Originating in the 16th century, the earliest wallpapers were used to decorate the insides of cupboards and smaller rooms in merchants' houses rather than the grand houses of the aristocracy. But by the beginning of the 20th century, it was being used everywhere, in hallways, kitchens, bathrooms, and bedrooms as well as reception rooms, and was popular in both the wealthiest and poorest homes. Yet, it was this very popularity that led to wallpaper being regarded as the poor relation of the decorative arts.

Take a journey through the V&A's vast wallpaper collection, dating from the mid-1500s to the present day, to discover its fascinating design history.

How was wallpaper made?

Many early wallpapers featured stylised floral motifs and simple pictorial scenes copied from contemporary embroideries and other textiles. They were printed in monochrome, in black ink on small sheets of paper that measured approximately 40 cm high by 50 cm wide. It was not until the mid-17th century that the single sheets were joined together to form long rolls, a development that also encouraged the production of larger repeats and the introduction of block-printing, which continued to be used in the manufacture of more expensive wallpapers until the mid-20th century. In this process, the design was engraved onto the surface of a rectangular wooden block. Then the block was inked with paint and placed face down on the paper for printing. Polychrome patterns required the use of several blocks – one for every colour. Each colour was printed separately along the length of the roll, which was then hung up to dry before the next colour could be applied. 'Pitch' pins on the corners of the blocks helped the printer to line up the design. The process was laborious and required considerable skill.

In a process that can take up to 4 weeks, using 30 different blocks and 15 separate colours, this video recreates the painstaking process in block-printing a William Morris wallpaper design from 1874.

This video has no sound.

Taxing times

Technical improvements in the block-printing process meant that by the middle of the 18th century patterns could be printed in many colours and styles and the wallpaper industry in Britain flourished. As a result, it attracted the attention of the Excise Office who saw in wallpaper a potentially rich new source of revenue. A tax of 1d (0.75p) per yard was levied in 1712, rising to 1.5d (1p) in 1714 and 1.75d (1.25p) in 1777. These taxes inevitably led to increased prices and encouraged manufacturers to focus on more expensive wallpapers. Despite this, demand remained high and elegantly coloured patterns were sold by fashionable upholsterers like Thomas Chippendale.

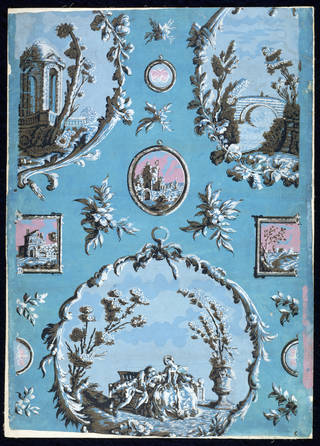

The period was also particularly rich and inventive in terms of design. Floral patterns containing finely-coloured roses and carnations were most popular but architectural and landscape scenes were also admired. A paper from Doddington Hall contains framed figures and landscapes interspersed with flowers and insects, and the bright blues and pinks remind us that 18th-century interiors were often decorated in vivid colours. The idea of a wallpaper incorporating pictures within frames was inspired by the fashion for rooms decorated with prints cut out and pasted directly on to the wall, known as Print Rooms, that were pioneered by collectors such as Horace Walpole.

