The V&A collection includes four photographs from her series Hyenas of the Battlefield, Machines in the Garden (2015), which examines how immersive technologies — used for military training and post-traumatic stress disorder treatment (PTSD) — blur the lines between fiction and reality, challenging traditional notions of photographic truth.

Clara Bolin, Curatorial Fellow Museum Curator for Photography, supported by The Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach-Foundation, interviewed Lisa Barnard to find out more about the Virtual Iraq and Whiplash Transition projects that form her series Hyenas of the Battlefield, Machines in the Garden.

Clara Bolin (CB): Your photograph Interrogation Set 2015 is part of the FlatWorld Immersive system at the Institute of Creative Technologies in Los Angeles. It features a set which is designed to look like a military interrogation room and is propped with distinctly Middle Eastern furnishings. It is described as an ‘immersive system’ that simulates conflict environments. How does this form of immersion work and who is it intended for?

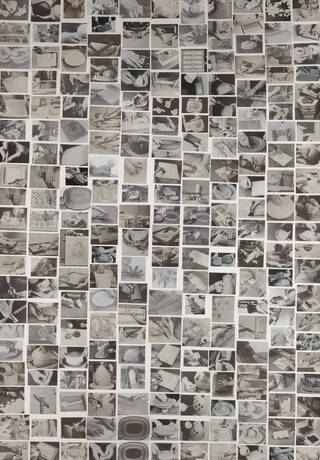

Lisa Barnard (LB): The images at the V&A are from the Virtual Iraq project, 2008. This is part of a mixed reality, training set for a soldier who is about to set off on a tour of duty, preparing them for what they might expect. The idea is to provide the soldiers with an environment that is as ‘real’ as possible, using technologies that they are familiar with, such as those aligned with the gaming industry. The combination of technology and real objects can aid the sense of immersion and help familiarise the space that they might be working in, such as a house in Fallujah, Iraq. Virtual reality programmes at the time were also being used to treat soldiers with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or to train them in interrogation techniques and how to respond in conflict zones. The soldier uses a statistical analyser programme to ask a potential terrorist, Raed Mutaz, if he planted an explosive device. I was interested in the topic of PTSD for personal family reasons, as my grandfather served in both the First and Second World Wars and ended his own life due to PTSD when he was already quite old.

(CB): I’m interested in the role that images of war play in different contexts. Through the digital images integrated into the room, the screens come to play an important role. How does this influence the relationship between trauma and the representation of war?

(LB): Yes, this is what was fascinating for me as well, that an image of a market in Iraq can be at once both informative and traumatic. Understanding your symptoms of PTSD means that you must know what your ‘triggers’ are, what visions or images cause you to become anxious, panicky and at its very worst, extremely distressed. The trauma theorist Cathy Caruth writes about post-traumatic stress and trauma in relation to images and other perceptive modalities. The traumatic event can be re-imagined as if it were real, through seeing, smelling, hearing – anything that reminds you of the event, re-traumatising you again and again. It doesn’t matter if the event that is being repeated is true or not, the issue is that you are controlled by it and in a constant state of fear.

The Institute of Creative Technologies created the Virtual Iraq virtual reality programme to address directly PTSD for the military, because of the high rates of suicide after periods of intense conflict. Much like exposure therapy, the screen can be used to help you assimilate the event, building the image of it slowly so that you are no longer afraid of it (much like moving closer and closer to a spider, for example, over a period of time so that eventually you can hold one in your hand). This happens in real time with a psychologist to support the process so that the event becomes less terrifying.

(CB): Since its introduction in the 19th century, the medium of photography has been linked with the idea of recording ‘the truth’. Being described as a device of mechanical objectivity, a photo has historically functioned as a token of what is in front of the camera. In your work, simulation, immersion and reality merge. What implications does that have for our understanding of truth?

(LB): I have always been interested in the idea of objective truth and the image. The notion of ‘truth’ in photography is of course very important within documentary practices, particularly work that is visually explicit. In terms of aesthetics, it’s the least interesting aspect of photography for me. I am more interested in photography that you have to work a little harder at, uncover hidden meanings, and as part of broader and more complex perceptual experience, emotion etc. This complexity, where the personal and the real merge makes photography more truthful.

(CB): In a post-truth age and with the rise of fake news, what impact do computer-generated images have on our understanding of photography and its relation to reality?

(LB): Sometimes truth needs fiction to be realised – one needs to stage life to really grasp it. We are surrounded by familiar images, particularly of conflict, and the people suffering under systems of control. These images support the colonial, traditional ideas of ‘othering’, with the photographer in the position of power and the subject powerless.

Fictionalised stages, such as computer-generated imagery, generally rely on additional contextual information to help the process of immersion in the narrative being told, whether that be text, other media and now artificial intelligence. It’s important to use the right tool to tell the story, in the best way. They are also much more subjective – the artist becomes the narrator and makes that explicit. Photography within this mix of media is far more interesting, being less indicative and less reliant on the ‘it’s enough just being there’ mentality.

(CB): In 2015, you published a book with the title Hyenas of the Battlefield, Machines in the Garden. Who are the ‘Hyenas’ and what are the ‘Machines’?

(LB): ‘Hyenas’, according to the German author Bertolt Brecht, are individuals who benefit from war, such as Mother Courage in his play Mother Courage and her Children (1941), where she profits from soldiers by selling them goods. ‘Hyenas of the Battlefield’ is a phrase that I developed when thinking about the huge corporations that profit directly from the production of machinery used in the theatre of war – those connected to the military-industrial complex.

The Machine in the Garden (1964) is a book written by Leo Marx, which discusses the tension between the pastoral ideal in North America during the 19th century and the intrusion of technology. I suppose it was a time when machines started to become ubiquitous in homes as time-saving devices, and we started to rely on them.

(CB): The images in our collection are all related to your work in the United States, but another series in the book, the Whiplash Transition project, expands the geographical range to Pakistan. How do they relate to the broader themes of the project?

(LB): The Whiplash Transition project was created three years after the Virtual Iraq project. Much like the Virtual Iraq project, Whiplash Transition also had PTSD as a starting point but shifted the focus from soldiers to drone pilots. At the time, drones were part of a new paradigm introduced by George. W Bush and then expanded by Barack Obama, to take all American Soldiers out of the theatre of war. Subsequently drone pilots became responsible for killings with dreadful cases of ‘collateral damage’, women and children – the innocent suffering most, as they always do in war zones. The screen was problematic for drone pilots when operating remotely in conflict zones. This was mostly due to their prolonged visual exposure to the scenes – virtually remaining at the scene of horrific events that had occurred under their supervision. I broadened the work out to explore the relationship of the screen to conflict in general – how it’s used in culture and the connection to the military-industrial complex.

The difference with the Whiplash Transition project is that the drone pilots, who operated out of Las Vegas and flew drones into Waziristan in Pakistan, for example, experienced their trauma directly via the screen, through the drone’s video feeds as they released a missile that destroyed human life. What the military found was that drone pilots were experiencing very high rates of PTSD, despite their physical distance from the battlefield. But let's not forget that this is nothing compared to what those on the ground were experiencing, with the constant humming of drones overhead and the threat of death by hellfire missiles. War is appalling and suffering is greatest for those with no power and no voice to change anything or bring conflict to an end.

'Interrogation Set, Part of the FlatWorld Immersive system based in Los Angeles, 2015', is on display in American Photographs, Rooms 100 and 101 until 16 May 2027.