painters and able chemists. The powdered glass and metal oxides are mixed with oil to make a thin paste which is then painted colour by colour onto a metal or porcelain base. After the application of each layer of colour, the miniature is fired in a kiln.

The first layer would cover the entire support, including its reverse, to stop it from warping in the intense heat of the kiln. This reverse layer is known as 'counter enamel'. The colour which had the highest firing temperature – determined by the chemical makeup of the paint – would be applied first, and the remaining colours then applied in successive order. Before the invention of temperature-controlled kilns, the different firing heats would be achieved by time – around 15 minutes for the highest temperature and as little as two minutes for the lowest. Each firing introduced the risk of ruining the picture if the enamels composition and the firing temperature were not perfectly controlled. This meant that the creation of a painted enamel had to be meticulously planned, as each colour only had one chance to be fired.

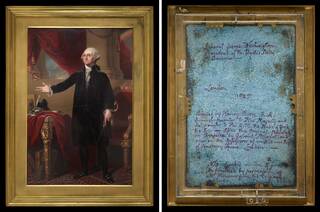

The larger the metal base, the greater the risk of the enamel warping and cracking. Henry Bone pioneered the large format miniature in the early 19th century. From the 1780s, Bone made a series of innovations, including enamel paint compositions with lower firing temperatures, allowing him to create increasingly larger enamel paintings. His 1825 painting of George Washington, measuring approximately 30cm by 20cm, bears the scars of this process through a large crack that runs horizontally across the president's chest. However, Bone's patron, a Mr Williams, still admired the piece and allowed Bone to finish it. The reverse is inscribed with ‘Cracked in the 5th fire & finished by the permission of Mr. Williams from the Original picture’. You can find this portrait displayed from the reverse, where the inscription and crack are visible, in the Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Galleries room 71.

Well-known techniques regularly used in enamel portrait painting include 'stippling' and 'sgraffito'. Both are painting techniques adopted to introduce new textures for a more realistic effect. Stippling requires a number of small individual dots, applied using a fine brush. This is often used to create a subtle gradient in colour. Sgraffito uses a pointed wooden stick tool to scratch out lines whilst the enamel is still wet. Sometimes this is employed to create hair lines or details on clothing.

Large scale to small scale

Large oil paintings formed an integral part of the interior decoration of country houses. Portrait miniatures, by contrast, were small and portable and could even be worn as part of a bracelet or tied to clothing with ribbon.

Some enamel miniatures, however, took inspiration from large-scale oil paintings. The miniature of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, dated 1779, took her portrait from a family depiction with her two siblings which hung in her childhood home. The family portrait was painted in 1774, the same year that Georgiana married the 5th Duke of Devonshire. The artist, Angelica Kauffmann, painted Georgiana and her siblings in a fashionable landscape setting.

In the enamel miniature of Georgiana, only her head and shoulders are presented, making the image more personal. A large-scale painting displayed on a wall has become a small-scale portrait held in one’s hand, and the experience of looking at a formal painting of a group has become an intimate encounter between the viewer and the sitter.

The enameller, Johann Heinrich Hurter, was particularly well known for reproducing large oil paintings in small scale enamel paintings. The other examples in the Gilbert Collection include a portrait of Queen Charlotte, after Thomas Gainsborough, and a portrait of King Charles I, after Van Dyck.

Whilst many enamel miniatures were often copied from engravings or paintings, reproducing famous or favourite likenesses, some experienced enamellers prided themselves on being able to paint directly from their subject as a demonstration of their technical mastery. Some works signed 'ad vivum', meaning 'from life', confirmed this classification, but others, such as this one by Jean Baptiste Weyler, have since been described as made 'from life' by art historians impressed with their lively style.

Close connections

Painted enamel likenesses of loved ones were treasured possessions which celebrated personal connections. For the gentry and aristocracy, they could also be an eloquent way to express their social status. The miniature of Anne Churchill is engraved with her familial connections – as the daughter of the 1st Duke of Marlborough, wife of the 3rd Earl of Sunderland and mother of the 2nd Duke of Marlborough. The enamel, set in its engraved case, has become a memorial to Anne and her important role in securing for her husband's family the Dukedom of Marlborough, transferred from her father to her son.

Miniatures were also used to remember lost family members. A mourning slide in the collection has two loops at the top and bottom of the reverse allowing for a ribbon to thread through and be tied to a wrist. Miniatures of mourning were sometimes made as slides so the wearer could secure it tight to their skin. The slide includes a decorative inscription on the counter enamel, 'Les morts y sont vivants' meaning ‘The dead are alive there’. The intimacy of mourning is further accentuated by the small size of the miniature, measuring approximately 3cm by 2cm, which keeps the personal accessory easily concealable.

Inscriptions on the reverse or inside cases often included memorial poems, words of comfort, or the details of the sitter. Other ways of remembering a loved one were to include locks of hair, styled or braided, kept inside a locket or presented at the back of enamel miniature cases.

Portraits as presents

Enamel miniature portraits were initially popular as diplomatic presents, given by rulers to their subjects or to essential allies. From the 1660s, such presents were framed with diamonds and called 'boîte à portrait', French for 'box with a portrait', derived from the leather box in which they were presented. As diamonds were frequently dismantled and sold, this example, with its original setting, is an extremely rare survivor. It depicts an Elector – a German prince entitled to take part in the most prestigious election of the Holy Roman Emperor, the largest empire in Western Europe at the time.

The potential for secrecy made miniatures the perfect gift for a lover, allowing them to keep their beloved physically close but hidden, to contemplate their face in private. Miniatures were also given to celebrate more legitimate unions and were popular as wedding gifts, particularly in the 18th century when wives often wore their husband's image as part of a bracelet or necklace.

This pair of portraits of a newlywed couple would have originally been set in a pendant or bracelet so that they could have been worn. Their later frames would have been added to make them easier to display in a cabinet, or on a wall.

Famous faces

As these personal images changed hands and entered art collections, new owners often reframed and hung them on walls or in cabinets. In the process, the identity of the people depicted and the nature of the affection they once shared with the original owner often became lost. Some artists, including Swedish enameller Christian Friedrich Zincke, produced such a high volume of commissions and often used the same studio accessories, which makes it hard to identify individuals by their clothing.

Despite this, many sitters of miniatures are easily identifiable for their depictions of famous – or even infamous – individuals. Horace Walpole, a renowned 18th-century collector, had a special cabinet made to house his miniatures. In it, alongside antique cameos and relics, he kept a collection of just under 100 miniatures, selected not only for their beauty but often for the fame of their subject. Walpole's collection of famous faces acted as illustrious company for the portraits of himself and his family, including his father, Prime Minister Robert Walpole. They were also a way for Walpole to spend time with those historical figures who fascinated him as collector, in much the same way they fascinated the Gilberts.

In the Gilbert Collection

Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert were both equally fascinated by the famous faces of history. They amassed miniatures in the same way and for the same reasons that generations of collectors had before them. Visitors to the Gilberts' Beverly Hills home, upon viewing their collection of enamel portrait miniatures, could appreciate not only the history of this art form and the famous faces captured by it but also Rosalinde and Arthur's grasp of the subject. Bringing together characters from history, rendered by the best artists, their collection of enamel miniatures made both their knowledge and good taste visible.

Discover more of The Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection.

Explore the V&A's collection of portrait miniatures.