Flocks

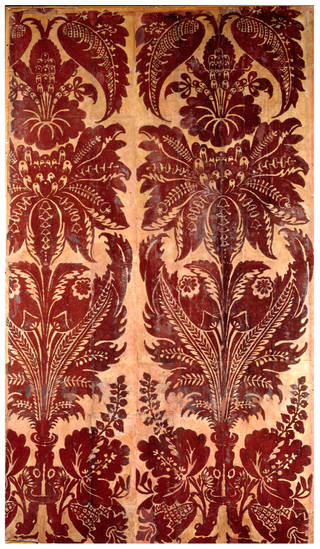

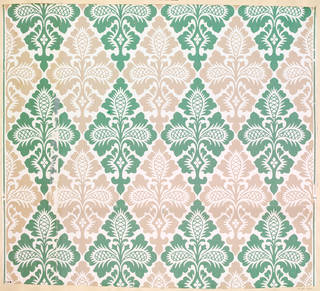

Most flock patterns were copied from textiles and imitated the appearance of cut velvets and silk damasks. Flock wallpapers were made with powdered wool, a waste product of the woollen industry, which was shaken over a fabric prepared with a design printed in varnish or size (a substance similar to glue). The powdered wool formed a rich pile that stuck to those areas covered by the design. At first, flock was applied to canvas or linen, but in 1634 Jerome Lanier, a Huguenot refugee working in London, patented a method by which the coloured wools could be applied to painted paper, and by the end of the 17th century flock wallpapers, as we know them, had appeared. They quickly became extremely fashionable. Their ability to accurately imitate textiles, at a time when it was customary to cover walls with fabric, was greatly admired, as was their cheaper price. Flock papers also had the added advantage of repelling moths due to turpentine used in the adhesive. A particularly magnificent example, featuring a large damask design of crimson flock on a deep pink background, was hung in the Privy Council offices, Whitehall, around 1735, and in the Queen's Drawing Room in Hampton Court Palace. By the third quarter of the 18th century there was hardly a country house in England that did not have at least one room decorated in a similar fashion.

Chinese wallpapers

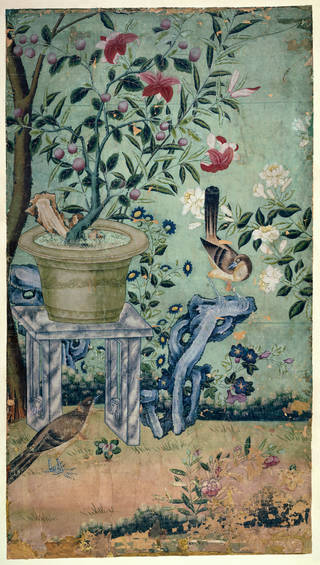

An even more expensive decoration were the wallpapers made in China that first appeared in London in the late 17th century as part of a larger trade in Chinese lacquer, porcelain and silks. They rapidly came to dominate the market for luxury wall coverings for the next hundred years. Unlike European wallpapers, Chinese papers were painted, not printed, and featured large-scale, non-repeating pictorial scenes. Every set of papers was individually composed but the designs tended to fall into two groups. The first depicted the occupations and activities of Chinese life, while the second represented an assortment of exotic plants and birds, elegantly balanced in a landscape of shrubs and trees, that covered the walls of an entire room. Ironically, the Chinese did not use wallpapers themselves and their products were made exclusively for export. The accuracy and sophistication of their colours, and the naturalism and detail of their designs set new standards of excellence in wallpaper manufacture and established it as a luxury decoration much sought after. However, such was their reputation that before long European manufacturers were producing printed and hand-coloured imitations.

Mass-production

Up until 1840 all wallpapers were produced by hand using the block-printing process that, as we have seen, was labour-intensive and slow. Not surprisingly, manufacturers were keen to find ways of speeding up production and in 1839 the first wallpaper printing machine was patented by Potters & Ross, a cotton printing firm based in Darwen, Lancashire. Adapting the methods used in the printing of calico (a plain-woven textile made from cotton), the paper passed over the surface of a large cylindrical drum and received an impression of the pattern from a number of rollers arranged around its base. These were simultaneously inked with colours held in troughs beneath each one. The first machine-printed papers appeared thin and colourless beside the richer and more complex effects of block-printing and most had simple floral and geometric designs with small repeats. But no-one could deny the speed and economy with which wallpaper could now be made. Production in Britain rose from around one million rolls in 1834 to nearly nine million rolls in 1860, while prices dropped to as little as a farthing a yard (0.25p). In the space of just one generation wallpaper had become a commodity available to all but the most poor.

Design reform

Mid-19th century wallpapers encompassed a huge variety of designs, including marble and wood-grain effects, imitation stucco, textile patterns, historical pastiches and revivalist styles. The most common were the many thousands of patterns featuring floral motifs and papers printed in bright colours with realistically shaded cabbage roses. To our eyes the naturalism of these patterns is quite appealing but to critics like the architect A. W. N. Pugin, it was characteristic of all that was wrong in Victorian design. Naturalistic patterns, he argued, were not only objectionable on aesthetic grounds but also inappropriate for the decoration of a wall. Their three-dimensionality did not work with its flat and solid surface and produced a disturbing and dishonest impression of depth. In their place, Pugin advocated designs with conventional ornament rather than realistic motifs. His own wallpapers contained his favourite medieval and heraldic ornament, but other designers like Owen Jones stylized nature, reducing flowers and foliage to a series of formal, symmetrical shapes. Despite the wide publicity given to these views, they never really took hold outside the design establishment and both manufacturers and the majority of their customers continued to prefer more traditional and naturalistic styles.

William Morris

The writer, designer, conservationist and socialist, William Morris is possibly best-known for his wallpaper designs. He was responsible for more than 50 patterns and his influence upon the industry was long-lasting and profound. His work represents something of a compromise between the conflicting styles of the 1850s and 1860s. It has neither the full-blown, three-dimensionality of the mid-century cabbage rose, nor the geometrical severity of reformers' designs. Whereas Pugin and others abstracted nature according to a formulaic set of rules derived from historical example, Morris' abstraction of natural forms stemmed from direct observation of their organic shapes and curves. Also, in place of the exotic blooms, favoured by commercial manufacturers, most of Morris' patterns used commonplace plants that grew wild in meadows and the countryside. One of his most popular designs, Trellis (1864), was inspired by the rose trellises at Red House, his first home, and Willow Bough (1885) was based on drawings of willow branches that he made at his country home, Kelmscott Manor. The enduring impact of Morris' work can be seen not only in the many Arts and Crafts' imitations of his stylised natural forms, but also in the way that he transformed attitudes to decoration, encouraging a generation of middle-class consumers to want art and beauty in their homes.

A proliferation of pattern

The frieze-filling-dado wallpaper scheme highlights the popularity of wallpaper in Victorian homes. It was first recommended in 1868 as a way of breaking up the monotony of a single pattern on the wall, and by 1880 it was a standard feature in many fashionable interiors. The dado paper covered the lower part of the wall, between the skirting board and chair rail; above this hung the filling, and above this the frieze. And as if three different wallpapers were not enough decoration for any room, the scheme was often combined with ceiling papers to complete the densely-patterned effects. Ideally, the frieze should be light and lively, the filling, a retiring, all-over pattern, and the dado should be darker to withstand dirt and wear and tear. Co-ordinating papers, printed in muted 'art' greens, reds, yellows and golds, could be extremely attractive but the frieze-filling-dado-ceiling combination often led to visual overload. The treatment was best suited to hallways and stairs. But by 1900 ceiling papers had disappeared and, in artistic interiors, wide friezes, like the Peacock pattern produced by Shand Kydd, were hung above plain or simple panelled walls.

Nursery wallpapers

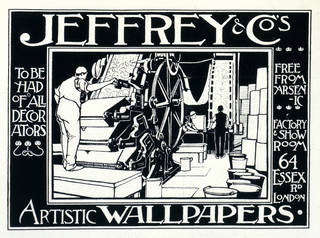

As the market for wallpaper expanded, increasingly specialised products were designed for ever-more specific functions and rooms. Victorian children were thought to be uniquely sensitive to their surroundings and by the last quarter of the 19th century many manufacturers were producing nursery papers aimed at improving impressionable young minds. The artist and illustrator Walter Crane, who was a prolific designer of wallpapers, was a master of this genre and his Sleeping Beauty (1879) paper exemplified the qualities of beauty and moral instruction that were required. The delicately drawn, slumbering figures entangled in a rose were clearly artistic, while the subject was well suited to encouraging children to sleep. Also, the wallpaper was especially practical. The oil-based pigments meant that it could be washed – or at least sponged – without damaging the colours. And even more importantly, it was arsenic-free. Arsenic had been widely used in the production of paints, fabrics and wallpapers since the 1800s and by the 1870s it was thought that the vapour given off by damp wallpapers could cause illness and even death. Children and the sick were particularly vulnerable. Growing public anxiety about the dangers of these wallpapers led manufacturers to develop products that were free of poisonous substances. Sleeping Beauty was included in a range produced by Jeffrey & Co. in the mid-1880s, entitled Patent Hygienic Wallpapers, that were advertised as washable and arsenic-free.

From jazz to pop

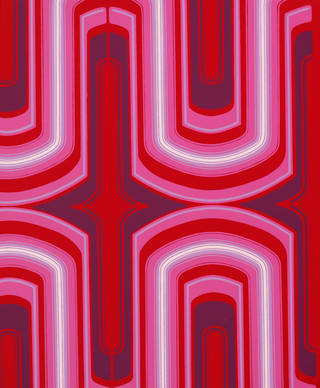

The 1920s and 1930s were boom years for the wallpaper industry in Britain and production rose from 50 million rolls in 1900 to nearly 100 million rolls in 1939, with most of the activity concentrated at the cheaper end of the market. While traditional stylised leaf and flower patterns continued to be widespread, patterns influenced by modern art and popular culture also appeared. Brightly-coloured, zig-zag, jazz designs vied with Cubist-style motifs in more design-conscious homes while Oriental subjects proved popular with customers seeking novelty. Arabian themes were inspired by the success of films like The Sheik (1922); Chinese patterns were indebted to books like Sax Rohmer's Fu Manchu series; and the discovery of Tutankhamen's tomb in 1922 led to a brief craze for Egyptian motifs. Cut-out borders and decorative panels, featuring geometric or floral patterns were combined with lightly embossed, plain or semi-plain backgrounds. The 'Good Design' movement of the 1950s favoured less fussy effects. It encouraged the use of flat, linear patterns and abstract geometric motifs, only to see them replaced by an explosion of bright colour and hallucinogenic Op and Pop designs in the 1960s. New products and new processes coincided with the growth of do-it-yourself (DIY) and in 1961 the first pre-trimmed and ready-pasted papers appeared, quickly followed by laminated papers, metallic finishes, and then tough, scrubbable vinyl wallpapers.

Wallpaper now

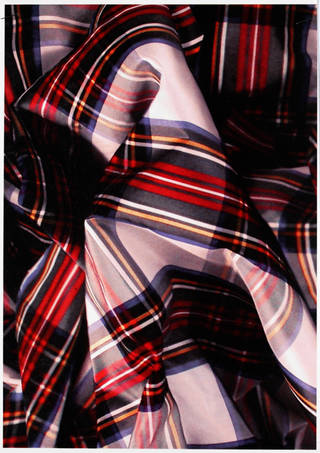

The 1960s and 1970s represented a high point for many wallpaper manufacturers when sales were strong and designs were bold and modern. But the oil crisis of 1973 led to a significant reduction in the size of the industry world-wide, with many firms going out of business or being taken over by large international corporations. Increasing competition from the paint industry and the popularity of finishes like stippling (creating shapes and images by making many small dots) and rag-rolling (using a roughly folded cloth to create a marbled effect) in the 1980s also led to reductions in sales and the only areas of growth were in the cheaper, mass-produced goods sold in DIY superstores. More recently, however, wallpaper has undergone a revival in its fortunes. The fashion for feature walls has encouraged a taste for larger, more assertive patterns while the development of digital printing and the revival of screen-printing has enabled artists and freelance designers to get involved. Deborah Bowness and Tracy Kendall make bespoke and limited edition papers that are more like installations than wallpapers. Firms like the Glasgow-based Timorous Beasties transform traditional pastoral scenes into dark, edgy images of contemporary life, and the involvement of big names from the world of fashion, such as Vivienne Westwood and Ralph Lauren, has helped to make wallpaper the essential background for a bold 21st-century lifestyle.